Looming Large: Coverlet Weaving in Southern Appalachia

Written by Madeleine Mitchell

Edited by Sam Lirette

Introduction

In this essay I am dealing with coverlet weavings from the Southern Appalachian region of the United States, specifically during the Craft Revival of the early 20th century. I will argue that my chosen topic has diverse feminist, economic, and artistic implications which give it a rich background for art historical reading. To execute this reading, I will first give a history of the region, the Craft Revival, and its key figures. I will then examine the social and economic structures weaving occupied in this setting. This context will help formulate a model for assessing coverlets as art in order to argue for their consideration in the art historical scope.

Figure 1. John C. Campbell, Map of Southern Appalachia, John C. Campbell Foundation, https://artsandsciences.sc.edu/appalachianenglish/node/783.

Geography and Cultural History

Allen Eaton defines the Southern Highlands or Southern Appalachia as “the western strip of Maryland, the Blue Ridge and Alleghany Ridge counties of Virginia, nearly all of West Virginia, eastern Kentucky and eastern Tennessee, western North Carolina, the counties of northwestern South Carolina, northern Georgia, and northeastern Alabama.”1 I include this detailed definition to emphasize how large and diverse of a region we are dealing with when we say Southern Appalachia. The mountains in this area are specifically known as the Blue Ridge Mountains for the blue haze which covers them when seen from a distance. This area is a distinct region of the United States which is often treated as a backwater. This is due to the isolation which comes with the difficult terrain of the Blue Ridge Mountains, which contain Mount Mitchell, the highest peak east of the Mississippi River. The area is largely avoided by migration paths, with most early American pioneers choosing to take the Cumberland Gap or travel all the way to Georgia to avoid the mountains altogether. The impassability caused people who did settle in the region to experience great isolation. This led to a consistent othering of these people in discussions of subcultures within America.2

Figure 2. Image of Blue Ridge Mountains https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Ridge_Mountains#/media/File:Rainy_Blue_Ridge-27527.jpg.

While this remoteness created many practical difficulties and required a very self-sufficient lifestyle, it also gave the region a distinct cultural identity which lingers into the 21st century. This culture is perhaps most famous for its Appalachian music with its distinctive fiddle, banjo, and dulcimer.3 Probably most akin to folk music with roots in Scotland and Africa, Appalachian music was a major influence on rock n’ roll, bluegrass, and country. At the same time as the Craft Revival, there was a folk revival focusing on Appalachian music.4 This revival culture was due to the lack of documentation which comes with oral traditions passed through generations. With the increased access to the outside world, younger generations lost the desire and need to learn from their elders, therefore cultural recording projects saved much Appalachian cultural history.5 The region also has a history of square dance and clogging, as well as a rich storytelling and folklore tradition which was not yet widely recorded at the time of the Craft Revival.6 Decades of these rural traditions were disrupted, like most everything else, by the greatest loss of lives ever seen on American soil.7

The American Civil War left a path of destruction from Pennsylvania to Georgia.8 However, it also brought a wave of industrialization to previously homespun southern areas. In the rural reaches of the Appalachian mountains, new goods became accessible.9 While this created a new ease of life and room for economic growth, it also drastically damaged the culture of handicrafts from the region. Alvic states, “after the Civil War, looms were idle and were stored in barns.”10 Crafts including weaving, woodworking, and pottery were slowly lost. Practitioners gradually died without passing on their knowledge. Alvic cites a unique source written by Jake Carpenter of Three Mile Creek, North Carolina. He noted the death of community members along with their occupations from 1841 to 1916. The last noted as a weaver and spinner died in 1896. In the last 20 years of his records, Carpenter noted no weavers.11 This primary evidence suggests that by the 1890s, the distinct craft of coverlet weaving, which is the focus of this paper, was all but lost.

The Southern Appalachian Handicraft Revival

The saving grace of weaving and handicrafts was the Southern Appalachian Craft Revival. Started around Berea, Kentucky and Asheville, North Carolina, the Craft Revival was not a cohesive or particularly intentional movement.12 In fact, it can only be called a movement in retrospect. Rather, it was the result of various individuals who saw value in saving these crafts, and it all serendipitously happened at the same time. The revival took two distinct forms based on Allanstand in North Carolina and Berea in Kentucky: craft groups/guilds that brought together artists who worked in their homes and organized schools where craft was taught and created. It revived knowledge of local craft in Appalachian people and created income by marketing goods to northern audiences. There are multiple figures cited as the founders of the Craft Revival. There is Dr. William Frost from Berea College in Kentucky,13 Lucy Morgan from the Penland Weavers, 14 and Olive Campbell and her husband John.15 However, the most referenced name is Frances L. Goodrich, a missionary from the north who saw the chance to create change through art.16 While the specific founder is not necessarily important, it is significant that the majority of leaders named are women. With the exception of Dr. Frost, the Craft Revival was spearheaded by women. From the start this movement was female-driven with the focus of bettering women’s lives.

Figure 3. Frances L. Goodrich, https://www.wcu.edu/library/DigitalCollections/CraftRevival/people/franceslgoodrich.html.

Allanstand Cottage Industries, founded by Frances L. Goodrich, was based on Goodrich’s desire to bring “healthful excitement” to the isolated women of the area around Asheville, North Carolina.17 Goodrich, like many other cottage weaving group founders, was a religious missionary who came to the region to help local residents. She came from a well-educated northern family; her great grandfather, Noah Webster, wrote the first American dictionary.18

Goodrich found an interested market in the Northern states for Appalachian coverlets and decided to embrace weaving as a means of social and economic opportunity for women.19 She did so in conjunction with Susan Chester Lyman, who brokered orders from northern consumers and brought the commissions to mountain weavers.20 Unlike Berea which functioned in a centralized location, Allanstand’s weavers all worked from home. They met regularly to discuss weaving and form social connections. Allanstand was taken over by the Southern Highland Craft Guild in 1931 and still works under this name now.21 I was able to visit this institution and see the sample book belonging to Frances L. Goodrich (fig. 9), the comprehensive nature of which speaks to her thorough dedication to the Craft Revival.

Berea College still functions today much like it did in the early 20th century. It was the first model for centralizing craft organizations in a similar manner to traditional colleges.22 In 1893, the new president of the school, Dr. Frost, took a tour of the surrounding area and came to love the traditional weaving he saw on his travels.23 His love of these coverlet weaving eventually led to a barter system in which he accepted coverlets in exchange for a portion of tuition fees at Berea.24 The college went on to start a weaving workshop, host homespun craft fairs where students could make profits, and establish its famous fireside industries.25 Like Goodrich, Frost found there was a sustained demand for these weaving in the north where home spinning and weaving were far less practiced.26 This commercial potential of coverlet weavings colored the entire Craft Revival and took it beyond cultural movement to major artistic moment.

In the early 20th century across the region, various groups of weavers organized around the craft following the ideas of Goodrich and Frost. Eaton lists thirty organizations formed from 1901 through the 1930s.27 These groups along with the Southern Industrial Education Association, Russell Sage Foundation, Conference of Southern Mountain Workers, and the Southern Highland Craft Guild created the Craft Revival. The Southern Industrial Education Association was created to help women and children struggling after the Civil War by teaching them practical skills.28 The Russell Sage Foundation was created for the betterment of living conditions in the United States.29 In the southern division, this broad mission took the form of economic investment in local crafts. Allen Eaton, the author of my major historical source, worked for the foundation. The Russell Sage Foundation also prompted the formation of the Conference of Southern Mountain Workers, where the usually disconnected people working in isolation had the chance to connect and learn from each other.30 One meeting spurred the creation of the Southern Highland Craft Guild, which still functions today in Asheville, North Carolina.31 These organizations promoted the educational and economic betterment of rural women through weaving and contributed immensely to the Craft Revival. All of the phenomena which undergird my argument were made possible by these people and organizations.

Argument and Source Summary

Having established the cultural settings and the multifaceted nature of the Southern Appalachian Handicraft Revival, I will delve into my three primary objectives. The first is to illuminate the female community building that weaving spurred. Second, I will look at the complex economic and cultural implications of the Craft Revival within and outside of Southern Appalachia. Third, I will advocate for the aesthetic, art historical consideration of coverlet weaving. In the resources on coverlet weaving, there is a gap in art historical analysis beyond talk of color and pattern choices. I will try to fill this gap and argue for the consideration of Appalachian coverlets as deserving recognition for their art historical value.

There are a few key historical sources I cite throughout this essay. Allen Eaton’s comprehensive history is invaluable writing on the Handicraft Revival. It is cited in every other source on the subject, and still provides an incredibly useful firsthand account of the movement. That being said, he has a tendency to stereotype his subjects as romanticized, hardworking mountain people who are eager to work with their hands and take immense pride in self-sustaining homesteads. While this is surely true of some people, Eaton assigns this attitude to the entire region, firmly establishing him as enthusiastic and earnest, yet misinformed outsider. Philis Alvic’s Weavers of the Southern Highlands draws on Eaton’s original work but gives a more in depth look at specific actors in the revival. Kathleen Curtis-Wilson’s book, Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women, published in 2001, provides a comprehensive collection of coverlets with the rare addition of information on the weavers who created them. It also includes pattern names and details, which are extremely useful to my analysis. Along with these essential sources, I reference relevant scholarship on textiles by Janis Jefferies and Rozsika Parker.

Coverlets and Materials

Coverlets are decorative woven bedcovers. They are typically woven in the overshot style, and all of the coverlets in this paper are overshot.32 Since the looms were not large enough to weave an entire coverlet at once, weavers made two separate panels and sewed them together after weaving. In most instances, the center seam is visible since matching the patterns perfectly required immense attention to detail and wasn’t considered necessary by most weavers. Ones without visible seams indicate incredibly skilled weavers and were likely meant to be sold, like the one by Josephine Mast here (fig. 4). If there is no seam at all, it is a factory-woven coverlet.33 Coverlet patterns are recorded in drafts, but the ability to read draft notation was dwindling by the time the Craft Revival began.34 Coverlet pattern names are also not fixed, one pattern can have different names in different counties. There are some patterns that were popular across the region, like the double bowknot.

Figure 4. Josephine Mast, untitled, 1920, coverlet weaving.

Though some weavers used pre-spun threads, most grew or locally sourced flax, cotton, and sheep to make their linen, cotton, and wool threads.35 Cotton and wool were more commonly used than linen, and weavers would card, pick, and spin their own cotton and wool. This was a laborious task. Most weavers also hand-dyed their threads, either with natural dyes from available sources or available synthetic dyes.36 Goodrich goes through multiple natural dye recipes, confirming that natural dye elements were still used well into the 20th century.37 The limited options from both natural and synthetic dyes required weavers to apply innovative color theory to create the desired effect. It makes the vivid and large range of colors achieved by home-dyers even more impressive.

Figure 5. Harris and Ewing, President’s Blue Mountain Room at the White House, 1913, photograph. https://wcudigitalcollection.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4008coll2/id/946/rec/40

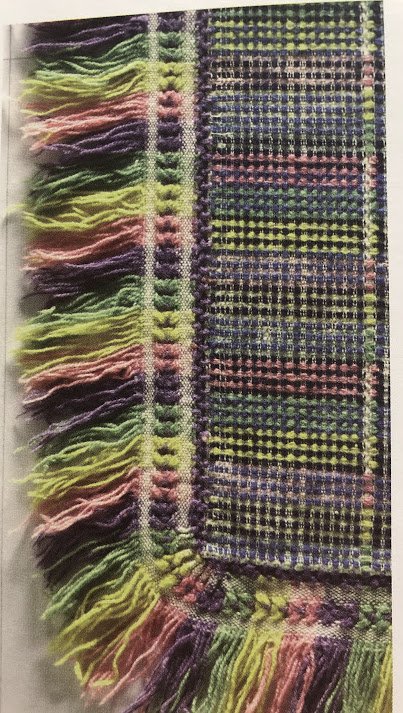

Josephine Mast (1861-1936) is by far the most notable weaver of the revival. From Valle Crucis, North Carolina, her family founded the Mast General Stores, which now operate across the southeast. Incredibly, Josephine Mast used her grandmother’s loom, built in 1820, and wove on it for over fifty years.38 She spun and dyed her own fiber for most of her life, though her late work did use commercially spun and dyed yarn.39 She was commissioned by first lady Ellen Wilson to provide weaving for the Blue Mountain Room in the White House in 1913 as seen here (fig. 5).40 This established her as one of the most commercially successful coverlet weavers of the time. This commission was also a significant factor in the growing northern market for southern-made goods. Since her coverlets were primarily intended to be sold, there is a level of detail not seen in the works of hobby weavers. For instance, she frequently finished coverlets with fringed borders as seen here (fig. 6). Due to her artistic and commercial success along with the quality of her extant work, I will reference Josephine Mast’s work throughout the essay along with a select few other coverlets.

Figure 6. Josephine Mast, Sun, Moon, and Stars Variation (detail), 1918, coverlet weaving.

Crafting Community and Feminism

The isolating geography of Southern Appalachia influenced every aspect of life. Outside of the few cities in the area, people lived with limited social opportunities. Weaving groups created a reason for female organization at a time when there were little to no reasons for women to congregate and socialize outside of church.41 In the most rural communities, church meetings only happened once or twice a year. 42 At Allanstand, Frances Goodrich “aimed most of all to give the women a place to go and get together and do business of their own that mattered in the real world.”43 The moral qualities missionaries like Goodrich assigned to weaving have strong overtones of Protestant work ethic ideology. They emphasized the quality of character such an honest practice created.44 While these weaving groups were morally idealized, they were practically and socially important. Women gathered to “discuss questions of supplies, weaving instructions, and shipping and marketing the finished work; but equally important is the social aspect where friends and relatives who had not come together over long periods, sometimes years, met more or less regularly.”45 In our interconnected age, it is hard to fathom going so long without any interaction with loved ones, especially ones living in the same county. The community and focus on education also gave many women the opportunity to pursue new interests. Eaton notes that through weaving he saw women take interest in “geography, history, sociology, science, and art.”46 Weaving groups facilitated knowledge-sharing and fostered community, both of which were crucial to the economic relevance of coverlets that I will discuss next.

Sexism, Racism, and Economics of Othering

The history of weaving in America is inextricable from the lived experience of women in the country since it was historically considered a woman’s craft.47 Rozsika Parker identifies “the historical hierarchical division of the arts into fine arts and craft as a major force in the marginalization of women’s work.”48 This phenomenon applies across American history. In Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s The Age of Homespun, she discusses the rhetoric of Horace Bushnell, a 19th century minister from Connecticut, and his public addresses. He coined the term “the age of homespun” in a speech on the virtue and importance of women’s spinning to the community.49 He proclaimed an “economy of homespun” would effectively create a utopian society of equality.50 This choice to economically center women’s work feels incredibly feminist for the 1800s. However, Bushnell quickly descends into sexism, calling spinning the best way to calm women’s “nervous impulse.”51 What presents like feminist economics quickly spirals into praising women for their meekness and silence while expecting them to perform free labor. According to Robertson and Vinebaum, “the devaluation of women’s hand-labor has undergirded many supposedly utopian projects.”52 This whole example is the perfect case study for the past weaving has to overcome. It illustrates the challenge for feminist readings of historical textile arts since for most of history, women did not weave entirely by choice. They were praised for weaving only because it was expected of them. After industrialization lessened that burden, women seeking education in the arts were relegated to this acceptably feminine practice. Even Anni Albers, arguably the most well-known textile artist of the 20th century, only started weaving because of gendered expectations.53 A feminist reading of textiles takes form when we see them as subverting sexism from within by using the means of female oppression to express female artistic freedom. By applying this idea to spinning and weaving, we can recognize both the sexist confines of weaving and the unexpected innovation and artistry that came from women refusing confinement. The title of Rozsika Parker’s The Subversive Stitch, wittily sums up this idea. Just because something is historically associated with oppression does not mean it cannot be used for liberation. Using tools of oppression to fight norms imbues them with even greater potency.

One of the primary subversive qualities of weaving in Southern Appalachia, outside of artistic freedom, was the economic impact of coverlet weavings. The personal financial importance of weaving for Southern Appalachian women is emphasized in all of the historical sources on the Craft Revival. The opportunity for women to make independent income was revolutionary. There was already very little economic opportunity in the rural Southern Highlands, so even small earnings were greatly valued.54 Alvic notes that when asked, most women stated they preferred working in the home, therefore weaving fit their needs.55 Being able to make money while staying at home was previously out of the question. At most centers, weaving was also flexible, since income was based on accepted commissions, and women could take as many or few as desired.56 Historically, textiles were used to occupy women and keep them in the home, so using them to gain income and freedom subverted centuries of oppression.57 Many chose to spend their earnings on their children’s education, some even sending their children to college with it.58 They also accessed new freedom to furnish their homes and purchase items for personal enjoyment, such as victrolas.59 We should not underestimate the immense difference in lifestyle items like these created for people previously living almost exclusively off of their land.60 While this supplemental income helped families to continue their long-lived mountain lifestyles in a rapidly modernizing world,61 it also gave women unprecedented financial power and influence in their family units.62

This brings us to the second question of feminism in this specific instance of weaving. While weaving helped women and their families continue living traditionally, was the traditional life better or equal to the opportunities for women in more industrialized parts of the country? There is no one answer here as lifestyle is on a case-by-case preference. Perhaps given the option to leave, some women would have, but travel was not easy then and meant leaving both home and family. Women were also gradually gaining independence economically and socially in the rural communities where they were from. While I do not disagree that these rural women may have led more fulfilling lives in a more urban context, the opportunities created by weaving greatly ameliorated their given situation. Moreover, their rural situation and continuation of tradition created a lot of their market appeal to consumers from outside of the region.63

Outsiders, people from areas other than Southern Appalachia, were integral in the Craft Revival. Without the protestant missionaries like Frances L. Goodrich and educators like William Frost, Appalachian handicrafts in their current form would not exist. They came to the region with new ideas for educational models and community engagement. They were also critical to identifying the economic potential of coverlet weavings. By the 1850s, the art of home spinning and weaving was largely lost in northern states.64 Becker’s Selling Tradition: Appalachia and the Construction of an American Folk, 1930- 1940, discusses the othering of “folk” traditions that underlies this market. The people of rural Appalachia were othered by “urban sophisticate” and added to the narrative of traditional America.65 Much of this othering was spurred by local color writers who traveled to the country in order to write about small pockets of people for urbanites’ enjoyment.66 These travel writers greatly romanticized the people and lifestyle of the region as an idyllic pastoral remnant of a forgotten time.67 The folk culture of Appalachia was made a foil to industrialized America and idealized as a kind of escape.68 Part of the desire for crafts from the region came from their association with “pure” American roots, aka an America of white European descent.69 Southern Appalachia became the locus of this racist ideal in the late 19th century after the abolition of slavery and the ensuing white panic.70 Overall, this othering was problematic both for its underlying racism and its overgeneralization of a diverse group of people. Appalachia was not exclusively white, but the image sold of it was. This false and racist idea was not considered by the weavers or organizations in any source I have read. However, this problematic consumer mindset is an important reminder that coverlets were a white tradition, and their positive effect did not seem to extend to people of color. While appreciating the progressive economic impact on individual Appalachian white women, we need to keep in mind the type of desires driving the demand and the groups excluded from the history of coverlets.

A Critical Language of Weaving and Art Historical Situating

Coverlet weaving’s reception has been largely typical of “craft” objects, included in cultural exhibitions and museums and therefore not allowed to exist aesthetically alone. We allow art to speak for itself through visual qualities, but we expect craft to be supported by culture and history. Coverlets are considered a craft in the art/craft divide which went largely unquestioned until the later 20th century.71 Before this, the division of art and craft dismissed traditionally feminine practices in textile as decorative and lacking the intellectual value of traditionally male art forms.72 Weaving was considered “too domestic and laborious to hold significant depth” according to scholarship on the Bauhaus attitude towards weaving.73 This is precisely what I am arguing against. The disregard for female labor and art is evident in the artistic devaluing of weaving. Considering this point, my argument is a type of feminist art recovery from this disregard. Coverlet weavings are not in complete obscurity; they are just artistically overlooked. There was one show of coverlets in 2001 curated by Kathleen Curtis Wilson, which I hope laid the ground for more museum appreciation of these works.74 However, this one show from twenty years ago does not constitute artistic recognition. It is an exceptional outlier. In order to advocate for this consideration, we have to re-frame our artistic vocabulary to fit textile art.

Figure 7. Doris Ullman, Mrs. Leah Adams Dougherty, 1933-34, photograph.

Weaving happens in its own language. It is not easy to explain in a linear manner due to the literally interwoven nature of textile art. We cannot use the same approach appropriate for painting or drawings. Weavers have to plan in terms of the loom and threads and capabilities of the grid. We need to find weaving’s own pictorial-structural terminology. Female Bauhaus weavers used the language of architectural functionalism in their argument for weaving as a specific and internally defined medium.76 Of these women, specifically Anni Albers and Otti Berger wrote extensively on the importance of tactile engagement, followed by structure and color. For Berger, durability was important throughout the critical process.77 I am working from their key concepts to consider coverlets.

To look holistically at texture, we have to look at the motions that created it. Since coverlets were handwoven, we can investigate them in terms of a singular artist. Handweaving requires the entire body. The feet move the treadle to alternately raise the weft and warp, the hands manipulate the weft through the warp, the body dances around the loom in order to weave. This rhythm is integral to how we understand construction. The structure of weaving itself indexes the movement of a woman in the act of creation. The rhythm of weaving creates the varied textures and nuances of the textile. Therefore experiencing the texture of coverlets is artistically intimate.

Figure 8. Josephine Mast, untitled, overshot coverlet.

In feeling the haptic qualities of the coverlet, it is natural to move to the identities of individual threads. Even in the tightest weave structure, each thread can be distinguished. Their texture is different alone versus within the larger composition. Albers discusses the affordances of different material and weave pattern combinations, which come into play here. In the simplest terms, this is how the weave pattern and fiber affect each other and gain agency in combination. For instance, wool in a standard weave versus a twill weave creates entirely different experiences.77 Threads may feel rough in isolation yet soft in the compositional context. In this example (fig. 8), we see how the condensed sections of purple weft threads appear softer than the warp-dominant white sections. Albers also emphasizes the importance of understanding raw elements and components when looking at texture. Since we primarily interact with finished products, the impact of handling ingredients and engaging with their transformation greatly informs our tactile sensibility.78 Therefore it is important to mentally deconstruct and reconstruct textiles to grasp their haptic qualities. We need to visualize the raw white warp of this work by Mast gradually coming together with the purple and orange wefts dancing through. Then we begin to grasp the foundations of texture.

Figure 9. Frances L. Goodrich, Sample Book, 1891, Southern Highland Craft Guild.

Senses do not happen in a vacuum. In experiencing the tactile qualities of a piece, we also take in the colors of the threads. In the previous figure, the contrasting textures are heightened by the opposing colors. Color is an integral part of how we perceive texture. Coverlet weavers employed color theory to achieve textural goals. As we see in Frances L. Goodrich’s sample book (fig. 9), the color choices of these small weavings greatly impact how we perceive their texture. The swatches on the left page use contrasting colors and values to create distinct layers. On the right page, three of the swatches (excepting the top left) opt for more cohesive colors that visually meld together, making the fabrics appear softer. In Goodrich’s writings, she outlines the laborious process of dyeing and mixing different colors.79 Some pigments were synthetic, others natural. The natural dyes were determined by locally available plants. These colors hold a unique connection to the land. In holding a pink section of a coverlet, you may be holding a long-gone madder that grew a hundred years ago.80 Even the synthetic dyes are tied to women’s hands through labor. The process of mixing dyes was not simple. The recipe for blue required: “½ a bushel pot full of warm water, 2 ounces of indigo in a little sack, 2 ounces of madder, or as much as you rub through of indigo. 1 teacup of wheat bran, or two handfuls, 1/2 pint of drip lye, or enough to make the bran feel slick or till water has a sweet taste.”81 Then one had to keep the dye pot warm for up to two weeks until the dye “comes” before the laborious task of dipping in the yarn to obtain color.82 Understanding the work behind coloring is an integral part of engaging with the visual and tactile qualities of a work, since it holds a chemical and artistic process entirely unique from the carding, spinning, and weaving of a coverlet.

The language of weaving must also include its functional aspects and how it interacts with its space. Fabric serves myriad useful purposes in our daily lives and coverlet weavings are not exceptions. They are decorative bed covers and made to keep users warm during cold nights. Typically made of cotton and wool, coverlets were woven in overshot style.83 This combination of material and structure gives them a thick weight for cold nights but enough soft pliability for comfort. In looking at the role they play in space, we see how coverlets interact with individual bodies, beds, the looms they were woven on, spaces of family pride after becoming old and precious, and spaces of display in the few cases where they are treated like art. Each space gives different functional and aesthetic qualities to a coverlet. Not only does spatial form change from a bed to a wall, but interaction with light changes, therefore color is affected in each scenario. The images we are seeing now only represent one identity of coverlets. Janis Jefferies summarizes this, stating that textile “never quite settles in the same space, can never be read in the same place, in the same way twice.”84 We give space the power to transform objects from mundane to art, and in doing so transform their visual qualities.

Figure 10. Josephine Mast, American Beauty, 1913, coverlet weaving.

After looking at these aspects, we see how they constitute an intentional visual experience, since coverlets were created with individual aesthetic goals. There is not a unified visual goal since each coverlet is unique, but the material affordances just discussed are evident in all of them. For instance, in Josephine Mast’s American Beauty (fig the physical relationship of the white warp and blue weft creates the illusion of a purple hue in the spaces where warp and weft are equally visible. In contrast with the concentrated squares of blue and lines of white, this purple gives the feeling of three distinct shades at work. This exemplifies the complex work coverlet weavers undertook using minimal resources. In American Beauty, she uses the difference of dark blue and light purple to emphasize the textural contrast in the star or flower pattern seen in this close shot (fig. 11). Focusing on this space between the primary circular motif brings the diagonal motion of this pattern to our attention. Initially overpowered by the gridded circles and squares, suddenly the subtle diagonals move our eyes in a completely new direction, aided by Goodrich’s choice to weave them in dark blue. This is the skill and artistry of coverlet weavers; they wove quiet complexities into the simplest patterns.

Figure 11. Josephine Mast, American Beauty (detail), 1913, coverlet weaving.

The more color used, the more difficult a work was to create. Sun, Moon, and Stars Variation by Mast (fig. 12) uses an exceptional eight colors, which was unheard of for most home weavers. The effect is visually exciting, the vibrant pink strands grab the eye and draw us into the rest of the piece.

Figure 12. Josephine Mast, Sun, Moon and Stars Variation, 1918, coverlet weaving.

These examples show how fibers and colors are actors that combine to create unique agency with the mobility of textile. Imbued with the artist’s intention, they form an engaging sensory landscape. As we see Mast’s movements indexed by the threads, we come to question why she chose this non-traditional color combination. The cloth invites almost all of the senses to interact with the colors, rhythms, textures, and modalities we’ve discussed. Looking at the fringe combined with the exuberant colors, we feel a playfulness from Mast. Despite the vast amount of work that went into this, the visual experience nods to her artistic ability which allowed Josephine Mast to have fun with her designs. Coverlets were a creative outlet, and this identifier is crucial in their artistic consideration because they hold the artist’s internality. Everything we see in a coverlet was a choice or a mistake, and both came from the same woman creator. In capturing a woman’s artistic agency, coverlets hold the culture which shaped her and the dreams she held in weaving it. They hold her artistic aspirations, accomplishments, and growth. This is the foundational component of how coverlets gain agency.

Their agency also changes over time with new cultural contexts. For instance, Josephine Mast’s American Beauty (fig. 11) takes on a new meaning in America’s partisan political landscape. Associating purple with Americanness invokes ideas of bipartisanship since it combines liberal blue and conservative red. On the other hand, the Whig Rose pattern (fig. 16) has less of a political association in modern America since the Whigs are not a relevant political party in the states. Therefore, the name brings ideas of old gardens and topiaries instead of battles in Congress. As seen in these examples, the names of patterns influence our reception of coverlets.

Figure 13. Mary Ellam Cuthbertson, Original Governor’s Garden, 1885, coverlet weaving.

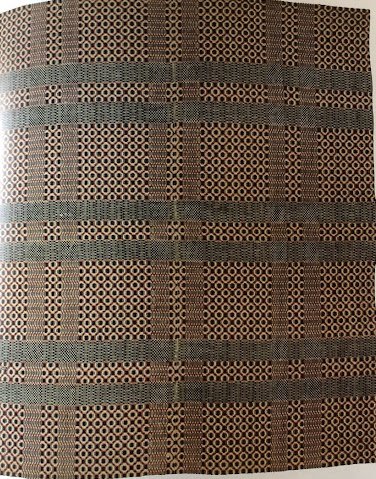

Coverlets also have stand-alone agency created by aesthetic choices. Looking at this variation on the popular Governor’s Garden pattern by Mary Elam Cuthbertson (fig. 13), Curtis-Wilson notes that this pattern is “easily altered by the weaver’s use of color and the width of the horizontal and vertical stripes.”85 Cuthbertson does just this by dyeing her warp threads a dark blue, which by showing through the weft, give the traditional diamond shapes the appearance of being circles.86 The circularity contrasts the rectilinear grid structure of the weaving and helps create the illusion of two layers, with the thick horizontal and vertical lines overlaying the pattern of circles. Constructing depth in a two-dimensional, non-figural medium requires skill and imagination as seen here. This is a testament to the creative innovations which took place in Appalachian coverlet weaving.

Figure 14. Sarah Murrell, Orange Peel Variation, 1850, coverlet weaving.

In this vein of tactility, textiles do not evoke the same feeling of restraint as with painting or sculpture which we fear ruining or breaking. While this may originally come from its lower artistic status, I see it as an incredibly useful attribute since we have to interact with cloth in order to fully grasp its artistic qualities. This is especially relevant with coverlets, since they were made to be used and seen in various modes. Textile interacts with different light sources and surfaces to create new textural identities. In this instance, we are looking at images of them through a screen, therefore experiencing coverlets in a limited manner. However, if we picked up Sarah Murrell’s Orange Peel Variation coverlet (fig. 14) and placed it over a sleeping person, the circles and diamonds would emphasize different diagonals and curves than they do laid flat. Textiles and their visuality are inextricably linked to their surroundings in this way.

Figure 15. Rachel McLin, Cat Tracks and Snail Trail with Border, 19th c., coverlet weaving.

Now that I have established a useful guide for artistically considering coverlets, I will apply coverlet weavings to a review of well-established textile art. The first artist who comes to mind is Anni Albers, who actually worked in Southern Appalachia from 1933-1950, but was not associated with local weaving.87 Albers is undeniably institutionally accepted and has a legacy beyond her lifetime as cemented by the major 2018 show at the Tate London. Now, I want to consider this description of her work:

There is an odd paradox between the perfectly linear grid of warp and weft that underlies textiles as a kind of lodestar for the designer, and the non-linear surfaces of Albers’s complex weavings. Her work captures her determination—through a developed understanding of the myriad complexities of interlacing vertical and horizontal—to undermine the grid, to make it virtually disappear by twisting and looping its threads.88

Figure 16. Mrs. Rhyne, Whig Rose, 1895-1920, coverlet weaving.

Though they did not come from prestigious European institutions, Appalachian weavers created aesthetically valuable works which fit this exact description, such as Cat Tracks and Snail Trail with Border (fig. 15). Characterized by the snaking lines across the pieces, this work moves the eye diagonally along the “snail trail;” and circularly on the “cat tracks.” This ability to create motion beyond the grid shows incredible attention to detail and meticulous thread counting alongside creative design. Being off count by one line shows in the finished pattern. McLin wove three directionalities and maintained precision in the difficult, curving snail trail throughout the work so that it not only moves from corner to corner, but also creates vertical and horizontal columns. Another example is the Whig Rose pattern (fig. 16), which is visually defined by the overlapping ovals framing small roses. Instead of outright rejecting the grid, this weaver maximizes its potential. By keeping the color palette simple and just using white weft and brown warp, the focus stays primarily on the geometry. The ovals overlap to create diamonds and almond shapes. Each oval contains four small roses surrounding one large one in the center. Inside each diamond is a small ornament, perhaps a rosebud. The idea of undermining the grid is not the only goal of textile art; embracing the rectilinear qualities of weaving also creates fascinating visual play. Grids hold deceptive freedom. We’re looking at grids every time we use computers or phones. We engage with complex images on grids every day, so it is unfounded to use them to aesthetically diminish weaving. In fact, it warrants greater praise for non-linear forms created by hand on grids.

Figure 17. Anni Albers, Monte Albán, 1936, silk, linen, and wool, Harvard Art Museum.

Finally, taking the titles into consideration, coverlet weavings like Whig Rose are representative geometric abstractions and repetitions. This is no different from Albers’ Monte Albán (fig. 17), a weaving which geometrically dissects and reconfigures a famous ziggurat in Mexico. Her title and treatment of her subject are theoretically and stylistically similar to coverlets of Governor’s Garden, Whig Rose, or Cat Tracks and Snail Trails. All take literal objects and artistically transform them into woven abstractions. They imbue them with the material affordances of textile. They apply color theory and textural complexity to accomplish visual innovation and interest. All are works created by women who found weaving as an unexpected creative outlet which blossomed into an artistic pursuit. Why then is Monte Albán in an art museum while these coverlets remain in artistic obscurity? This is the question I hope you too are asking after reading this brief advocation for the coverlet.

While coverlets now evoke ideas of a rural past, their artistic ethos is still present in the contemporary world. Whenever it seems that industrialization has finally gained supremacy, small revolutions like the Craft Revival arise. In our present day, the pandemic spurred a massive renewal of interest in creating clothing and goods at home. People took up handicrafts with a new fervor. Even though much of that enthusiasm has waned with the reopening of the world, the interest in handmade goods gained a strong foothold against the environmental negligence of fast fashion. Craft guilds and weaving groups have taken new forms in social media and e-commerce platforms where artists can sell directly to consumers. There is a clearly sustained demand for handmade goods and appreciation of their artistry.

On the artistic side, textile art has only grown in popularity with dedicated museum shows, market popularity, and increased innovation. In recent years, the Tate89, the Art Institute of Chicago90, and MoMA91 have dedicated shows to textiles. The art world is growing, and Appalachian coverlets with their feminist, economic, and artistic importance deserve recognition in this frontier of textile art.

Endnotes

Eaton, Allen H. Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands: With an Account of the Rural Handicraft Movement in the United States and Suggestions for the Wider Use of Handicrafts in Adult Education and in Recreation. (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1937), 29.

Shapiro, Henry D. Appalachia on Our Mind: The Southern Mountains and Mountaineers in the American Consciousness, 1870-1920. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1978), 115.

Eaton, Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands, 30.

Shapiro, Appalachia on Our Mind, 244-265.

Eaton, 30.

Eaton, 30.

Hassler, Warren H. “American Civil War,” in Encyclopedia Britannica. Last edited April 21, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/event/American-Civil-War

Hassler, Warren H. “American Civil War.”

Alvic, Philis. Weavers of the Southern Highlands. (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2015), 3.

Alvic, Philis. Weavers of the Southern Highlands, 3.

Alvic, 3.

Eaton, 59.

Eaton, 60.

Alvic, 77.

Alvic, 17-18.

Goodrich, Frances L. “Mountain Homespun” ed. Jan Davidson. (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2010), 6.

Eaton, 64.

Fariello, M. Anna. “Frances Goodrich” Craft Revival: Shaping Western North Carolina Past and Present (Western Carolina University, 2006). https://www.wcu.edu/library/DigitalCollections/CraftRevival/people/franceslgoodrich.html.

Eaton, 65.

Shapiro, 225.

Eaton, 66.

Eaton, 63.

Eaton, 60.

Alvic, 36.

Eaton, 64.

Eaton, 60.

Eaton, 69-91.

Alvic, 16-17.

Alvic, 17.

Alvic, 18.

Alvic, 21.

Goodrich, “Mountain Homespun,” 4.

Eaton, 116.

Eaton, 118.

Eaton, 97.

Goodrich, 13.

Goodrich, 13-16.

Wilson, Kathleen Curtis. Textile Art from Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women. (Lowell: American Textile History Museum. 2001-2002), 84.

Curtis Wilson, Textile Art from Southern Appalachia, 84.

Smithsonian, “Josie Mast: American Beauty Coverlet; overshot; c. 1913, North Carolina” National Museum of American History, 12-08-2021. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_620388.

Eaton, 35.

Eaton, 35.

Goodrich, 7.

Alvic, 8.

Eaton, 25.

Eaton, 36.

Parker, Rozsika. The Subversive Stitch (London: Bloomsbury, 2010), xiii.

Parker, Rozsika. The Subversive Stitch, xii.

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher, and Cairns Collection of American Women Writers. The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth. (New York: Knopf, 2001), 17.

Ulrich, The Age of Homespun, 17.

Ulrich, 17.

Robertson and Vinebaum, “Feminist Histories” in “Crafting Community” in Cloth and Culture 14, no. 1 (2016).

Albers, Anni, Gene Baro, and Brooklyn Museum. Anni Albers. (Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum, 1977), 10.

Alvic, 137.

Alvic, 137.

Alvic, 138.

Ulrich, 17.

Alvic, 142.

Alvic, 141.

Alvic, 136.

Alvic, 7.

Alvic, 9.

Becker, Jane S. Selling Tradition: Appalachia and the Construction of an American Folk, 1930- 1940. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 8.

Goodrich, 3.

Becker, Selling Tradition, 5.

Becker, 7.

Becker, 7.

Becker, 8.

Becker, 6.

Becker, 7.

Jefferies, 43.

Parker, Rozsika and Griselda Pollock, 2020. Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology. (London: Bloomsbury, 2020), 55.

Smith, T'ai Lin. Bauhaus Weaving Theory: From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 1.

“Textile Art from Southern Appalachia,” The McClung Museum, University of Tennessee, Knoxville. 2001

Smith, Bauhaus Weaving Theory, 44.

Smith, 97.

Albers, “Interrelation of Fiber and Construction” in On Weaving, 42.

Albers, “Tactile Sensibility” in On Weaving, 44.

Goodrich, 15.

Goodrich, 14-15.

Goodrich, 13.

Goodrich, 14.

Goodrich, 4.

Jefferies, Janis. “Textile Identity,” in Textile Sismographs, Symposium Fibres et Textiles- Texts from the Colloquium, Montreal: Conseil des arts textiles du Quebec, 1995, pp 20-28. In Contemporary Textiles: The Fabric of Fine Art. ed. Nadine Käthe Monem. (London: Black Dog Publishers, 2008), 23.

Curtis-Wilson, 20.

Curtis-Wilson, 20.

Coxon, Ann, Briony Fer and Maria Müller–Schareck. Anni Albers. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 15-16.

Coxon, Ann, Briony Fer and Maria Müller–Schareck, Anni Albers. 87.

Tate Museum, “Anni Albers” Exhibitions and Events, 2018. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/anni-albers.

Art Institute of Chicago, “Bisa Butler: Portraits” Exhibitions and Events, 2020. https://www.artic.edu/exhibitions/9324/bisa-butler-portraits.

Museum of Modern Art, “Taking a Thread for a Walk” What’s On, 2019. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/5101.

Bibliography

Art Institute of Chicago, “Bisa Butler: Portraits” Exhibitions and Events, 2020. https://www.artic.edu/exhibitions/9324/bisa-butler-portraits.

Albers, Anni. “Working with Material.” Black Mountain College Bulletin, 5, 1938.

Albers, Anni, Gene Baro, and Brooklyn Museum. Anni Albers. Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum, 1977.

Albers, Anni, Nicholas Fox Weber, Manuel Cirauqui, and T'ai Lin Smith. On Weaving. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Alvic, Philis. Weavers of the Southern Highlands. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2015.

Becker, Jane S. Selling Tradition: Appalachia and the Construction of an American Folk, 1930-1940. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Coxon, Ann, Briony Fer and Maria Müller–Schareck. Anni Albers. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018

Eaton, Allen H. Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands: With an Account of the Rural Handicraft Movement in the United States and Suggestions for the Wider Use of Handicrafts in Adult Education and in Recreation. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1937.

Fariello, M. Anna. “Frances Goodrich” Craft Revival: Shaping Western North Carolina Past and Present by Western Carolina University, 2006 https://www.wcu.edu/library/DigitalCollections/CraftRevival/people/franceslgoodrich.html.

Goodrich, Frances L. “Mountain Homespun” ed. Jan Davidson. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2010.

Jefferies, Janis. “Textile Identity”, in Textile Sismographs, Symposium Fibres et Textiles- Texts from the Colloquium, Montreal: Conseil des arts textiles du Quebec, 1995, pp 20-28. In Contemporary Textiles: The Fabric of Fine Art. Edited by Nadine Käthe Monem. London: Black Dog Publishers, 2008.

Museum of Modern Art, “Taking a Thread for a Walk” What’s On, 2019. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/5101.

Parker, Rozsika. The Subversive Stitch. London: Bloomsbury, 2010.

Parker, Rozsika and Griselda Pollock, 2020. Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology. London: Bloomsbury, 2020.

Pollock, Griselda. “Feminist Interventions in the Histories of Art: An Introduction,” in Vision and Difference,1-24. London: Routledge, 1988.

Robertson and Vinebaum, “Feminist Histories.” in “Crafting Community.” Cloth and Culture 14, no. 1 (2016): https://www.tandfonlinecom.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/doi/full/10.1080/14759756.2016.1084794?scroll=top&needAccess=true.

Siebenbrodt, Michael, and Schöbe Lutz. Bauhaus: 1919-1933, Weimar-Dessau-Berlin. Temporis. New York, USA: Parkstone Press International, 2009.

Shapiro, Henry D. Appalachia on Our Mind: The Southern Mountains and Mountaineers in the American Consciousness, 1870-1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1978.

Skelly, Julia. Radical Decadence: Excess in Contemporary Feminist Textiles and Craft. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

Smith, T'ai Lin. Bauhaus Weaving Theory: From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Smithsonian, “Josie Mast: American Beauty Coverlet; overshot; c. 1913, North Carolina” National Museum of American History, 12-08-2021. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_620388.

Tate Museum, “Anni Albers” Exhibitions and Events, 2018. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/anni-albers.

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher, and Cairns Collection of American Women Writers. The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth. New York: Knopf, 2001.

Washell, Kathryn F. “The Handweavers of Modern-Day Southern Appalachia: Ethnographic Case Study.” Eastern Tennessee State University. 2016

Wilson, Kathleen Curtis. Textile Art from Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women. Lowell: American Textile History Museum. 2001-2002

Wilson, Kathleen Curtis. “Textile Art from Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women” McClung Museum, 2001. https://mcclungmuseum.utk.edu/exhibitions/textile-art-from-southern-appalachia-the-quiet-work-of-women/.