Materially Immaterial: Perspective and Value Creation through NFTs and Photographic Negatives

Written by Makenna Woodward-Crackower

Edited by Paige Suhl

Figure 1.

Mitchell F. Chan, Digital Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility (Series 0, Edition 10), 2017, NFT, hosted at Natively Digital 1.2, Sotheby’s Metaverse.

Figure 2.

William Henry Fox Talbot, The Ancient Vestry, Calvert Jones in the Cloisters at Lacock Abbey, c. 1845, Paper Calotype Negative, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Preface

Above is a blank computer screen. Below is a blank piece of paper. You might be surprised to learn that the above is currently valued at $1.5 million, and the below is in the Victoria and Albert museum under lock and key, and is quote “not available for issue to the public... due to light sensitivity”.1 Both are considered and valued as works of art. Why and how this could be true, shall be the subject of this essay.

Introduction

The world is indeed shrinking. In some ways, the advent of the digital age is the natural conclusion of over five hundred years of colonial imperialism, and its successor, industrialism. Throughout this period, crises of cultural ownership and artistic ontology have been representative of underlying sociological and economic paradigm shifts. The relative newness of NFTs on the art market has caused some to celebrate a radical renovation of understandings of art and value, while others have lamented the strange detached-ness of this confusing and impersonal technology.2 NFTs are not a new concept, but rather a maturation of the “problematics” of art in the digital age. The creation of NFTs and NFT trading platforms are an apparatus that is indicative of these recurring themes in global art history. In order to illustrate what I mean, I will examine the invention of photography and the similar way in which it disrupted its contemporaries.

I am trying to reconcile the fact that we are undergoing a similarly radical shift in our understanding of art to that which was experienced in the mid-nineteenth-century through the invention of photography. The act of securing light on paper has echoes in today’s attempts at securitizing ownership of digital art through the blockchain. In terms of codifying authenticity, I believe that the photographic negative instigated by William Henry Fox Talbot’s creation of the calotype method has similarities with the NFTs in blockchain technologies. My paper will be divided into three achronological periods, and I will attempt to mark clearly where they meet, mainly through Walter Benjamin’s conception of the “Aura”. My argument being that, the negative of a photograph operates in the same way as the string of code in an NFT. Both have been conceptualized as windows or portals, for the consumer/viewer to touch an idea or piece of history.

In October of 2021, Sotheby’s launched its NFT platform, entitled “MetaVerse”. They kickstarted the platform with an auction called “Natively Digital 1.2”, featuring works from the caches of NFT collectors like Paris Hilton and Qinwen Wang, among a plethora of other collectors hidden behind pixelated profile pictures and meme-worthy usernames. The auction house’s move to open up this new platform demonstrates an underlying force driving the confusing rise of the NFT market: the desire of the mainstream art market to solidify the meaning of ownership of digital content, which until this point, has been a controversial and difficult task. Sotheby’s was established in 1744 when the international art market was starting to find its footing. The auction house is representative of the ‘old-world’ art market, and their choice to become involved in NFT sales is a shocking and unprecedented move, demonstrating that NFTs, despite their apparent weirdness, are fundamentally changing what the art market will look like in the future. The auction, whose marketing strategy relied on the reputation of these enigmatic collectors, was the first of its kind by a blue-chip auction house. NFTs have garnered a sort of notoriety, which content creators and news agencies from all corners of the internet have capitalized on. Precisely what an NFT is, relies on the evolving understanding of ‘authenticity’ that has been central to the art market since its inception.

What is an NFT?

This complex digital component of the art market can often feel like a fringe movement, only available to the wealthiest connoisseurs. It also, via its crypto logic, makes the understandings of NFTs nearly inaccessible to the average consumer. Therefore, before diving into how NFTs work in relation to ownership, I must explain their ontological status. Understanding fungibility is essential to understanding this type of blockchain technology. Fungibility is the quality of a product or good that can be traded with another identical good, for the same exchange value.

For instance, one copy of a mass-produced paperback novel at Indigo is going to be worth exactly the same amount as another copy in another Indigo, given that they are the same in quality and have not been used (which would then decrease their value). Once one copy is signed by the author, however, that copy is given a special quality, despite the written content of the novel being exactly the same as every other of its type. Imagine this signed copy as an NFT. NFT stands for ‘Non-Fungible Token,’ which essentially translates its lack of exchange value. It is one of a kind, and its economic value might increase by double or more, depending on a given context. It is the signature of the artist or author who minted the NFT, which adds this special quality to the digital content.

Applying this logic to the digital realm has historically been impossible. Of course, digital work is often subject to copyright in its capacity for sale and resale, but that does not mean that the artwork cannot be screenshotted or downloaded on anyone’s computer. Digital image storage has, pretty much since the internet came about in the 90s, been widely accessible. For the average person with a computer, this is a good thing. However, many NFT advocates state that because of this accessibility, digital art loses its profitability.3 This decouples digital artists from their art’s true value and deprives them of making an income on their art, which equally-talented traditional artists working with physical media like paint and clay can make from gallery sales or auctions. According to the Harvard Business Review, NFTs make “buying and selling products that could never be sold before, or enabling transactions to happen in innovative ways that are more efficient and valuable”.4 NFTs are effectively attaching that value-signal inherent in traditional art to a digital space which exists only in code.

Another quality of the NFT is that it relies on blockchain technology. The first and foremost platform to host NFT is the Ethereum blockchain, which differs from other types like Bitcoin, in that it can embed this non-fungible quality into a token. One bitcoin token, for example, is worth the same as any other. The monitored existence of the NFT is hosted on a network of servers that are constantly running and open to anyone, which maintains that the NFT trade value is constantly publicly viewable.5 Despite not having any art purchasing power of my own, I can be made privy to the sale prices of every single NFT, including the case study I will soon mention. This documentation is hosted on servers like OpenSea.6 It also tells you who purchased it, and when. Albeit, many NFT collectors are hidden behind screen names. Despite the fact that many NFTs, like most of the contemporary art market, are only available for purchase to the uber-wealthy, they disentangle certain elements of secrecy from art market logistics. All NFT blockchain exchanges are publicly viewable, whereas the sale price of art traded at auction is frequently confidential. The fact that Sotheby’s is now taking part in this NFT frenzy might be responsive to a trend in the art market that is worrying its traditional stakeholders. In the introduction to DeLoitte’s 2019 Art & Finance report, it states that:

“Challenges regarding the valuation of art and collectibles, coupled with the perceived threat of price manipulation, have been highlighted as key areas of concern by the majority of the stakeholders in the art and finance industry...The findings from this year’s survey also show that there is a significant lack of trust when it comes to art market data. This is a serious problem, as decision-making tools for valuation and risk models depend heavily on this data and the trust we place in it. Blockchain technology and the creation of data provenance models might help in this regard.”7

To art sellers, the waning trust in the market paired with highlighted instances of corruption pose a serious threat to their business. They hope that by opening up sale records through verifiable, public means, trust will be re-established. According to Rachel O’Dwyer, one of the few academics of visual culture studying the NFT phenomenon, "value accrues less from how much the asset is actually worth and more from the information and confidence that circulates around the good”.8

Digital Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility

The lot sold at the “Natively Digital 2.1” auction which best captures the logic of NFTs is “Digital Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility (series 0, edition 10)”, by Mitchell F. Chan. Chan is a digital, sculptural, and installation artist who examines notions of space, physicality, and ownership in his work. “Digital Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility”, first minted as an NFT in 2017 at Toronto’s Interaccess, references Yves Klein’s 1958 Paris exhibition of invisible artwork titled the same (minus the “digital”, of course). It is one of the first works to be intended and created as an NFT—not originally a digital artwork or other byte of digital media subsequently minted into an NFT.

Figure 3.

Mitchell F. Chan, Digital Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility (Series 0, Edition 10), 2017, NFT, hosted at Natively Digital 1.2, Sotheby’s Metaverse.

Figure 4.

Yves Klein, Untitled Blue Monochrome (IKB 100), 1956, Dry pigment and synthetic resin on gauze mounted on panel, 31 x 22 inch, Estate of Yves Klein.

Figure 5.

“View of Yves Klein’s exhibition “The Void”, at Galerie Iris Clert, 1958”, Photograph, Galerie Iris Clert, Paris, France, The Estate of Yves Klein.

Figure 6.

Giancarlo Botti, Transfer of a "Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility" to Michael Blankfort, Pont au Double, Paris, February 10th 1962, photograph, Estate of Yves Klein.

On the Sotheby’s display page, a picture of a certificate is displayed. The bottom right-hand corner of Chan’s certificate reads “This is a certified IKB wrapper. Unwrapped IKB has no display value.” (fig. 3) IKB is Chan’s code referencing “International Klein Blue”.

Yves Klein was a French conceptual artist whose short career played on themes of self and spirit. He is most well-known for patenting a shade of blue which came to be known as International Klein Blue (fig. 4). It is a deep ultramarine colour, which, according to author Rebecca Solnit, “represents the spirit, the sky, and water, the immaterial and the remote, so that however tactile and close-up it is, it is always about distance and disembodiment”.10

At Klein’s 1958 exhibition entitled “the Void”, visitors entered a room that was entirely empty, with white walls and bare flooring (fig. 5). Not a single physical artwork was exhibited. Klein allowed exhibition viewers to purchase the “immaterial” artworks. He actually sold two of these immaterial artworks, which had to be paid for in gold in exchange for a receipt of the purchase—the only formalized existence of the work. The payment would then be thrown into a river, in a sort of performance in and of itself (fig. 6). Interestingly, this had to be done within the presence of some sort of art-industry expert, to authenticate the transaction. Then, the receipt would be burned.11 By destroying the material representation of the transaction, the artwork was assumed to be completely removed from possession by any one person.

According to Chan, “Klein came to the conclusion that “Solving the problematics of art” meant transcending the practical and sensorial limitations of the physical form. Creating a “pure visuality” meant creating works without any visual aspect.”12 When owners of various editions of Digital Zones access the digital asset they purchased, they are presented with a blank webpage screen—note the memo: “no display value” (fig. 1). Chan writes in his attached 33-page statement that “This webpage is impregnated by the artist with the pictorial sensibility of the colour blue. This creative act transcends the coding of any visual features or colour information. It is through the sheer creative will of the artist that the virtual space transmits a visual experience.”13 IKB can therefore be seen as a cumulative interrogation of traditional understandings of art and value. It links an exhibition from sixty years ago to our contemporary ontological crisis of the digital age.

I would like to push back slightly on Klein’s avowal of a complete removal from the material in his works. Although the certificate was destroyed, the evidence of the transaction was not. He documented his work and transactions through photographs (figs. 4 and 6). This reinforces my point that photography has always negotiated itself into our desire to document—the photographic image is the residual touch with that which was. Even the most conceptual art continually falls back on this process of touch, of referent and index. Now photos of Klein’s process are their own material objects, imbued with the value of having witnessed his works of nothingness in the flesh.

Digital Zones: Crisis and Consumption

Art straddles the line between commodity and cultural object. Despite the ritual placement of art in the cultural psyche, it has always been tied to its reliance on wealth; artists accrue their means of living from the discerning pockets of wealthy clients and patrons.14 The value of any single artwork is determined, therefore, wholly by the social perspective of that piece in a cultural context. Art’s monetary value is completely social because people decide if it is valuable or not. When the wealthy sit down to trade money for art and vice versa, they must agree on a specified exchange value.

Money is defined as “any generally accepted medium of exchange which enables a society to trade goods without the need for barter; any objects or tokens regarded as a store of value and used as a medium of exchange.”15 Medium thus becomes a foundational aspect of currency. Whether this medium is material or immaterial makes little difference. Monetary value is ascribed to works of art mostly as separate from their material value, instead the cultural or hedonic value they generate for the viewer. Ascribing a concrete monetary value to the work of art, therefore, seems paradoxical, because the creative value of art is inherently subjective. When an artwork is entirely conceptual, as in the IKB series, and does not rely on any form of physical existence, an attachment of monetary value seems even more absurd.

The conception of NFTs argues that currency, itself, is also subjective. “Markets are not rational,” explains Sotheby’s photography expert Juliet Hacking, “this is true whether we are speaking of gold, derivatives or carpets. You should not look for an empirical scale of values in a system that serves to identify one image (painting, print or photograph) as worth £1 million and another, equally pleasing to the eye, as worth £200.”16

The crypto-world relies on block-chain technology that turns transactions into publicly-viewable bits of code stored on a chain of servers. The objective of this is to operate a form of value trading that exists outside of state-sanctioned banking. Crypto is a logical result of a digital age where wealth is increasingly attached to ten character account numbers rather than physical assets, like cash. Cash itself is merely a paper certificate that indexes value.

Although Chan is a founding member of Fingerprint DAO, one of the first NFT (and therefore crypto) artwork collectives, he acknowledges that, “skeptics rightly point out that bitcoin is backed by nothing at all. Its value is secured only in the eye of the beholder, and even this perception is hindered by the complete immateriality of the asset. Bitcoin has no physical form to keep in your pocket. Bitcoin has no intrinsic value.”17 If we understand bitcoin here to signify crypto technologies, we must ask ourselves then that crucial question: Why do people pay millions of dollars for these intangible assets?

Vox reporter Terry Nguyen examines this in a conversation with behavioural economist Matt Stephenson at Columbia University. Nguyen writes that “NFTs seem almost counterintuitive to the digital media age; the technology codifies and enforces a metric of scarcity on a digital file that is at odds with the idea of an open internet...For most digital things, like money, this intrinsic, hedonic value wouldn’t make sense. With NFTs, things that were once treated as interchangeable on the digital space...are allowed to exist with this added value that is appealing to a buyer or owner.”18 What is important to note here is the condition of scarcity that this technology creates for digital art interrupts the sense of fluidity largely associated with a digital environment. In the digital age, information and culture is exchanged pretty much freely. Major content sites like Wikipedia and Youtube demonstrate this open exchange concept. Because digital art exists as a visual representation of code, it has no material quality, so it resists the arresting nature of traditional art furnished by the physical aspects of its medium, like paint, fabric, clay, or marble.

O’Dwyer states that “the art [of an NFT] purchased has no physical manifestation. In these cases, controversially, the buyer is essentially purchasing a 256-character string that signifies ownership...Buyers not only have no rights over the future uses of the image, they don’t even have any rights to possess a lasting reproduction.”19 NFT is not a copyright, nor is it a quantifiable thing. “Thing theory” is a philosophical concept that emerged in the 1990s, and was initially postulated by Bill Brown. One element of the concept proposes that material objects hold value based on our perceptions of their usefulness or beneficial qualities, rather than their inherent physicality. Brown distinguishes between objects and things, explaining that objects are the material qualities that retain this use value, whereas things become reduced to their mere material status once they are broken or have lost that use value. He states that “as they circulate through our lives, we look through objects (to see what they disclose about history, society, nature, or culture—above all, what they disclose about us) but we only catch a glimpse of things. We look through objects because there are codes by which our interpretive attention makes them meaningful, because there is a discourse of objectivity that allows us to use them as facts.” What is of use here to this discussion of NFT logic, is Brown’s proposal that our relationship to value is inherently based on perception rather than materiality. In relating this to the NFT concept, we can create a dialectic for attaching value to the ultimately immaterial object.

We could attach these understandings of hedonic value, cultural value, et cetera under one conceptual framework. Essentially, NFT buyers are purchasing something called “cult value” that has, until now, been ontologically separated from visual culture since the creation of print. O’Dwyer formalizes this signified ownership as a sort of “DNA” that allows for reproduction, operating as a source code that has its own, original, discrete qualities.20 Perhaps more accurately, we can think of the NFT as the lab-engineered zygote for the sociologically democratic and regenerative life of digital art.

Walter Benjamin’s Aura and the NFT

In order to understand “cult value”, we must examine an important essay by Walter Benjamin entitled “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility,” written in 1936, which first labelled this concept. Benjamin was a cultural philosopher who identified the changing nature of art when it is able to be reproduced by technological means. For my purposes, it is important to note that Benjamin labels photography as the instigator of this issue, but I shall return to that later.

According to Benjamin, an original artwork is imbued with a sense of authenticity or originality that is connected to the uniquely tangible nature of that artwork. He defines this authenticity as the “aura,” and stipulates that, with the reproduction of art via printmaking and other methods in the modern period, artwork has lost that sense of aura. This is because aura cannot exist without a substantial (in the sense of substance) connection to the original. Benjamin defines the aura as “A strange tissue of space and time: the unique appearance of a distance, however near it maybe.”21 In other words, it is an immaterial sensation that cannot exist without its material foothold. Note too, how aura is defined in terms of distance and time—cultivators of value in cultural perspective.

Referring to Hollywood films and print culture, Benjamin explains that, “Every day, the urge grows stronger to get hold of an object at close range in an image [Bild], or, better, in a facsimile [Abbild], in reproduction.”22 In the present day, this rings true more than ever. The digital world provides a means of destabilizing and encoding images that are available at the touch of a button, or increasingly, at the swipe of a finger. In two seconds, you can view the Mona Lisa on an iphone. But you can’t stand in front of her, holding within your own experience a sense of having witnessed the real thing.

Digital culture, therefore, is a complete removal from the aura, making art and content available to the masses. Natively digital art relies on this disconnect; it is embedded within an intangible universe. NFTs disrupt this understanding of digital by re-attaching the aura through an enforcement of scarcity.

NFTs often feel like this radical concept that is completely disconnected from logic, but they arguably only formalize the artistic ontological crisis that has been ongoing since the industrial era. As I stated earlier, Benjamin points to photography as the instigator for the “Technological reproducibility” of art. I believe that by tracing this artistic dialogue back to the invention of photography in the Victorian era, we can formalize a theoretical relationship for art’s paradoxical nature as commodity and object of devotion.

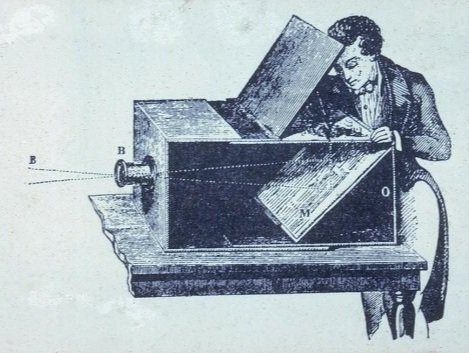

Figure 6.

Portable Camera Obscura, Courtesy George Eastman House, JSTOR.

Figure 7.

Front Cover, William Henry Fox Talbot’s “The Pencil of Nature”, 1844.

The Calotype Process

One of the first successful attempts at securing light on paper was performed by William Henry Fox Talbot, an English polymath, who became frustrated with the artist’s inability to perfectly portray nature, even when using tools like the Camera Obscura: a box with a pinhole that allows for light to be reflected from an object onto the back of the box, and then to be traced over (fig. 6). In his frustration, Talbot said to himself, “How charming it would be if it were possible to cause these images to imprint themselves durably, and remain fixed upon the paper!”22

What I find interesting here is that Talbot does not refer to his own artistic will when creating the images, but envisions the photograph as an automatic process: “to imprint themselves.” The photograph was imagined as the traces of a personification of light—it reached out and touched the paper, as if it had an independent will.

Although Talbot was not the first to dabble in the securing of light on paper, his method became a central tenet to our fundamental understanding of photographic development. His method, was known as the calotype, which comes from the greek words kalos, meaning “beautiful,” and typis meaning “impression.” These beautiful impressions were the result of a laborious, time-intensive process.

In order to create a calotype, a piece of paper must first be washed with a salt solution, and then brushed over with a solution of silver nitrate. The paper is then exposed to an image through the camera obscura. The light refracted from that image will embed itself in the paper, which will then be “fixed”, as Talbot states, by a subsequent wash with alkaline iodide.23 In a way, the chemical wash acts as a net, trapping the fingers of light brushing across its surface. The areas of the white paper that were touched by light became dark, and so the result was a reversed image of the exposure. The darkness became a fingerprint for light. In his own description of his photographic invention, Talbot writes that “The picture, divested of the ideas which accompany it, and considered only in its ultimate nature, is but a succession or variety of stronger lights thrown upon one part of the paper, and of deeper shadows on another. Now Light, where it exists, can exert an action, and, in certain circumstances, does exert one sufficient to cause changes in material bodies.”24

You can see in Figures 8 and 9 an example of a remarkably well-preserved negative and positive image, done in Talbots’ Calotype method. Both are images taken of Hawkhurst Church, in Kent, by photographer Benjamin Brecknell Turner.

Figure 8. (left) Benjamin Brecknell Turner, Hawkhurst Church, Kent: A Photographic Truth, 1852-4, alotype negative.

Figure 9. (right) Benjamin Brecknell Turner, Hawkhurst Church, Kent: A Photographic Truth, 1852-4, Albumen print.

The lighter image is an albumen print made from its negative adjacent. The V&A states that Turner would not have intended for the audience to view the negative. The print was exhibited in Turner’s 1852 catalogue entitled “Photographic Views from nature,” accompanied by a variety of other prints that show the pastoral whimsy for a pre-industrialized English countryside.

An added title for the image is “A Photographic Truth.” Through this title, I believe Turner endeavoured to acknowledge the aim of photography to artificially imitate natural forms. These two images contain microcosms of the negative/positive logic within themselves. Notice how the image is of a church over a body of water. The steeple, the grass, the windows—all of it—is perfectly reflected in the glass-like water in the bottom half of the image. The water acts as a mirror, capturing the essence of the image and reprojecting it. What you are seeing is not the church itself, but a representation of it. The compounding of this philosophical enquiry in the title stipulates that Turner and his contemporaries were vividly aware of the implications photography could have on the precedence of truth-making and knowing. Truth must be related to the original.

Thomas Sutton, an early photographer and producer of waxed calotype negatives, stipulates that the positive print is the end goal of the process in his manual for amateur photographers. He vaults the merits of the calotype process in that it becomes more readily accessible for print-making, as opposed to the daguerreotype, whose end product is a positive print that is not serviceable to printing copies. He breaks down the process of acquiring a calotype negative as such: “The negative, therefore, must first be taken, and that by means of apparatus conveyed to the spot. In it the lights and shadows are all reversed... the position, also of the objects, as regards right and left, is reversed; and to judge of the merits of a negative it becomes necessary to view it by transparency, and with its back to the eye.”25 Here again we see that essential quality of the negative. Negatives are viewed as portals, reflecting pools. By their nature, they act as a transparent film, imprinted with the touch of the image. They are windows to the soul of the past.

Fading

When you go on to the website of the Victoria and Albert museum, and type in “calotype” in their archive record search box, you are presented with a vast number of white pieces of paper, some only containing the faintest delible traces of a building’s horizon.26

Figure 10. (left) William Henry Fox Talbot, Side of Lacock Abbey with Sharington's Tower', 1839, Calotype Paper Negative, Victoria and Albert Museum.

Figure 11. (right) William Henry Fox Talbot, Lacock Abbey entrance arch, 1839, Calotype Paper Negative, Victoria and Albert Museum.

These pieces of paper at one time contained some of the earliest photographs ever taken, but are now reduced to trimmed blank spaces that frame what once was. Although some calotype images survived the last two centuries, it is these nearly-faded photographs that signify something much more interesting about human value creation and perception.

The calotype is the first type of photography to produce a negative, which differentiates it from more popular methods like the daguerreotype. “A major problem in the first two decades of negative/positive photography was that of fading, and it has become the fate of the calotype to be considered today the medium most plagued by it. Countless calotype images have, in fact, been lost to us.”27 Most of the calotypes held by the Victoria and Albert museum are the negatives. The number of positive prints in existence of each negative is rarely known.

Photographic art historian Geoffrey Batchen distinguishes the relationship between negatives and prints rather succinctly when he writes that “The negative is an indexical trace of light, with any tonal variations a chemical, and thus directly physical, response to that light. Photographic prints are one step removed from this tracing; they are an indexical impression of the negative rather than of the subject they portray. These prints are made when light is allowed to travel through the negative and fall onto a piece of light-sensitive paper, thereby re-reversing the tones created in the initial exposure.”28 In photography, there is only one negative. I believe that Batchen’s implication of indexicality is vital to its connection to the NFT. Like the NFT, the negative has the irreplaceable touch of the “real”.

Figure 12. Frame from Promotional Video for Sotheby’s Natively Digital 1.2 NFT Auction.

In the Sotheby’s “Natively Digital 1.2” auction’s promotional video, a distorted white phrase rests against a grey background. “The best curator is time,” it reads. Art auctions rely on provenance as an indicator for value. Like a good vintage wine; the older—the better. The fame of previous owners of a piece adds value to it, because of the cultural perspective of those owners and their roles in society. A work of art’s illustrious history of ownership becomes central to its value. Museums also rely on the work of art’s history to make it worthwhile to keep it in their collections.

What is art? Painting, Photography, Digital

Categorizing photography has always proven a difficult thing. I prefer to look at it as a tool that can go far beyond the scope of what was initially imagined for it. Talbot insists in his essay “The Pencil of Nature,” that the art is only at its beginning at the time of his writing.

Although Talbot first envisioned photography as a measure of nature’s ‘pencil’, a sure belief in its artistic capacities, photography was, at first, not really viewed as an art form by the consumer public. Art, to the early Victorians, had to be more directly connected to the artists’ hand. It could not be mechanical. The Pre-Raphaelites best encompassed this in their efforts to achieve “maximum realism,” through poetic forms.29 It was not merely the end-product that fascinated them, but the artist’s painstaking labour and profound genius that was poured into the artistic object. Paintings were valued in terms of their ability to represent the lifelikeness of the natural world. The most adept painters in the Baroque and Renaissance could fashion soft human flesh out of marble, trace the lineaments of the face in flecks of paint, draw out the intransience of light in glass, or mold a sense of depth in the artificial space. To recreate reality in perfect form was the goal of art. But, in the nineteenth century, photography created a disturbance in the artistic psyche. With the camera, artistic realism became anachronistic.

Initially, however, photography was only viewed as a painter’s tool, one that could hold the finer details of an image they would later paint, somewhere outside of the mind. It alleviated the need for quick sketches in pencil and watercolour that might misconstrue the true nature of a scene. In order to be considered art, it was believed that art had to hold some sort of conceptual practice, some type of higher spirit. This would then create its aura. The dictionary definition of art stipulates that art is “the expression or application of human creative skill and imagination, typically in a visual form such as painting or sculpture, producing works to be appreciated primarily for their beauty or emotional power.”30 It is, therefore, creativity and imagination—spirit—applied or expressed.

Our goal is not to define art, but to figure out what aspect of it creates cult value, and thus financial value. Is it the spirit? Or the application? Thus we have another paradox, in the triangulation between material, content, and aura. Is the aura, which defines value, more intrinsically connected to its materiality or its content? If art must have a material element to be considered art, then how can purely conceptual art, like Immaterial Zones, lack any material quality?

Today this is the same thing that troubles the average consumer in relation to NFTs, especially in examples like Chan’s. With only form, and without imagery, it is difficult to consider NFTs as art. After all, why would anyone pay for a blank computer screen? I would argue that it is aura that determines value, and aura is inherently both tied to the substantive nature of an object and the social/historical/ideological concept which that object symbolizes.

It wasn’t truly until a few decades after Talbot completed his experiments that photography would come to be viewed as an art form. Initially, it fell under the realm of chemists, botanists, and law enforcement, as a tool for pure documentation.31 Photography was believed to be objective in its self-moving nature. Remember that, to them, the photograph created itself, and did not rely on an artist’s hand. Later photographic societies, like the Linked Ring and the Photo-Secessionists, were among the first to promote the idea that the photographer’s hand did influence the camera, and thus the final picture. The photographer was not a passive bystander to the object, but articulated its every detail, from the framing of the image to the positioning of subjects to the edited blurs, shades, and colours added directly to the film in post-production. Proto-art photographers like Julia Margaret Cameron tried to imbue portraits with a poetic sensibility, like contemporary Pre-Raphaelite paintings. She would allow brief movements in her photographs, which would efface the strict detailing of the paintings and wash the photographic subjects with an ethereal glow.32 She also chose not merely to document faces, but to place them within literary contexts, setting up theatrical scenes and turning her maid-servants into the characters of nymphs and angels. Cameron’s work was among the first to be exhibited as art.33

By the 1860s, nearly anyone, no matter their rank or status, could have access to a perfect likeness of themselves or a family member in the form of a photographic portrait, with the increasing popularity of the ‘Carte de Visite’.35 Until that point, only the wealthy could afford to have their portraits painted. The mechanical, relatively inexpensive process allowed for images to n4t only become more automatic, but more attainable.

Benjamin discusses the Victorian photographic paradigm shift in his aforementioned essay. He writes that, “The nineteenth-century dispute over the relative artistic merits of painting and photography seems misguided and confused today. But this does not diminish its importance, and may even underscore it. The dispute was in fact an expression of a world-historical upheaval whose true nature was concealed from both parties. Insofar as the age of technological reproducibility separated art from its basis in cult, all semblance of art’s autonomy disappeared forever. But the resulting change in the function of art lay beyond the horizon of the nineteenth century.”35 In this, Benjamin refers to the rise of avant-gardism, in movements like expressionism, dada, cubism, and the continued abstraction of art. This abstraction would eventually culminate in entirely conceptual works like Klein’s Immaterial Zones of Pictorial Sensibility, or his trademark blue.

For the Collector

In practice, collecting photography is something altogether different from collecting NFTs. Juliet Hacking takes pains to explain the difference between the positive and the negative; while the negative has a closer tie to the object it represents, it is not intended as the end product. “What appears illogical is perhaps straightforward: collecting negatives would be like collecting the sculptor’s mould rather than the sculpture.”36 Turner, indeed, did not intend for any of his negatives to be displayed as they are by the Victoria and Albert museum.37 Especially when considering the fact that many old negatives, like Talbot’s calotypes, are subject to fading with time, it becomes increasingly obvious that these old photographs don’t meet the mark for saleable material. But, we must not forget that these archival photographs, despite being void of content, still have perceivable value. Otherwise, why would the museum hold onto them?

Andre Bazin quite perfectly articulated the reason we cherish photographs regardless of their pictorial content in 1958, when he stated that, “Only a photographic lens can give us the kind of image of the object that is capable of satisfying the deep need man has to substitute for it something more than a mere approximation, a kind of decal or transfer. The photographic image is the object itself, the object freed from the conditions of time and space that govern it. No matter how fuzzy, distorted, or discolored, no matter how lacking, in documentary value the image may be, it shares, by virtue of the very process of its becoming, the being of the model of which it is the reproduction; it is the model.”38

Negative/positive photographic methods were originally patented by Talbot and were not allowed to be used for commercial purposes. Therefore, until the founding members of the London Photographic Society took him to court in the 1850s, Daguerrotypy was most commonly used by commercial photographers, especially for portraiture. Once Talbot’s patent was released and new methods based on his negative/positive concept were introduced with more permanency, via the carbon printing process, for example, calotype-based photography took over the market, and daguerreotypes became antiquated. Even today, when analogue photographs are sold, they are sold in editions printed from the negative. Often, a series of prints is created, numbering only ten or twenty. It is not only the age of the prints, but the number of them, that informs their financial value. The fewer becomes the rarer, which becomes the more-prized. By doing this, analogue photographers and their estate holders can continually re-create scarcity by making more prints.39 Although the digital art object might exist on thousands of computers, there is only one codified right to ownership - the NFT. The photographic negative, therefore, is the value-container that all the other objects that emanate from it—in this case, positive prints—rely on to imbue them with value.

Conclusion

The content of this foray into value and art could have applications in many realms outside of the purely theoretical. Chan’s sale of “Pictorial Sensibility” is only one example of its kind. Millions upon millions of dollars are funneled through cryptocurrency’s massive servers. If we are to become increasingly reliant on NFTs for ascertaining art market value, as predicted by Deloitte’s report, we will have to create ways that maintain the aspect of public accessibility while mitigating climate change.

Although I have thus far drawn an analogy between the role of negatives in photography and NFTs in digital art, I must confess that there is one key difference between the two; whether or not the ‘aura’ of either is organic or artificial.

In truth, photographic negatives are not entirely the same thing as the NFTs, in that they are not traded in exactly the same terms. The negative is the blueprint for a print, whereas the NFT is the saleable product. Both, however, are alike in their connection with originality. I would perhaps even go as far as arguing that the perceived ‘illogic’ of collecting negatives also surrounds the same confusion surrounding NFT collection. The thing is, NFT-aura is encoded, rather than native. Digital art is essentially, irrevocably reproducible, so the NFT concept is not a new thing, but rather an old reaction to the new.

The enforcement of scarcity is capital’s effort to re-imagine itself in the digital age. Scarce digitality, however, is an oxymoron. We are seeing this increasingly in the art world; attempts to make the once attainable, unattainable.

Endnotes

“Ancient Vestry, Calvert Jones in the Cloisters at Lacock Abbey: Fox Talbot, William Henry: V&A Explore the Collections,” Collections: Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed December 7th 2021, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1387871/the-ancient-vestry-calvert-jones-photograph-fox-talbot-william.

M.H. Miller, “Art World Returns to a New Normal,” New York Times, June 14, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/14/t-magazine/art-issue-new-normal.html?smid=url-share.

Steve Kaczynski and Scott Duke Kominers, “How Nfts Create Value,” Harvard Business Review, November 19, 2021, https://hbr.org/2021/11/how-nfts-create-value.

Kaczynski, “How Nfts Create Value,” 2021.

Kaczynski, “How Nfts Create Value,” 2021.

“Introduction,” in Deloitte Art & Finance Report 2019 - 6th edition, (Luxembourg: Deloitte, 2019), accessed December 7th, 2021, https://www2.deloitte.com/lu/en/pages/art-finance/articles/art-finance-report.html.

Rachel O’Dwyer, “A Celestial Cyberdimension: Art Tokens and the Artwork as Derivative,” (Circa, December 2018), 10.

Rebecca Solnit, “Yves Klein and the Blue of Distance,” New England Review (1990-) 26, no. 2, (2005), 178, accessed December 7th, 2021, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40240721.

Solnit, “Yves Klein and the Blue of Distance,” 179.

Mitchell F Chan, “Digital Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility: Blue Paper,” (Self-Published, Inter-Planetary File System, August 2017), 6, https://ipfs.io/ipfs/ QmcdKPjcJgYX2k7weqZLoKjHqB9tWxEV5oKBcPV6L8b5dD.

Chan, “Digital Zones…”, 21.

Carol Duncan, Civilizing Rituals : Inside Public Art Museums, London: Routledge, 1995.

"money, n.", Oxford English Dictionary Online, December 2021, Oxford University Press, https://www-oed-com.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/view/Entry/121171?rskey=ZSwBOF&result=1&isAdvanced=false.

Juliet Hacking, “Buyer Aware,” in Photography and the Art Market, (London: Lund Humphries in association with Sotheby’s Institute of Art, 2018), 44.

Chan, “Digital Zones…”, 11.

Terry Nguyen, “Value of Nfts, Explained by an Expert,” Vox, March 31, 2021, https://www.vox.com/the-goods/22358262/value-of-nfts-behavioral-expert.

O’Dwyer, “A Celestial Cyberdimension…”, 5.

O’Dwyer,“A Celestial Cyberdimension…”, 5.

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility [First Version],” Trans.Michael W. Jennings, Grey Room, no. 39 (2010), 15. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27809424.

Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility [First Version],” 16.

William Henry Fox Talbot, The Pencil of Nature (London: Longman, Brown, Green, & Longman, 1844), 12.

Talbot, The Pencil of Nature, 21.

Talbot, The Pencil of Nature, 12.

Thomas Sutton, “Introduction,” in The Calotype Process : A Hand Book to Photography on Paper, (London: J. Cundall and by S. Low, 1855), 2.

Richard Brettell, et al, Paper and Light: Calotype in France and Great Britain, 1839-70, (Boston: David R. Godine, 1984), 12.

Geoffrey Batchen, Negative/Positive: A History of Photography, (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2021), 3.

Tate, “Pre-Raphaelite – Art Term,” Tate, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/pre-raphaelite.

“art, n.1”, Oxford English Dictionary Online, December 2021, Oxford University Press, https://www-oed-com.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/view/Entry/11125?rskey=eGMMyN&result=1&isAdvanced=false.

Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (1986): 3–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/778312.

Robin Kelsey, “Julia Margaret Cameron Transfigures the Glitch,” in Photography and the Art of Chance, (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 20150, https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674426177.

Julian Cox, Julia Margaret Cameron : The Complete Photographs, (Los Angeles, CA: Getty Publications, 2003).

Ronald S. Coddington, “Cardomania!: How the carte de Visite Became the Facebook of the 1860s,” Military Images 34, no. 3 (2016), 12–17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24865727.

Benjamin, “The Work of Art…”, 20.

Hacking, “Buyer’s Aware,” 34.

“A Photographic Truth: Benjamin Brecknell Turner: V&A Explore the Collections.” Victoria and Albert Museum, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1430925/a-photographic-truth-photograph-benjamin-brecknell-turner.

André Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” Trans. Hugh Gray, in Film Quarterly 13, no. 4 (1960), 8, https://doi.org/10.2307/1210183.

Hacking, “Frequently Asked Questions about the Art-Photography Market” in Photography and the Art Market, 25-28.

Bibliography

“Ancient Vestry, Calvert Jones in the Cloisters at Lacock Abbey: Fox Talbot, William Henry: V&A Explore the Collections.” Collections: Victoria and Albert Museum. Accessed December 7th 2021. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1387871/the-ancient-vestry-calvert-jones-photograph-fox-talbot-william.

“A Photographic Truth: Benjamin Brecknell Turner: V&A Explore the Collections.” Victoria and Albert Museum. Accessed December 7th 2021. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1430925/a-photographic-truth-photograph-benjamin-brecknell-turner.

"art, n.1". Oxford English Dictionary Online. December 2021. Oxford University Press. https://www-oed-com.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/view/Entry/11125?rskey=eGMMyN&result=1&isAdvanced=false.

Batchen, Geoffrey. “Introduction.” in Negative/Positive : A History of Photography. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2021.

Bazin, André. “The Ontology of the Photographic Image.” Translated by Hugh Gray. Film Quarterly 13, no. 4 (1960): 4–9. https://doi.org/10.2307/1210183.

Benjamin, Walter, and Michael W. Jennings. “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility [First Version].” Translated by Michael W. Jennings. Grey Room, no. 39 (2010): 11–38. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27809424.

Brettell, Richard, and Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and Art Institute of Chicago. Paper and Light: Calotype in France and Great Britain, 1839-70. Boston, MA: David R. Godine, 1984.

Chan, Mitchell F. “Digital Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility: Blue Paper.” Self-Published, Inter-Planetary File System, August 2017. https://ipfs.io/ipfs/QmcdKPjcJgYX2k7 weqZLoKjHqB9tWxEV5oKBcPV6L8b5dD.

Coddington, Ronald S. “Cardomania!: How the Carte de Visite Became the Facebook of the 1860s.” Military Images 34, no. 3 (2016): 12–17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24865727.

Cox, Julian, Julia Margaret Cameron, and Colin Ford. Julia Margaret Cameron : The Complete Photographs. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Publications, 2003.

Duncan, Carol. Civilizing Rituals : Inside Public Art Museums. London: Routledge, 1995.

“Digital Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility.” Sotheby's Metaverse. Accessed December 7th 2021. https://metaverse.sothebys.com/natively-digital/lots/digital_zone_of_immaterial_ pictorial_ sensibility.

Hacking, Juliet. Photography and the Art Market. London: Lund Humphries in association with Sotheby’s Institute of Art, 2018.

“Introduction,” Deloitte Art & Finance Report 2019 6th edition Luxembourg: Deloitte, 2019. Accessed December 7th, 2021. https://www2.deloitte.com/lu/en/pages/art-finance/ articles/art-finance-report.html.

Kaczynski, Steve, and Scott Duke Kominers.“How Nfts Create Value.” Harvard Business Review, November 19, 2021. https://hbr.org/2021/11/how-nfts-create-value.

Kelsey, Robin. Photography and the Art of Chance. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674426177.

Lambert, Nick. “Beyond Nfts: A Possible Future for Digital Art.” Itnow 63, no. 3 (2021): 8–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/itnow/bwab066.

Longman, Brown, Green, & Longman, 1844. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/BLMZME536800518/NCCO?u=crepuq_mcgill&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=9392a85a&pg=1.

Miller, M. H. “Art World Returns to a New Normal.” New York Times, June 14, 2021. https:// www.nytimes.com/2021/06/14/t-magazine/art-issue-new-normal.html?smid=url-share.

"money, n.". Oxford English Dictionary Online. December 2021. Oxford University Press. https://www-oed-com.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/view/Entry/121171?rskey=ZSwBOF&result=1&isAdvanced=false.

Nguyen, Terry. “Value of Nfts, Explained by an Expert.” Vox, March 31, 2021. https://www.vox.com/the-goods/22358262/value-of-nfts-behavioral-expert.

O’Dwyer, Rachel. “A Celestial Cyberdimension: Art Tokens and the Artwork as Derivative.” Circa, December 2018. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27029628.

Sekula, Allan. “The Body and the Archive.” October 39 (1986): 3–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/778312.

Solnit, Rebecca. “Yves Klein and the Blue of Distance.” New England Review (1990-) 26, no. 2 (2005): 176–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40240721.

Sutton, Thomas. The Calotype Process : A Hand Book to Photography on Paper. London: J. Cundall and S. Low, 1855. Nineteenth Century Collections Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/BAEDZO767072329/NCCO?u=crepuq_mcgill&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=8fce638b&pg=1. Accessed 13 Dec. 2021.

Talbot, William Henry Fox. The Pencil of Nature. London: Longman, Brown, Greens, and Longmans. 1844-46, Nineteenth Century Collections Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/BLMZME536800518/NCCO?u=crepuq_mcgill&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=9392a85a&pg=1.

Tate. “Pre-Raphaelite – Art Term.” Tate. Accessed December 7th 2021. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/pre-raphaelite.

“Transfer of A Zone of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility...” Yves Klein. Accessed December 7th 2021. http://www.yvesklein.com/en/oeuvres/view/640/transfer-of-a-zone-of-yyimmaterial-pictorial-sensibility-to-m-blankfort-pont-au-double-paris.

Turner, Benjamin Brecknell. Photographic Views from Nature. Publisher Unknown, 1852. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/BLNEDC611337463/NCCO?u=crepuq_mcgill&sid=bookmark-NCCO&xid=3fc16f15&pg=58.