A Queer Analysis of Botticelli’s Venus and Her Role as Pop-Cultural Icon

Written by Sam Lirette

Edited by Paige Suhl

Preface

My name is Sam Lirette. I am a twenty-two-year-old, white, queer, Québécois art historian. I state this firmly, as I argue for the radical personalization of the field of art history—for the active acknowledgement of the self. I believe recognizing the limits of objectivity is paramount, and so is understanding one’s biases. As a result, considering the highly personal motivations behind this research paper, it is necessary to underline my own subjective position as a scholar. Specifically, I wish to note how my lived experiences as a queer individual have shaped my research in tremendous ways. During the formative years of my youth, I quickly noticed the ways in which my gender expression and sexuality deviated from the norm. Naturally, as a mode of survival, I gravitated towards images which made me feel empowered and not only legitimized but celebrated my queer existence. My research represents an intense desire to understand this on an academic level. Hence, I embark on this personal quest—one which I firmly believe can benefit both the field of art history on a broader scale, as well as queer readers who have been marginalized by narrow-minded narratives.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Professor Angela Vanhaelen and my classmates for their continuous encouragement during the development of this research paper. I would also like to thank my family and closest friends for their unwavering support throughout the years. It all means the world to me.

Introduction

The art historical canon, as a constructed body, is defined by the context in which it was created. Most notably, the canon has long been framed by heteronormative and thus often exclusionary narratives. This has consequently resulted in the erasure of any possible queer interpretations of well-known artworks. In this research paper, I aim to deconstruct the canon and broaden the ways in which canonical artworks may signify by performing a queer analysis of the figure of Venus in Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus of c. 1485 (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, c. 1485, Tempera on Canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

An important rediscovery and fascination with Botticelli’s art occurred in the late nineteenth century. Although considerable research has been conducted on Botticelli’s life and allegorical works of art, most of this research has followed a traditional art historical narrative and fails to answer some crucial questions: How may the artwork signify to queer viewers? And why are queer artists—or artists with significantly queer audiences—appropriating his canonical works? By building upon this preliminary research on both the history and allegorical meanings of Botticelli’s oeuvres, I shall acknowledge the held consensus on his masterpieces, while simultaneously providing new and non-normative interpretations.

Methodologically, my research is concerned with conducting a temporal examination of the figure of Venus. This, however, is performed through a queer lens. My first priority is thus to provide an understanding of the word ‘queer,’ while deconstructing traditional notions of gender. My analysis of the artwork itself begins far before the advent of the Renaissance, as exploring the origins of the cult of Venus/Aphrodite in Ancient Rome and Greece proves crucial in developing a contextual understanding of the icon’s everlasting cultural presence. Subsequently, I examine Florentine life and sexuality, namely the evident homoeroticism present at the court of the Medici, which provides insight on the artistic use of Venus—goddess of love and sex. Furthermore, I observe the ambiguous visual qualities and complexities found in Botticelli’s masterpiece, which I argue, appeal to the queer eye in the sense that they allow for a wide range of non-normative interpretations. This involves an in-depth analysis of the affect of shame, specifically concerning the pose of the Venus Pudica. These key objectives are achieved through the application of queer theories and culminates in understanding the impact of Botticelli’s Venus on contemporary queer artists and popular culture. In this regard, I conclude my research by conducting a case study of Lady Gaga’s infamous ARTPOP (2013), in which the pop icon makes significant lyrical and visual use of the icon of Venus.

In brief, I argue that Botticelli’s Venus exhibits a dual, seemingly paradoxical nature: she is both shamed into modesty yet empowered by her sexual agency. Consequently, she may be understood as a symbol of sexual— and thus societal emancipation for oppressed and marginalized individuals.

Queer: A Definiton

The word ‘queer’ originally meant ‘strange’ or ‘peculiar,’ and by the late nineteenth century—precisely when paintings like The Birth of Venus entered the art historical canon—it began to be used as a pejorative term against those who expressed same-sex desires.1 However, in the late twentieth century, the word was reclaimed by queer activists. Today, it acts as an umbrella term for anyone who is not strictly heterosexual or cisgender, and the term continues to be associated with “authors, artists, themes or representations” pertaining to the LGBTQ community.2

‘Queer,’ in its very essence, resists a clear definition and instead signifies anything or anyone deviating from the norm. As defined in the ground-breaking work of queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, the word may be employed in multiple ways. Most notably, it is defined as the encompassing range of possible meanings which exist when gender or sexuality is impossible to define.3 Therefore, performing a queer analysis involves going beyond heteronormative assumptions—about the context, the artist, and the viewers of a particular artwork. In other words, employing queer theory involves taking a deliberate position against normative or dominant modes of thought.4

In this research paper, I perform a queer reading of The Birth of Venus. I’m not concerned with deciphering the sexual identity of Botticelli, but instead want to develop a non-normative understanding of his Venus and her legacy as an icon for queer artists and audiences. This revolves around two crucial questions: How can the figure Venus be read through something other than the heterosexual, male gaze? And what can the goddess symbolize for viewers who identify as queer?

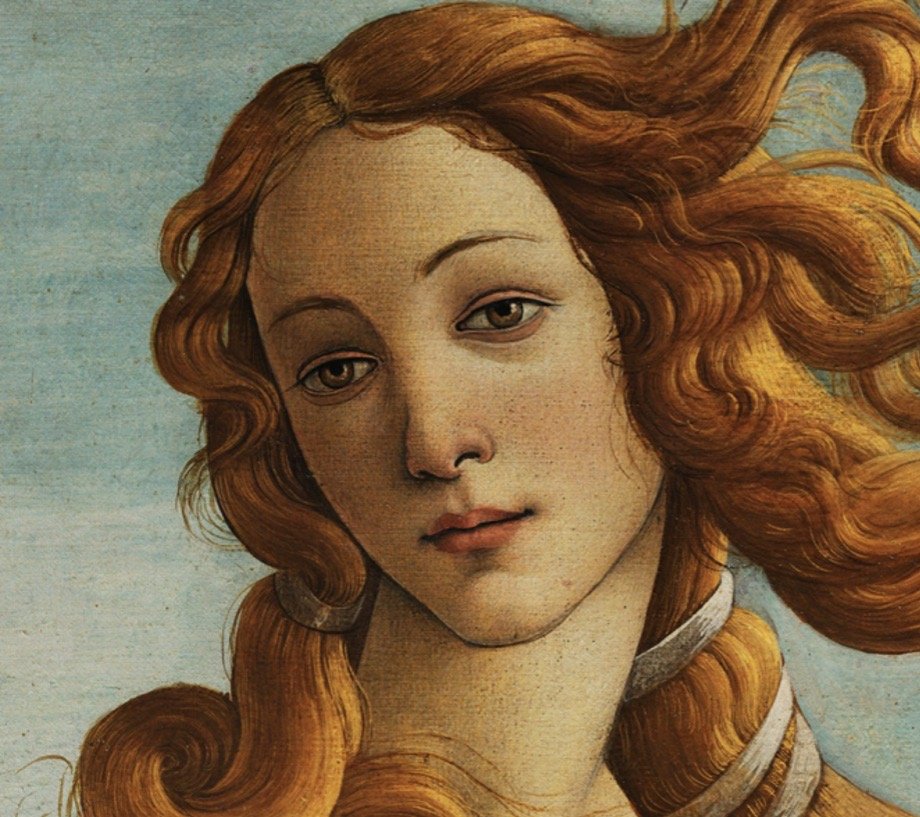

Gender as a Performance: Venus as the Quintessence of Femininity / As the Queen of Camp

Gender theorist Judith Butler stresses how gender is not a static identity deriving from an innate place; rather, it is an identity positioned within time which is constructed from a series of repeated acts.5 Masculinity and femininity are learned behaviours. Gender may thus be understood as a performative act, which audiences and actors themselves come to believe and uphold as reality.6 In terms of the gender binary, Butler considers whether the notion of ‘woman’ is socially constructed in a way to specifically position it as the oppressed gender.7 This becomes an important consideration, as I argue Venus (fig. 2) may be understood as the epitome of classical femininity and beauty. This is made evident by her physique, long blond hair, and alabaster skin. Is her construction into the ideal female a sign of oppression? And is her position indicative of shame? These questions shall be explored further on. Although the goddess does not explicitly subvert notions of gender, I argue she may signify differently to queer viewers by displaying notions of shame in an ambiguous manner.

Figure 2. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (detail), c. 1485, tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

The gender binary, I would argue, serves to control members of society and their behaviour. After all, performing one’s gender in an ‘incorrect’ manner may result in societal punishment.8 One who fails to uphold the illusion of gender often causes anxiety within those who do. For instance, Butler notes how the sight of a crossdresser on stage may elicit laughter and pleasure within an audience, yet the site of the same crossdresser in real life may cause severe distress and fear, and result in violence.9 When the transgression of gender norms is obviously stated as an act, it has the potential to be funny. When it is part of the larger ‘stage’ of everyday life, which ostensibly is also an act, it becomes a threat. In The Birth of Venus, I would argue that Venus successfully performs femininity. Consequently, she does not elicit anxiety within viewers. She is clearly female. Venus, as the goddess of love and sex, is the epitome of femininity. However, by being a hyperbolic representation of femininity, I argue she may be read as a camp iteration of the feminine construct. In other words, she may even be read as somewhat of a drag queen. This is precisely where queer viewership comes into play. This representation of the goddess may signify differently to different viewers; she may appear as an ideal, modest, and pleasing female figure to the heterosexual male viewer, but as an overtly camp, over-the-top, extravagant representation of femininity to queer audiences. Camp, as described by Susan Sontag, involves an admiration of the unnatural, of “artifice and exaggeration,” and it is somewhat of a “private code among small cliques.”10 Thus, camping the canonical figure may be read as a form of subversion by queer viewers; it reverts the notion of exclusivity and empowers the queer viewer. Camp involves pointing out the absurdities of societal constructs by playing into them, and here, the notions of gender and its stylizations can be made fun of. Sontag puts it perfectly: “Camp sees everything in quotation marks. It is…not a woman, but a ‘woman.’ To perceive Camp in objects and persons is to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role. It is the farthest extension, in sensibility, of the metaphor of life as theater.”11 Moreover, camp is distinctly queer and involves the active acknowledgement of gender constructs. Viewing the figure of Venus as camp thus calls attention to such marginalizing conceptions and ultimately dismantles them. This notion not only provides a non-normative perception of The Birth of Venus but proves crucial in developing an understanding of the goddess as inspiration for queer artists and viewers.

Gender and Sexuality in Fifteenth-Century Florence: Understanding the One-Sex Model

Now that contemporary gender constructs have been discussed at length, it becomes important to understand how gender and non-normative sexuality were perceived in fifteenth-century Florence (precisely when and where The Birth of Venus was created) as well as when the painting entered the art historical canon in the nineteenth century. Historian and sexologist Thomas Laqueur argues that a radical change in attitudes concerning human sexual anatomy occurred in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe. Most significantly, Laqueur notes:

“The record on which I have relied bears witness to the fundamental incoherence of stable, fixed categories of sexual dimorphism, of male and/or female. The notion, so powerful after the eighteenth century, that there had to be something outside, inside, and throughout the body which defines male as opposed to female and which provides the foundation for an attraction of opposites is entirely absent from classical or Renaissance medicine.”12

Evidently, such dichotomous ideas on sex and gender were created at the time that artworks such as Botticelli’s were rediscovered and became part of the canon. Therefore, attempting to understand artworks like The Birth of Venus solely through this anachronistic model is fallible, as the masterpiece predates such conceptions. Laqueur states that during the Renaissance, there existed no clearly juxtaposed sexes; instead, there was the idea of a single sex, of which there were more perfect (male) and less perfect (female) exemplars.13 It was over three and a half centuries after Botticelli painted The Birth of Venus that such categories of ‘male’ and ‘female’ were clearly defined as opposites, which served not only to segregate individuals into two distinct classifications, but to propel heteronormative models and arguably further position ‘woman’ as the oppressed sex (as Judith Butler denotes). This more fluid understanding of both sex and gender, which existed during the creation of the artwork, aids in understanding the The Birth of Venus through a queer lens. Significantly, Laqueur notes: “So-called biological sex does not provide a solid foundation for the cultural category of gender, but constantly threatens to subvert it.”14 Thus, observing the fluidity of both gender and sexuality present in fifteenth-century Florence becomes important in understanding the context within which The Birth of Venus was created, and furthermore, the ways in which it may signify to queer viewers of today.

Sodomy in Fifteenth-Century Florence

In the same vein as Laqueur, Italian Renaissance specialist Michael Rocke argues: “Simply to project current Western conceptions of homosexuality—which are dominated by the notion of a permanently deviant and distinct minority—onto same-sex erotic relations in past or other societies inevitably tends to misrepresent their historical and cultural specificity.”15 Rocke performs an in-depth analysis of sodomy—specifically sex between men—and its persecution in Florence from the years 1478 to 1502. In brief, he notes how same-sex sodomy in late-fifteenth-century Florence usually involved an adult male who took the ‘active,’ dominant role with a ‘passive’ adolescent.16 This custom, known as pederasty, dates to Ancient Greece and Rome, thus outlining a broad revival of Greco-Roman customs which appeared to go beyond art and philosophy. Furthermore, the custom underscores the conventions behind sexual relations between males, which Rocke argues operated within a precise “framework of cultural premises about masculinity, status, honor, and shame.”17 This notion of shame will prove important when further analyzing Botticelli’s painting. This structure outlines a certain rite-of-passage into manhood, and consequently played an important role in the construction of masculinity.18 Significantly, the custom was bound by strict conventions; the older man had to take the active role, while the younger boy took the passive role. Also, once teens reached a certain age, they were deemed men and it was no longer appropriate for them to take that passive role.19 However, there were indeed outliers: There were boys who aged and continued to play the passive role, and there were elderly men who took on the passive role, too.20 The custom took on the complex position of being somewhat normative, but still persecuted and bound by strict rules. If this custom was so prevalent in fifteenth-century Florence, it seems as if it cannot fit our definition of ‘queer.’ However, again, it is important to note historical specificity. And so, although it is anachronistic to use the term queer, I argue that the differing, considerably more fluid way of understanding sexuality at the time that The Birth of Venus was painted allows us to understand exactly how the artwork can signify a range of possibilities for viewers. For queer viewers of today who feel bound by contemporary constructs, that could mean a certain freedom to express their sexuality.

Furthermore, it is impossible to perfectly outline the sexuality of the men of the fifteenth century who engaged in sodomy, as many did in fact marry women and have children. In this sense, we are reminded of Sedgwick’s definition of queer. When it is impossible to pinpoint sexuality, there exists much more room for interpretation. And after all, the term homosexuality itself was only coined in 1869.21 The freedom from labels here allows us to read paintings like The Birth of Venus against the grain—to read it beyond heteronormative standards.

Homoeroticism at the Court of Medici: Donatello's David

Nearly all Florentine men were incriminated for engaging in sodomy at some point or another during this time; yet, it was rather accepted in Florentine society, especially during Lorenzo ‘the Magnificent’ de’ Medici’s reign from 1469 to 1492.22 Specifically, Lorenzo’s fostering of humanistic and neo-Platonic ideals created a much more tolerant environment for sodomy in Florence for all citizens, not just the elite.23 Notably, Rocke remarks how the active persecution of sodomy “relaxed significantly, if not completely, during the mid-1480s to the early 1490s.”24 Therefore, I argue that the rise in tolerance (and ostensibly active celebration) of sexual fluidity which occurred during Lorenzo’s reign emphasizes a time of relative sexual freedom. Consequently, this allowed for works such as The Birth of Venus to be produced. Fascinatingly, openly homoerotic works were also being created, even decades prior to Lorenzo’s rule. Donatello’s David is a prime example of this (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Donatello, David, c. 1440s, bronze, 158 cm, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

Figure 4. Back view of Donatello’s David, c. 1440s, bronze, 158 cm, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

From the front, Randolph notes how the figure is “readily sexed” with the aid of his visible genitalia which positions him within the category of ‘male.’30 However, when viewing the David from behind (fig. 4), this rigidity unravels. There are no clear identifying features for viewers to categorize the figure with. Instead, Randolph underlines how it is “the feathery caress of the wing that commands attention.”31 Scholars have often avoided addressing this notably erotic feature—a feature which suggests not only a sensual play of feather on skin but may even point to the boy’s penetrability.32 I argue this overlook may suggest a certain level of discomfort within scholars—a certain anxiety which arises when visual evidence clearly transgresses heteronormativity. Moreover, I argue that this desire to gloss over homoerotic features not only fails to note the complex desires and cultural gazes of fifteenth-century Florentine men but results in a certain queer erasure. This is crucial historical information that has been deliberately omitted from the canon for its deviation from heteronormative standards. In fact, Randolph reiterates the words of Rocke, noting how same-sex sexual relations—which were often intertwined with homosocial bonds—were fundamental in the construction of Florentine society and even allowed for the intermingling of individuals from differing social classes.33

Representations of Venus: On the Origins of the Goddess

So far, I have explored notions of sexuality and gender (both in the contemporary and fifteenth-century Florentine contexts) to deconstruct heteronormative conceptions of the art historical canon and provide a basis for understanding how Botticelli’s Venus may signify to queer viewers. Now, I wish to examine the origins of the figure of Venus to further drive my argument.

Although deserving of greater attention, I wish to briefly touch upon the work of Walter Benjamin on the notion of the aura. His essay supports my argument concerning the ways a single figure may signify differently to different groups. Benjamin’s words appear remarkably relevant to my research, as he states:

An ancient statue of Venus, for instance, existed in a traditional context for the Greeks (who made it an object of worship) that was different from the context in which it existed for medieval clerics (who viewed it as a sinister idol). But what was equally evident to both was its uniqueness—that is, its aura. Originally, the embeddedness of an artwork in the context of tradition found expression in a cult. As we know, the earliest artworks originated in the service of rituals…This ritualistic basis, however mediated it may be, is still recognizable as secularized ritual in even the most profane forms of the cult of beauty…which developed during the Renaissance and prevailed for three centuries.34

Coincidently, Benjamin employs the example of Venus to explain the notion of the aura. The same image of the goddess, through time and space, signifies differently to every group which encounters it. This is precisely where I wish to insert queer viewers into the mix. If a representation of Venus was an object of worship for the Ancient Greeks, or an idol for medieval clerics, what can it be for contemporary queer viewers? How may its aura translate through time? If the goddess became part of a cult of beauty for Renaissance viewers, what is she to us today? These are complex questions that cannot be answered succinctly, though I argue simply posing them may shed light on the goddess’ malleable qualities.

We may begin to visualize the transfer of aura by understanding the origins of the goddess Venus. Firstly, she is the Roman equivalent of the Greek Aphrodite. Aphrodite herself derives from a predecessor: the Ancient Mesopotamian warrior goddess Ishtar, known as the Queen of Heaven.35 Although early images of an armed Aphrodite are well documented in Sparta and Argos, the goddess appears to have slowly lost her associations with war over time.36 Aphrodite, and by extension Venus, appears to be rather malleable; the goddess takes on a role relevant to a particular socio-political situation or cult. In the contemporary sense, may she not act as a cult figure for the marginalized—for those who feel oppressed by norms? Could she not become an inspiration for those struggling with their sexuality and/or gender? Moreover, the origin myth of Aphrodite further propels this argument. The goddess was born from a violent act of emasculation; she rose from the foam which formed from her father’s genitals after the god Cronus had “cut them off and thrown them into the sea.” 37 If Aphrodite was born from an act of castration, what could that mean in broader terms? Could that be interpreted as the blossoming of the underdog, which came from the literal castration of the oppressor? Clearly, I argue that the goddess may symbolize the feminine good which comes from the overthrowing of masculine tyrannical power. It is significant that Aphrodite is known as “the first deity to be given clearly anthropomorphic characteristics,” or more importantly, “a detailed female identity.”38 However, she is not portrayed as a maternal figure like Demeter, but instead takes the role of pre-maternal beauty as her aesthetic aspects are always emphasized.39 As Barbara Breitenberger makes evident, the goddess is frequently depicted as “an irresistible seductress” in literature and art.40 This is underlined in the Homeric Hymns, where she is put into contrast with warrior goddesses like Hera and Athena.41 Here, I would argue, her beauty is her weapon. In one particular story, Aphrodite uses her different modes of appearance to manipulate her lover. First, she appears as a prudish girl not to frighten him, then as a femme fatale to make him desire her, and finally as a threatening goddess.42 In the hymn, it is Aphrodite who takes on an active role in her sexual pursuits. As Breitenberger puts it, “she transgresses mortal female nature by claiming active sexual desire, which is normally exclusively the prerogative of men.”43 Clearly, although stripped of her early warrior-like associations, Aphrodite remains completely in control. She exhibits an astounding amount of sexual agency, which is precisely how I argue she may serve as an inspiration for modern queer viewers. On the same notion of subverting gender norms, Breitenberger notes how there were certain rituals in Ancient Greece where women took on the roles of men, such as with the festival of Hybristica in Argos.44 These details prove important in understanding Botticelli’s own inspirations for depictions of Venus, as the artist appears to have known at least parts of the Homeric Hymns.45

Venus and Mars

Before exploring my main object of analysis, The Birth of Venus, I wish to build upon the notion of powerful representations of Venus and the subversion of gender norms by briefly examining another well-known work by Botticelli: Venus and Mars of c. 1485 (fig. 5).

Figure 5. Sandro Botticelli, Venus and Mars, c. 1485, tempera and oil on poplar panel, 69 cm x 173 cm, National Gallery, London.

Painted around the same time as The Birth of Venus, Venus and Mars depicts the two deities in a post-coital scene. The goddess of love and god of war are often associated with each other in classical, medieval and early modern texts, and Botticelli’s rendition is inspired by this literary tradition.46 The scene, however, does not praise the warrior qualities of Mars; here, he is subdued. Instead, the painting underlines his “volatility and cruelty,” which may only be tamed by his lover, Venus.47 The goddess neutralizes the threat of war, and she does this through her seductive nature, again underlining her power—a power which relies on love, seduction, and sex. In simple terms, if Venus tempers Mars, it is understood that she has a certain power over this virile masculine figure. And so, I argue that Mars is the most vulnerable figure in the painting. He is unclothed and sleeps, while satyrs take hold of his weapon and armour. Meanwhile, Venus watches attentively with full agency and a calm demeanor. She is in complete control, shaping her as an empowered figure.

Most likely commissioned for the marriage of Lucrezia de’ Medici and Jacopo di Giovanni Salviati, the painting demonstrates a certain hierarchical anomaly.48 The bride was a Medici—the most powerful family in Florence—while the groom belonged to a “family of lower social standing” which was “politically compromised” due to their involvement with the Pazzi conspiracy—a major plot aiming to overthrow the Medici which resulted in the death of Lorenzo’s brother, Giuliano de’ Medici.49 This socio-political aspect may help to explain the “complete reversal of the traditional gender roles” seen in the painting, where a clothed female figure looms over a nude male figure.50 This unusual political move thus allowed for such an untraditional painting to be painted. Although the role reversal here may be explained by the social classes of the groom and bride, I argue the painting may nonetheless exhibit a queer nature—a subversion of norms—which is echoed through time and may resonate with future generations for different reasons.The Birth of Venus

Also most likely commissioned as a wedding gift for a member of the Medici family, Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (fig. 6) depicts the goddess Venus with long blond locks standing on a huge scallop shell as she approaches the shore. She is accompanied by secondary figures, who on her left, blow her onto the shore, and to the right, prepare to clothe her. For brevity, I wish to focus my analysis on Venus herself.

Figure 6. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, c. 1485, Tempera on Canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Venus, as the central figure, commands the attention of viewers. She stands in a classical contrapposto pose, balancing on one leg.51 She attempts to cover her breasts with her right hand, and with a handful of her hair in her left, conceals her pubis. The composition is most likely inspired by the writings of Pliny, though the details of the painting are heavily inspired by the Ancient Greek Homeric Hymns in which Aphrodite’s debarkation onto land is described.52 Botticelli likely knew of passages from the Hymns through Angelo Poliziano, the Medici court poet, whose own writings also inspired the artist.53 For example, the gestures and positioning of Venus are not mentioned in these Hymns, yet Botticelli’s painting is strongly reminiscent of Poliziano’s descriptions in Stanze per la giostra:

One could see arising from the waves,

The goddess, clutching her tresses with her right hand,

Her left hand covering her lovely breasts.54

However, here, Botticelli digresses from his textual source. Poliziano clearly writes that Venus covers her breasts with her left hand, but in Botticelli’s painting she uses her right.55 This disparity may be explained by the fact that the artist not only utilized literary sources, but also visual inspirations, most likely a copy of a classical Venus Pudica (as the one seen in fig. 7), which were well known in Tuscany from the fourteenth century onwards.56 It is precisely this intriguing pose on which I wish to further focus my analysis.

Figure 7. Unknown artist, Venus de' Medici, 1st Century BCE, marble (Hellenistic copy of original bronze), 1.53 m, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Venus Podia: On the Origins of the Pose

Art historian George L. Hersey calls the Venus Pudica pose “perhaps the most celebrated bodily stance for female self-presentation in Western art.”57 He notes the implication that goddess has been noticed by the viewer and how she attempts to cover herself yet is “hardly panicked,” shaping her as “paradoxically both chaste and inviting.”58 The Venus in this pose, seen through the eyes of a mammalogist, may be understood as a form of ‘presenting,’ i.e. the act of calling attention to potential mates.59 In fact, Hersey notes the historical origins of this pose, stating it originates from ancient Cypriote figures and refers to images of Ancient Greek hetairai, or prostitutes, where they massage their sexual organs (fig. 8).60

Figure 8. Bronze age Paphiote goddess, Copenhagen, Nationalmuseet.(61)

At some point, there appears to have been a switch from outwardly massaging to simply shielding, which seems to have occurred when the pose slowly became associated with the goddess Aphrodite rather than with sex workers. Hersey wonders whether this switch may be interpreted as “a subtler way of continuing to focus on her reproductive system,” creating a “paradox of modest immodesty.”62 It is precisely this focus on (im)modesty which appears to have made the Venus Pudica a useful pose in Christian imagery.

In the Christian Context

Although an ancient trope, the Venus Pudica appears to have been appropriated by Christian artists at least by the early fourteenth century. Utilizing the pose within the late medieval and early Renaissance Christian context perhaps served to emphasize values of chastity and modesty, as seen in Giovanni Pisano’s c. 1311 rendition in the Cathedral of Pisa (fig. 9).

Figure 9. Giovanni Pisano, pulpit of the Cathedral of Pisa (detail of Venus Pudica type), c. 1311, marble, Cathedral of Pisa, Pisa.

Figure 10. Masaccio, The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, c. 1427, fresco, 208 x 88 cm, Brancacci Chapel, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence.

Figure 11. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (detail), c. 1485, tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Masaccio uses the pose to connote shame. After all, the affect of shame is characterized by the turning of the face or closing of the eyes as a way of halting eye contact with others.64 Notably, it is also characterized by the generalized desire to cover the body from the gaze of the other.65 As she leaves the garden in shame, Eve covers herself in the same way that Venus does (fig 11). However, Eve’s face is drastically different from that of Venus. The former clearly demonstrates an intense feeling of shame. In this sense, we begin to notice precisely how the pose has been used to express very different feelings. With Masaccio’s work, there’s a biblical emphasis on sin. This underlines how the pose has precedents deeply rooted in the affect of shame. In fact, the name Pudica itself comes from the Latin ‘pudendus,’ which can mean both external genitals and “that which is to be ashamed of.”66 It’s also fascinating how only Eve employs this pose; Adam simply covers his face. I would argue there is a clear connection between female sexuality and shame. It is this affect of shame and its associations with female sexuality that may give us insight into the modes in which the Venus Pudica may signify for queer viewers.

Queering the Affect of Shame

Botticelli created several, nearly identical iterations of the Venus Pudica (fig. 12 & 13). As we’ve seen, he gathered inspiration both from classical texts and visual examples. However, he must have surely been exposed to medieval and early Renaissance renditions, as seen in Masaccio’s The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden in Florence or Pisano’s pulpit in nearby Pisa. And yet, it appears that his most significant influence derived from the classical tradition. His Venuses resemble those of antiquity much more than those seen in Christian art.

Figure 12. Sandro Botticelli, Venus (of Turin), c. 1485, 176 cm x 77.2 cm, Sabauda Gallery, Turin.

Figure 13. Sandro Botticelli, Venus (of Berlin), c. 1490, 158.1 cm x 68.5 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

Figures 14 & 15. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (details), c. 1485, tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Figure 16. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (detail), c. 1485, tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

The goddess’ blank expression leaves room for a multitude of readings—even a subtle smile could be read. She could be seen as resisting shame, since shame innately involves the lowering of the head and/or eyes. And if she is indeed smiling, can it be said that she enjoys her position? Regardless of how she is read, she exhibits a certain ambivalence. Sedgwick compares this ambivalence to a child who both hides from a stranger yet peeks through his fingers to see; “In shame I wish to continue to look and to be looked at, but I also do not wish to do so.”68 In connection to her analogy of the child, Sedgwick underlines the intrinsic ties that exist between shame and sexuality, especially during early stages of development.69 It is no coincidence that such a pose became associated with the goddess of love and sex.

Through her ambiguous disposition, I argue that Venus may be read as subverting the notion of shame. She is somewhat of a paradox. She is enigmatic. She is not as distinctly shamed into modesty as her Christian counterparts. The previously examined story of Venus and her lover in the Homeric Hymns perfectly flesh out her dual nature; she inhabits a position between mortal and deity, and between modesty and immodesty. Furthermore, having arrived on land, Venus awaits to be clothed, and clothing itself is speculated to have originated partly to cover up the body from shame.70 Becoming somewhat human rather than simply divine, there becomes a need to cover her human-like flesh. There is thus a straddling of the heavenly and earthly in Botticelli’s oeuvre. Her position outlines a certain malleability or transformation, which I feel is distinctly queer as Venus, here, refuses to be bound by a fixed binary. Through this notion, the goddess may take the role of icon for sexually oppressed people. She can be an inspiration by promoting sexual liberation. After all, shame is directly opposed to pride. And shame has tremendous political potential as it may push oppressed individuals to strive to legitimize their identity and gain rights and protection.71

On the other hand, it can easily be said that by positioning Venus in the Pudica pose—a pose intrinsically tied to shame—Botticelli easily shapes the goddess into an object of consumption for viewers; her shame stands in direct opposition to the act of looking. Instead of gathering agency through her gaze, she is the object to be looked at. Additionally, she appears to avoid the gaze of viewers and instead looks aside. Yet even this is ambiguous. As discussed, Botticelli’s allegorical works are known for being full of ambiguity—for allowing a plethora of different interpretations. And so, perhaps the image of Venus allows for two crucial things. It allows heterosexual male viewers, especially of the nineteenth century, to feel secure about their sexuality and masculinity; they may read her as modest and as a voyeuristic offering. For queer viewers of today, however, she may be read as a symbol of resistance—as a sexually empowered and unapologetic sex icon.

When speaking of viewership, it becomes crucial to view the counterpart of shame, which Sedgwick calls the contempt-disgust affect.72 Notably, the relationship between the two is hierarchical. Shame inhabits the oppressed, and contempt-disgust marks the oppressor.73 If one permits themselves to feel shame—and aspires to please or become like the oppressor—then the hierarchical relationship is maintained.74 I argue that this oppressor/oppressed scheme may be applied to notions of the normative and non-normative, respectively. Transgressing societal norms inherently means risking ostracization, subsequently resulting in shame. Shame, as outlined by Sedgwick, is internalized as a child. What does this mean, then, for a child who, as they grow, progressively transgresses more norms? Although anecdotal, I wish to note my own personal experiences as I deem them highly relevant in the context of shame and the gaze.

As a queer individual, I have become hyperaware of the shame I have internalized as a child. Today, as I walk by men in the street who glare without shame, I purposely question my destined role as object to be gazed at—as a shamed individual, as Venus Pudica, both concealing and revealing my sexuality. Instead of showing such signs of shame—the lowering of the gaze and head—I look directly at these men. I gaze into their eyes. I do not look away. I refuse to. It is a reappropriation of power; if one refuses to be subjugated by the male heteronormative gaze, then its power instantly disintegrates. I have noticed that by replicating their intense gaze, men often react in one of three ways, which may be reduced to notions of 1) disgust, 2) shame, or, most interestingly, 3) increased fascination.

Disgust: They shout slurs and act aggressively, resisting embarrassment by exhibiting the contempt-disgust affect.

Shame: My gaze outlasts theirs, and they cower in shame. Often, however, they attempt to gaze again later, as if to read my expression—to see whether I have become the oppressor or am open to communion. They take on the role of a child peeking through their fingers.

Increased fascination: As with the image of Venus, shame and sexual suggestion may be intertwined. These men interpret my solid gaze as a sexual invitation.

It is perhaps in this last sense that, although being looked at, Venus may gain power over viewers. She may be inviting, yet it is an invitation on her own terms. Although suggestive, she remains in charge of her body. It is in this sense that she may inspire queer viewers and contemporary artists; she demonstrates not only how to navigate shame and other seemingly oppressing positions but empowers the sexually marginalized, and subsequently has become a pop-cultural icon for this reason.

Contemporary Adaptations: Cult of Venus / Cult of Celebrity

Art historian and curator Gabriel Montua has described Botticelli’s figures not only as icons, but as “quintessences of Western art.”75 In her very essence, the figure of Venus has always been part of a cult. In Ancient Greece and Rome, she played the role of deity. In the Renaissance, she took on a key role in a cult of beauty. It is even thought that Botticelli instilled within his Venus the image of Simonetta Vespucci—a beautiful Florentine woman who died tragically young.76 Quoted as being even more beautiful in death, Vespucci achieved celebrity status in her day—one which may be equated, in certain senses, to modern celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe. Today, the aura of Venus—having inhabited countless sexually empowered women—lives on in appropriations by contemporary artists. It is thus from these two aforementioned blonde icons that I wish to examine a third: Lady Gaga.

Lady Gaga as Venus: A Case Study

Before exploring her appropriations of the image of Venus, I wish to lay out the foundations as to why Lady Gaga became an icon for young queer individuals. Having received twelve Grammy Awards, Gaga is undoubtedly a successful mainstream artist. However, she has always engaged in underground themes of sexual empowerment and has been a leading figure in LGBT advocacy. She is, and will always be, the queen of the queers.

Gaga as Queen of the Queers

In the early stages of her career, Lady Gaga was met with the rumor that she was a “hermaphrodite.”77 However, when asked countless times in interviews whether she possesses male genitalia, Gaga does not cower in shame; she makes fun of the rumours, allowing herself to take power over the situation. By refusing to give a straight and serious answer, she does not grant satisfaction to the interviewer and to the public at large. These instances may have been defining moments in shaping her as a gay icon, as sociologist Mathieu Deflem states: “Lady Gaga ultimately rejects conventional sex appeal. Toying with rumors about her sex and sexual orientation, she both understands the gendered dynamics of the world of popular music and uses them to her advantage.”78 In this sense, Gaga may be understood as camping femininity and traditional sex appeal; she utilizes humour and theatricality to question cultural conceptions of gender and sex and thus “opens up mainstream cultural production to queer readings.”79 Lady Gaga’s Camp aesthetics—from her outrageous costumes to her more subtle tongue-in-cheek comments—allows room for queer humour, and thus queer pleasure, while also allowing for a “serious critique of hegemonic discourses that oppress alternative models of meaning-making.”80 For instance, Gaga parodies femininity; she points out its oppressive aspects and the male gaze, ridiculing the heteronormative constructs of gender and sexuality.81 In particular, I argue that her self-fashioning into the goddess Venus—the epitome of constructed femininity—communicates exactly that.

“Judas”: “In the most biblical sense, I am beyond repentance”

Gaga makes her first allusions to Venus in her 2011 music video for “Judas,” which she pairs with a plethora of biblical references. Most notably, she puts Venus into contrast with Mary Magdalene, calling attention to the binaries of the sacred and profane. I wish to briefly examine key frames to further support my argument. Gaga appears as Mary Magdalene, washing the feet of Jesus and Judas (fig. 17). However, within a split second, the shot immediately switches to a scene of Gaga standing on a rocky shore, with waves threatening to strike her (fig. 18).

Figures 17 & 18. Stills from: Lady Gaga, Judas, directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2011).

The latter image is undoubtedly a reference to Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus.82 However, Botticelli’s rendition—from its pale colours to its streaks of gold leaf—is put into stark contrast with Gaga’s interpretation in cold and dark colours.83 Additionally, Gaga is positioned on a dangerous rocky cliff, “which threatens to collapse under a forceful rush of water,” whereas Venus is perched on a giant seashell, “in classical antiquity a metaphor for the female vulva.”84 The reference, but also the critique of classical femininity, is made evident. The shot then continues to switch back and forth between the two scenes—between Gaga as Mary Magdalene and Gaga as Venus—and the two begin to merge. Even as in the scene of Mary Magdalene, the frame’s composition points to The Birth of Venus (fig. 19 & 20). Venus is positioned between other mythological figures and rests on a seashell, whereas Gaga—with her similar long blond locks—inhabits the space between Jesus and Judas and rests within a tub of water.

Figures 19 & 20. Stills from: Lady Gaga, Judas, directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2011).

In brief, Gaga plays not only with traditional femininity, but with notions of purity and modesty so often associated with ideal women. She takes the role of femme fatale and makes “genderplay her boldest intention” by subversively teasing the male viewer.85 In other words, by parodying femininity through hyperbole, Gaga portrays two iconic female figures and destabilizes their classical conceptions.86 Notably by embodying the figure of Venus, Gaga becomes a sex object, but she does so on her own terms; she utilizes the idea of becoming a sex object to challenge exactly what that could mean.87 And, two years after the release of “Judas,” from her empowering album Born This Way, Gaga continues her self-fashioning into Venus for her 2013 album ARTPOP.

ARTPOP: Self-Fashioning Into The Goddess of Love

Comparatively speaking to her previous album, ARTPOP was poorly received. However, having been described as being ahead of its time, the album has recently gained attention once again. Being fourteen years old at the time of its release, the album was crucial in the development of my own identity, and as my most listened to album by far, it is clear that ARTPOP shaped my queer persona. In this era, Gaga makes extensive references to Antiquity and the Renaissance, often specifically to Venus and Aphrodite. She even changed her name on twitter to “Goddess of Love” during this time—clearly outlining her self-fashioning into Venus. Additionally, her empowering twitter bio read: “You are a legend. Make a sculpture of you. Self-invention matters. You are the artist of your own life. Hashtag Artpop.”88 Appropriately, Gaga fashioned all aspects of her life as if she was the goddess herself, arriving at airports in the Venus Pudica pose (fig. 21).

Figure 21. Lady Gaga arriving in Athens, 2014.

Gaga’s intentions here are clear. Without a doubt, she fashions herself into Venus. And so, what exactly could it mean for the ‘queen of the queers’ to self-fashion into the goddess of love and sex? This question may reveal precisely how the aura of Venus, perpetuated through the pop icon, may symbolize an important form of sexual emancipation for queer audiences. The album cover itself helps shed light on this notion (fig. 22).

Figure 22. Lady Gaga, ARTPOP, Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013.

Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, paired with Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne, is used as the background for the cover, underlining the artist’s connections with Venus. The figure of Gaga, here, is a sculpture by contemporary artist Jeff Koons. I suggest the sculpture may be read as a variation of the Venus Pudica pose, as Gaga’s breasts and pubis are covered. However, she grasps both of her breasts firmly and gazes into the eyes of the viewer. Her legs are spread open in a sexually inviting manner. However, her pubis is covered by a shiny blue sphere, which reflects back at us and calls attention to our viewership. Gaga and Koons appear to directly reference the push and pull dynamics of The Birth of Venus; Gaga, too, is both sexually suggestive yet protective of herself. There thus exists an even deeper level of subversion at play here.

Furthermore, throughout the aesthetics of ARTPOP, Gaga positions herself as what Nathalie Weidhase and Poppy Wilde call “the posthuman.” They describe the concept in depth:

The posthuman is not a singular, static, autonomous individual, but a subjectivity that is emergent…Posthuman theory consequently troubles dualistic binaries, such as those between male/female, self/other, subject/object, and human/machine/animal. This allows for a critique [of] anthropocentric hierarchies, instead arguing for a rhizomatic acknowledgement of the different entities in the subjectivities that emerge.89

By fashioning herself into artworks, objects and even animals in ARTPOP, Gaga embodies the posthuman.90 The posthuman, I argue, may be understood as distinctly queer. It resists binaries and questions hegemonic conceptions of identity: “Queer studies and posthumanism therefore both question the ideological roots behind many of our taken for granted assumptions.”91 Gaga further comments on notions of the binary in scientific terms, stating:

Know only that you must acknowledge the difference between the two and disregard it. In essence your brain must relearn the concept of ‘three’: Not one or the other (two) but both and neither.… [I]solate binary and all quantitative processing as incorrect and harmful to any advanced operational systems… you are standing on the brink of breaking the cycle... this reality has been recycling itself... remixing over and over the same timelines with varying yet identical outcomes. ARTPOP, then, is the unification of the back-and-forth dialogue formed as a result of a voice talking to its own entity... united across time and space to express a singular message.92

Therefore, Gaga explicitly implores us to forget our preconceived notions about the binary—about everything once taken as fact. She takes us on an audio-visual journey of self-discovery—one which I want to deconstruct, focusing on a few key songs in the album.

“ARTPOP”: “My artpop could mean anything”

The title track of the album, positioned precisely in its middle, brings together the main message of the work. Gaga, in lyrical form, expresses notions of queer, stating: “My ARTPOP could mean anything.” In a strikingly similar fashion to Botticelli’s allegorical works, Gaga’s album, as she stresses, is up for a multitude of interpretations. Her work is not defined by any binary; it is not one thing or another, but rather exists within a spectrum of meaning. Again, in a manner similar to Botticelli, this is precisely how an artist manages to fascinate, shock and inspire the masses. The similarities do not end there, as Gaga begins the song with these lyrics:

Come to me

In all your glamour and cruelty

Just do that thing that you do

And I'll undress you.94

These lines immediately bring to mind Botticelli’s Mars and Venus. Gaga, as Venus, seduces her male counterpart in his glamour (regalia) and cruelty (war), and she undresses him. The parallels are unmistakably clear, and by making such allusions, Gaga shapes herself as a sexually empowered female figure and allows her fans to do the same. In fact, she directly points out her cult status, which she equates with that of Venus.

“Applause” & “Aura”: Calling Attention to the Construction of the Self

In the opener, “Aura,” Gaga calls attention to her enigmatic status: “Do you wanna see the girl who lives behind the aura?”95 Intentionally or not, she makes connections to Benjamin’s understanding of the aura, which he appropriately uses the figure of Venus to describe. In an over-the-top, camp fashion, Gaga points out her position. She becomes self-referential. And, in “Applause,” this notion continues: “One second I'm a Koons, then suddenly the Koons is me. Pop culture was in art, now art’s in pop culture, in me.”96 Gaga bridges the gap between art and pop-culture, between self and other, and in a reverse-Warholian manner, deconstructs it all. She is both pop-culture and art, and she is also neither. She is posthuman. Venus is no longer just art. She is also a pop-cultural icon. Further connections to the goddess are made in the music video for “Applause.” Gaga makes direct allusions to The Birth of Venus, as made evident by her seashell bra and earrings (fig. 23).

Figure 23. Still from: Lady Gaga, Applause, directed by Inez and Vinoodh (USA: Interscope Records, 2013).

Here, Gaga becomes a postmodern rendition of the goddess. However, she positions her arms as if she were an athlete, or a bodybuilder. She further subverts femininity as there exists a certain traditional masculinity associated with such a pose. And so, by fashioning herself as Aphrodite, Gaga acknowledges her celebrity status and her cult following, stating: “Give me that thing that I love. Put your hands up, make ‘em touch.” She calls attention to her fame, positioning herself as the Greco-Roman goddess and positioning her fans as worshippers, thus creating a quasi-religion for the marginalized.

“G.U.Y.”: The Girl Under You Has More Power Than You Think

To elaborate on her role as inspiration for the sexually oppressed, I wish to lastly examine Gaga’s song “G.U.Y.” and its accompanying short film. In the film, the song “ARTPOP” first plays as Gaga portrays a fallen angel, with an arrow pierced through her chest. She’s transported to a lavish castle, and takes the role of martyr, alluding to the crucifixion (fig. 24). Then, the song “Venus” begins as Gaga is given new life; she is submerged in water and is reborn (fig. 25).

Figures 24 & 25. Stills from: Lady Gaga, G.U.Y. (An ARTPOP Film), directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2014).

Suddenly, “G.U.Y.” comes on and Gaga becomes an incredibly powerful figure—an unapologetic sex icon. She not only references cupid’s bow to underline her seductive powers (fig. 26) but again, she positions herself with images of seashells and utilizes her long platinum blonde hair to become this sort of postmodern Venus—caught between pop culture and art (fig. 27).

Figure 26. Still from: Lady Gaga, G.U.Y. (An ARTPOP Film), directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2014).

Figure 27. Still from: Lady Gaga, G.U.Y. (An ARTPOP Film), directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2014).

The song’s lyrics push the message of sexual emancipation even further. It begins with the lines, “Greetings Himeros, God of sexual desire, son of Aphrodite, lay back, and feast as this audio guides you through new and exciting positions.”98 Immediately, she lays out the premise. Just like in the myth of Aphrodite in the Homeric Hymns, Gaga takes on the active sexual role. She pursues. She pleases—on her own terms. There is a certain power in being submissive that is taking shape here, as Gaga sings: “I don’t need to be on top to know I’m worth it, ‘cause I'm strong enough to know the truth.”99 The truth is, she is in power, even in her submissive role. “G.U.Y.” itself stands for “Girl Under You.” Gaga subverts traditional notions of sex as again, she sings: “I'm gonna wear the tie, want the power to leave you. I'm aiming for full control of this love. I wanna be that GUY, the girl under you.”100

In this short film, Gaga takes us on a ride filled with references to pop-culture and art, and it is a journey that emphasizes revival, strength, and sexual freedom. She takes on a performative and theatrical role throughout—a role which may remind queer viewers of their own journey. Gaga first portrays a vulnerable, martyrized character. However, she is reborn as a goddess—one in complete control of her sexuality. She refuses to be shamed, instead making her desires and submissive powers explicitly clear. The connections to queer lived experiences are evident, and if it wasn’t clear enough, she gazes into the eyes of viewers, both seducing the heterosexual male and overpowering his gaze, while also reminding the queer viewer of the exclusive Camp clique that they are a part of (fig. 28 & 29).

Figure 28. Still from: Lady Gaga, G.U.Y. (An ARTPOP Film), directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2014).

Figure 29. Still from: Lady Gaga, G.U.Y. (An ARTPOP Film), directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2014).

And so, by employing the image of Venus, which she combines with lyrics about sexual subversion and empowerment, I think Gaga makes one thing clear: The image of Venus is incredibly powerful and rich with meaning, and it may be used to empower the sexually marginalized.

Conclusion

Throughout this research paper, I have performed several things. I have deconstructed gender and sexuality as we know it today. Also, I have observed exactly how gender and sexuality were viewed at the time that Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus was painted, bridging a gap and offering an alternative model of understanding. I have examined both the visual and literary development of the goddess of love and sex, as well as her representations in Botticelli’s works. Specifically, I analyzed the affect of shame, which proved crucial in creating parallels with queer lived experiences. Lastly, by exploring contemporary appropriations by Lady Gaga, I solidified my argument: The figure of Venus, as paradoxical icon, may be understood as a symbol of sexual—and thus societal emancipation for oppressed individuals. Venus and Gaga (through her embodiment of the goddess) may be understood as pop-cultural icons playing a crucial role in empowering the marginalized through shameless demonstrations of sexuality.

And so, where does this all leave us? And what does this all mean for someone like me—a little queer kid from a small town? Gaga, through her appropriation of Venus, allowed me to shape my own identity. This self-fashioning has allowed me to overcome the shame that developed in my early years, and as Sally Munt puts it perfectly, “Thinking about shame over the past 15 years was not so much an intellectual choice as a survival strategy.”101 And again, shame, sex, love, and the gaze remain intrinsically tied:

We may then not look too closely at each other, because we cannot be sure how we might feel if we were to do so. Indeed, many of us fall in love with those into whose eyes we have permitted ourselves to look and by whose eyes we have let ourselves be seen. This love is romantic because it is continuous with the period before the individual lovers knew shame. They not only return to baby talk, but even more important they return to baby looking.102

In the end, this is a quest for love and self-acceptance. It is empowering to look, and it may also be empowering to be looked at. Giving into the gaze can be an incredibly cathartic experience, reminding ourselves what love feels like. It can mean both reclaiming the power to look—the refusal to be shamed—and can signify a redefining of what it means to be looked at. It is thus no wonder that the goddess of love and sex signifies so intensely for queer individuals. Botticelli’s Venus, in this sense, allows herself to be seen. However, through her gestures, she takes the necessary steps to signal that she possesses agency over her body. At a distance, we may thus fall in love with her. In this way, by subsequently looking within, may we not fall in love with ourselves?

I have looked within, and “I wonder if this could be love.”103

Endnotes

Karl Whittington, “QUEER,” Studies in Iconography 33 (2012): 157.

Whittington, “QUEER,” 157.

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Tendencies (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 8.

Whittington, “QUEER,” 157.

Judith Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” in Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology, ed. Donald Preziosi (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 356.

Butler, 362.

Butler, 360.

Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution,” 364.

Butler, “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution,” 363.

Susan Sontag, Notes on Camp (London, England: Penguin Classics, 2018), 1.

Sontag, 4.

Thomas Walter Laqueur, Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1992), 22.

Laqueur, Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud, 124.

Laqueur, Making Sex, 124.

Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 87.

Rocke, 88.

Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence, 88.

Rocke, 88-89.

Rocke, 102.

Rocke, 102.

From the Oxford English Dictionary.

Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence, 198.

Rocke, 200.

Rocke, 201.

Adrian W. B. Randolph, Engaging Symbols: Gender, Politics, and Public Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 140.

Randolph, Engaging Symbols: Gender, Politics, and Public Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence, 141.

Randolph, 142.

Randolph, 169.

Randolph, 170.

Randolph, Engaging Symbols: Gender, Politics, and Public Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence, 171.

Randolph, 171-172.

Randolph, Engaging Symbols: Gender, Politics, and Public Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence, 172.

Randolph, 183-84.

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility,” in The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology, ed. Donald Preziosi (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 439.

Barbara M. Breitenberger, Aphrodite and Eros: The Development of Erotic Mythology in Early Greek Poetry and Cult (New York: Routledge, 2007), 7-8.

Breitenberger, 8.

Breitenberger, Aphrodite and Eros, 12.

Breitenberger, 12.

Breitenberger, 15.

Breitenberger, 21.

Breitenberger, 23.

Breitenberger, Aphrodite and Eros, 47.

Breitenberger, 51.

Breitenberger, 26.

Frank Zöllner, Botticelli (Munich: Prestel, 2005), 135.

Frank Zöllner, Botticelli (Munich: Prestel, 2005), 125.

Zöllner, 125.

Frank Zöllner, Botticelli (Munich: Prestel, 2005), 130.

Zöllner, 130.

Zöllner, 130.

Frank Zöllner, Botticelli (Munich: Prestel, 2005), 135.

Zöllner, 135.

Zöllner, 135-36.

1.101.1-3 as found in Frank Zöllner, Botticelli (Munich: Prestel, 2005), 136.

Zöllner, 136.

Zöllner, 136.

George L. Hersey, The Evolution of Allure: Sexual Selection from the Medici Venus to the Incredible Hulk (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996), XII.

Hersey, XII.

Hersey, XII.

Hersey, XIII-XIV.

As seen in Hersey, XIII-XIV. Date unknown.

Hersey, XIII-XIV.

Jacqueline E. Jung, “The Choir Screen as Partition,” in The Gothic Screen: Space, Sculpture, and Community in the Cathedrals of France and Germany, ca. 1200-1400 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 18.

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Adam Frank, and Irving E. Alexander, Shame and Its Sisters: A Silvan Tomkins Reader (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995), 134.

Sedgwick, Frank, and Alexander, 134.

Oxford English Dictionary.

Sedgwick, Frank, and Alexander, Shame and Its Sisters, 133.

Sedgwick, Frank, and Alexander, Shame and Its Sisters, 137.

Sedgwick, Frank, and Alexander, 173.

Sedgwick, Frank, and Alexander, Shame and Its Sisters, 134.

Sally Munt, Queer Attachments: The Cultural Politics of Shame (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2008), 4.

Sedgwick, Frank, and Alexander, Shame and Its Sisters, 139.

Sedgwick, Frank, and Alexander, 139.

Sedgwick, Frank, and Alexander, 139.

Gabriel Montua, “Giving an Edge to the Beautiful Line: Botticelli Referenced in the Works of Contemporary Artists to Address Issues of Gender and Global Politics,” in Botticelli Past and Present, ed. Ana Debenedetti and Caroline Elam (London, UCL Press, 2019), 290.

Hans Körner, “Simonetta Vespucci: The Construction, Deconstruction, and Reconstruction of a Myth,” in Botticelli: Likeness, Myth, Devotion, ed. Andreas Schumacher (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2009), 61.

Mathieu Deflem, “The Sex of Lady Gaga,” in The Performance Identities of Lady Gaga: Critical Essays, ed. Richard J. Gray (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2012), 25.

Deflem, “The Sex of Lady Gaga,” 32.

Katrin Horn, “Follow the Glitter Way: Lady Gaga and Camp,” in The Performance Identities of Lady Gaga: Critical Essays, ed. Richard J. Gray (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2012), 87.

Horn, 104.

Stan Hawkins, “‘I’ll Bring You Down, Down, Down’ Lady Gaga’s Performance in ‘Judas,” in Lady Gaga and Popular Music: Performing Gender, Fashion, and Culture, ed. Martin Iddon and Melanie L Marshall (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014), 16.

Hawkins, “‘I’ll Bring You Down, Down, Down’ Lady Gaga’s Performance in ‘Judas,” 14.

Hawkins, 14.

Hawkins, 14.

Hawkins, “‘I’ll Bring You Down, Down, Down’ Lady Gaga’s Performance in ‘Judas,” 16.

Gray, and Anusha Rutnam, “Her Own Real Thing: Lady Gaga and the Haus of Fashion,” in Lady Gaga and Popular Music: Performing Gender, Fashion, and Culture, ed. Martin Iddon and Melanie L Marshall (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014), 52.

Paul Hegarty, “Lady Gaga and the Drop: Eroticism High and Low,” in Lady Gaga and Popular Music: Performing Gender, Fashion, and Culture, ed. Martin Iddon and Melanie L Marshall (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014), 84.

From Twitter archives.

Nathalie Weidhase and Poppy Wilde, “‘Art’s in Pop Culture in Me’: Posthuman Performance and Authorship in Lady Gaga’s Artpop (2013),” Queer Studies in Media & Popular Culture 5, no. 2-3 (2020): 239.

Weidhase and Wilde, 239.

Weidhase and Wilde, 241.

Lady Gaga, Thoughtrave: An Interdimensional Conversation with Lady Gaga, interview by Robert Craig Baum (Brooklyn, New York: Punctum Books, 2016), 32.

Lady Gaga, “ARTPOP,” track 8 on ARTPOP, Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013.

Lady Gaga, “ARTPOP.”

Lady Gaga, “Aura,” track 1 on ARTPOP, Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013.

Lady Gaga, “Applause,” track 15 on ARTPOP, Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013.

Lady Gaga, “Applause.”

Lady Gaga, “G.U.Y.,” track 3 on ARTPOP, Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013.

Lady Gaga, “G.U.Y.”

Lady Gaga, “G.U.Y.”

Munt, Queer Attachments, 1.

Sedgwick, Frank, and Alexander, Shame and Its Sisters, 147.

Lady Gaga, “Venus,” track 2 on ARTPOP. Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013.

Bibliography

Acidini, Christina. “For a Prosperous Florence: Botticelli’s Mythological Allegories.” In Botticelli: Likeness, Myth, Devotion, edited by Andreas Schumacher, 73-92. Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2009.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility.” In The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology, edited by Donald Preziosi, 435-442. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Breitenberger, Barbara M. Aphrodite and Eros: The Development of Erotic Mythology in Early Greek Poetry and Cult. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory” In Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology, edited by Donald Preziosi, 356-366. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Deflem, Mathieu. “The Sex of Lady Gaga.” In The Performance Identities of Lady Gaga: Critical Essays, edited by Richard J. Gray, 19-32. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2012.

Gray, Sally, and Anusha Rutnam. “Her Own Real Thing: Lady Gaga and the Haus of Fashion.” In Lady Gaga and Popular Music: Performing Gender, Fashion, and Culture, edited by Martin Iddon and Melanie L Marshall, 44-66. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014.

Hawkins, Stan. “‘I’ll Bring You Down, Down, Down’ Lady Gaga’s Performance in

‘Judas.’” In Lady Gaga and Popular Music: Performing Gender, Fashion, and Culture, edited by Martin Iddon and Melanie L Marshall, 9-26. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014.

Hegarty, Paul. “Lady Gaga and the Drop: Eroticism High and Low.” In Lady Gaga and Popular Music: Performing Gender, Fashion, and Culture, edited by Martin Iddon and Melanie L Marshall, 82-93. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014.

Hersey, George L. The Evolution of Allure: Sexual Selection from the Medici Venus to the Incredible Hulk. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996.

Horn, Katrin. “Follow the Glitter Way: Lady Gaga and Camp.” In The Performance Identities of Lady Gaga: Critical Essays, edited by Richard J. Gray, 85-106. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2012.

Iddon, Martin, and Melanie L Marshall. “Introduction.” In Lady Gaga and Popular Music: Performing Gender, Fashion, and Culture, 1-8. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014.

Jung, Jacqueline E. “The Choir Screen as Partition.” In The Gothic Screen: Space, Sculpture, and Community in the Cathedrals of France and Germany, ca. 1200-1400, 11-43. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Körner, Hans. “Simonetta Vespucci: The Construction, Deconstruction, and Reconstruction of a Myth.” In Botticelli: Likeness, Myth, Devotion, edited by Andreas Schumacher, 57-72. Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2009.

Lady Gaga, “Applause.” Track 15 on ARTPOP. Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013.

Lady Gaga, “ARTPOP.” Track 8 on ARTPOP. Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013.

Lady Gaga, “Aura.” Track 1 on ARTPOP. Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013.

Lady Gaga, “G.U.Y.” Track 3 on ARTPOP. Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013.

Lady Gaga. Thoughtrave: An Interdimensional Conversation with Lady Gaga. Interview by Robert Craig Baum. Brooklyn, New York: Punctum Books, 2016.

Lady Gaga, “Venus.” Track 2 on ARTPOP. Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013.

Laqueur, Thomas Walter. Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Montua, Gabriel. “Giving an Edge to the Beautiful Line: Botticelli Referenced in the Works of Contemporary Artists to Address Issues of Gender and Global Politics.” In Botticelli Past and Present, edited by Ana Debenedetti and Caroline Elam, 290–306. London: UCL Press, 2019.

Munt, Sally. Queer Attachments: The Cultural Politics of Shame. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2008.

Randolph, Adrian W. B. Engaging Symbols: Gender, Politics, and Public Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002.

Rocke, Michael. Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Tendencies. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky, Adam Frank, and Irving E Alexander. Shame and Its Sisters: A Silvan Tomkins Reader. Durham: Duke University Press, 1995.

Sontag, Susan. Notes on Camp. London, England: Penguin Classics, 2018.

Weidhase, Nathalie, and Poppy Wilde. “‘Art’s in Pop Culture in Me’: Posthuman Performance and Authorship in Lady Gaga’s Artpop (2013).” Queer Studies in Media & Popular Culture 5, no. 2-3 (2020): 239–57.

Whittington, Karl. “QUEER.” Studies in Iconography 33 (2012): 157-68. Zöllner, Frank. Botticelli. Munich: Prestel, 2005.

Images

Figure 1. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, c. 1485, Tempera on Canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Figure 2. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (detail), c. 1485, tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Figure 3. Donatello, David, c. 1440s, bronze, 158 cm, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

Figure 4. Back view of Donatello’s David, c. 1440s, bronze, 158 cm, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

Figure 5. Sandro Botticelli, Venus and Mars, c. 1485, tempera and oil on poplar panel, 69 cm x 173 cm, National Gallery, London.

Figure 6. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, c. 1485, Tempera on Canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Figure 7. Unknown artist, Venus de’ Medici, 1st Century BCE, marble (Hellenistic copy of original bronze), 1.53 m, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Figure 8. Bronze age Paphiote goddess, Copenhagen, Nationalmuseet.

Figure 9. Giovanni Pisano, pulpit of the Cathedral of Pisa (detail of Venus Pudica type), c. 1311, marble, Cathedral of Pisa, Pisa.

Figure 10. Masaccio, The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, c. 1427, fresco, 208 x 88 cm, Brancacci Chapel, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence.

Figure 11. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (detail), c. 1485, tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Figure 12. Sandro Botticelli, Venus (of Turin), c. 1485, 176 cm x 77.2 cm, Sabauda Gallery, Turin.

Figure 13. Sandro Botticelli, Venus (of Berlin), c. 1490, 158.1 cm x 68.5 cm, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

Figure 14. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (detail), c. 1485, tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Figure 15. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (detail), c. 1485, tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Figure 16. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (detail), c. 1485, tempera on canvas, 172.5 x 278.5 cm, Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

Figure 17. Still from: Lady Gaga, Judas, directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2011).

Figure 18. Still from: Lady Gaga, Judas, directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2011).

Figure 19. Still from: Lady Gaga, Judas, directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2011).

Figure 20. Still from: Lady Gaga, Judas, directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2011).

Figure 21. Lady Gaga arriving in Athens, 2014.

Figure 22. Lady Gaga, ARTPOP, Streamline and Interscope Records, 2013.

Figure 23. Still from: Lady Gaga, Applause, directed by Inez and Vinoodh (USA: Interscope Records, 2013).

Figure 24. Still from: Lady Gaga, G.U.Y. (An ARTPOP Film), directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2014).

Figure 25. Still from: Lady Gaga, G.U.Y. (An ARTPOP Film), directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2014).

Figure 26. Still from: Lady Gaga, G.U.Y. (An ARTPOP Film), directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2014).

Figure 27. Still from: Lady Gaga, G.U.Y. (An ARTPOP Film), directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2014).

Figure 28. Still from: Lady Gaga, G.U.Y. (An ARTPOP Film), directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2014).

Figure 29. Still from: Lady Gaga, G.U.Y. (An ARTPOP Film), directed by Lady Gaga (USA: Interscope Records, 2014).