Universality & Malleability: Icons of the Virgin at Saint Catherine’s Monastery

Written by Sam Lirette

Edited by Jacob Anthony

The Monastery of Saint Catherine at Mount Sinai in Egypt houses the largest collection of preserved Byzantine icons in the world (1). Specifically, I wish to examine three distinct types of icons held here (the Virgin Enthroned, the Hodegetria, and the Virgin of the Burning Bush), aiming to shed light on the evolution of Marian iconography by analyzing both pre- and post-Iconoclasm works, as well as site-specific icons. Additionally, the paper will lay out a brief history of the monastery, the iconographical origins of the Virgin, and the impact of the Iconoclasm. This will serve to contextualize the monastery’s icons, which, although relatively isolated, demonstrate the overall change in iconographic trends which occurred in the Byzantine Empire. However, this demonstration of general trends present within the Empire did not impede upon the creation of the monastery’s own local idioms and site-specific themes.

Although Saint Catherine houses a plethora of similar icons, I have chosen to examine the icons of the Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George (fig. 1), the Virgin Hodegetria Dexiokratousa (fig. 2), and that of Saint Catherine with the Virgin of the Burning Bush (fig. 3). These by no means cover the intricacies of the site’s icons, but for clarity and simplicity were chosen as larger representatives of these themes.

THE HISTORY OF THE MONASTERY AND ITS ICONS

Saint Catherine’s Monastery, built between 548 and 565 with support from Byzantine Emperor Justinian, is the oldest running Eastern Orthodox monastery in the world (2). It houses approximately three thousand icons, which are thought to have been preserved due to the monastery’s remote location, fortified nature and the area’s dry climate (3). Notably, the majority of these icons were created on the Byzantine mainland, such as in Constantinople, approximately 1500 km away (4). This proves crucial to my thesis, as these icons demonstrate the overall stylistic developments which occurred in the mainland; in other words, due to the monastery’s isolated nature, the works do not exhibit features expected to surface in these Eastern provinces controlled by Arab rule (5). In fact, many of these icons were donations from pilgrims, as the monastery—which is thought to be the site of the Burning Bush—is located on a route to the Holy Land (6). This aspect will prove important concerning both the creation of site-specific icons and the impact of pilgrimage. Interestingly, it is only through the association of the site with Saint Catherine of Alexandria by pilgrims in the 13th century that the site took on its current name. Documents show that it was not until the 16th century that it officially became known as Saint Catherine’s Monastery (7). In fact, the monastery was originally dedicated to the Virgin Mary, also known as the Theotokos in the Byzantine East, and it is therefore no surprise that Marian icons—specifically those of the Virgin and Child—far outnumber depictions of any other figure at the site.

ICONOGRAPHIC ORIGINS

As Marian iconography is both the focus behind my paper and arguably the monastery itself, it is crucial to analyze the origins of such iconography and the cult of the Virgin. In terms of icons which predate Iconoclasm, only about 36 survive (9). These are essential in understanding the development of themes. Thomas F. Mathews explores the roots of such motifs, noting the influence of Pagan and Egyptian goddesses. He notes the impact of ancient Egyptian icons, namely those of Isis, on the stylistic development of Marian iconography, ranging from their non-narrative frontal poses to the depiction of symbols of power (10). The collection at Mount Sinai, he argues, provides important evidence for the phenomenon of icons as a whole, and the early icons are in no way indicative of a new emerging genre (11). However, as illustrated by my diverse choice of icons of analysis, Mathews acknowledges the wide array of techniques employed by artists, which demonstrates a mastery of tempera, encaustic and gold leaf inlay (12). Most significantly, as Mary takes on the attributes of Isis, the site of the monastery proves important. It was in Egypt, after all, that the former received the title of Theotokos (God-bearer)—a title that originally belonged to the latter (13). Furthermore, Mathews argues that the Hodegetria may be understood as a conflation of Isis offering her breast to her child (14). Meanwhile, icons of the Virgin Enthroned are reminiscent of symbols associated with Isis: her hieroglyph was a throne, she protected the pharaoh’s throne, and her name originally meant “throne” as well—all of which point to a conflation between the two figures and Isis’ replacement by the Virgin Mary (15).

THE CULT OF THE VIRGIN AND ICONOCLASM

It is not surprising, considering the aforementioned evidence, that the Virgin eventually took on the role of holy protector. In his ground-breaking text on the history of images, Hans Belting explores how the Virgin took on this very role for the Byzantine Empire, providing divine aid in wars against Islamic powers, while simultaneously becoming a symbol of unity for the widely dispersed population of the empire (16). In this sense, she became an important uniting force after the death of Justinian. However, by the 8th century, Iconoclastic views grew in popularity and the Virgin’s status was deemed as oppressive (17). Icon production ceased and pre-existing ones were destroyed, though many at the monastery survived centuries of turmoil. It is in fact only after these periods of Iconoclasm (726-787, 814-842) that the Virgin took on the title of “Mother of God.” (18) Here, she takes on a more present and distinct role, often taking center stage in apse mosaics in newly standardized iconographic programs (19). As Belting makes evident, this period of Iconoclasm, although widely discussed, is filled with uncertainties and controversy which do not allow for simple conclusions concerning deeper conflicts between church and state (20). What is certain, however, is that this period of Iconoclasm resulted in a great loss of material in the Byzantine mainland; not a single work appears to have survived in Constantinople. However, the relative isolation and fortified nature of Saint Catherine’s Monastery allowed for the preservation of such pre-Iconoclastic icons.

THE VIRGIN ENTHRONED: THE PRE-ICONOCLASTIC

Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George

The 6th century encaustic icon of the Virgin (Theotokos) and Child between Saints Theodore and George (fig. 1) has been thoroughly studied and is referred to by several names. Due to its depicted theme, it will from here on out be referred to as the Virgin Enthroned. An analysis of this work will provide a key starting point for understanding the early icons at the monastery—and consequently throughout the Byzantine Empire—and serve to demonstrate later iconographic changes and preferences, which are far more standardized.

The icon depicts the Virgin Mary seated on a throne and holding the Christ Child. She is flanked by two saints, Theodore on her right and George on her left. All are dressed in their traditional regalia and are adorned with halos. Additionally, two archangels inhabit the background, gazing towards the hand of God which emerges from the top of the image. The icon is often studied for its simultaneous use of different stylistic techniques, such as Ernst Kitzinger who compares the dimensionality of the angels to the illusionistic frescoes found in Pompeii (21). Kurt Weitzmann, the leading art historian behind the discoveries at Mount Sinai, examines the impasto techniques used on the angels and relates it to their heavenly status, while the “sunburnt face of Theodore and the pallor of George” connote a more earthly presence and put the figures in contrast to Mary’s “supernatural appearance.”(22) Belting, however, reminds readers that this is open to controversy and instead focuses on form: the angels represent “open forms and movement in space,” the saints indicate a “closed surface with linear and neatly circumscribed forms,” the Virgin employs both of these, and the Christ Child leans more towards that of the angels (23). Although these formal analyses diverge in some areas, they both point to the fact that stylistic choices may be used to indicate distinctions between heavenly and earthly bodies. What is most interesting, perhaps, is the way the Virgin takes on an intermediary role; she is both of the heavens and of the earth, both spiritual and physical. Belting further states that these differences imply a hierarchy, which is further emphasized by the Virgin’s raised position on the throne (24). These aspects not only illuminate Mary’s intermediary role, but most significantly her intercessory role. This is where the importance of the gaze—of both figures and viewers—comes into play.

Firstly, the painting is rather large for an icon (68.5 × 49.7 cm) and is thicker at the top than at the bottom, perhaps indicating that it was meant to be hung from a considerable height and be viewed from below as an image of devotion (25). Indeed, icons, sometimes referred to as votive paintings, play an important role in prayer and devotion. Robin Cormack analyzes the gaze of such figures in order to understand the use of early Byzantine images. The frontal gazes of the saints, he argues, indicate their position as intercessory figures; viewers may direct their prayers to these earthly—although sanctified—individuals, which may then be directed through the more heavenly figures, and eventually to God (26). These roles, again, as emphasized by stylistic means, delineate sacredness and were most likely developed between the rule of Justinian and Iconoclasm (27). Furthermore, Mary’s gaze is not directed at the viewer but rather echoes that of the angels, indicating a certain holiness and intangibility; they gaze towards “an unseen vision.” (28) This balance between linear and organic forms, between differing gazes, reinforces the purpose of the icon as a devotional image, demonstrating how icons before Iconoclasm became an important part of everyday life and private devotion, offering access to God himself through the intercessory figures of the Virgin and saints (29).

Therefore, during the Pre-Iconoclastic period, as made evident by her enthroned position, the Virgin took on the role of protector for the entirety of the Empire, yet she simultaneously became an important figure concerning private devotion. The work consequently indicates that “there is no reason to think that the environment of the Sinai monastery was anything but representative of the Byzantine mentality.” (30)

THE HODEGETRIA & MARY AS MOTHER OF GOD: THE POST-ICONOCLASTIC

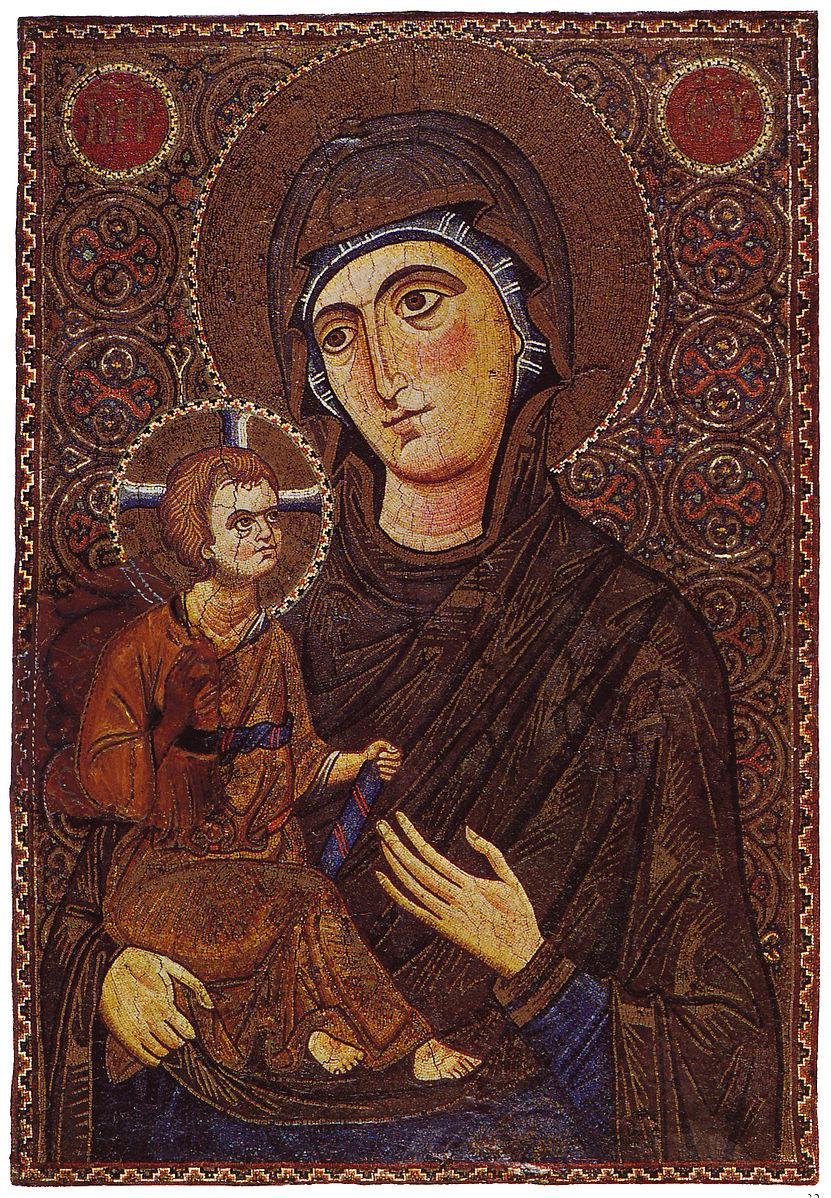

Icon with the Virgin Hodegetria Dexiokratousa

After the fall of Byzantine Iconoclasm, the role of the Virgin became progressively more important as artists and theologians developed new ways of understanding the figure and her maternal qualities, which further amplified her role as intercessor by increasing her accessibility (31). I shall examine the 13th century icon of the Virgin Hodegetria Dexiokratousa (fig. 2) in order to shed light on these changes in iconography and Mary’s new role as Mother of God.

Firstly, it is relevant to note that the icon is a mosaic set in wax on wood, which demonstrates exceptional technical skill indicative of metropolitan painters (32). This emphasizes, regardless of the monastery’s seclusion, a clear connection to the mainland. Here, the Virgin is depicted at half-length and holds the Christ Child. The latter raises his hand in blessing while the former points to him, hence the term Hodegetria, “She Who Leads the Way.” This iconographic depiction gained popularity after Iconoclasm, though it existed pre-Iconoclasm. In fact, the Hodegetria has a rich history of processions, especially in Constantinople, which harkens back to the legend of the original Hodegetria—a painting of the Virgin thought to be painted by Luke the apostle during her lifetime (33). However, in pre-Iconoclastic icons of the Virgin, the figure was simply referred to by her name or by the term Theotokos, “the One Who Bore God,” which neither relays any information about her specifically, nor does it imply any further relationship between her and the Christ Child (34). Here, on the other hand, we see the Greek inscription MHP ΘY, an abbreviation of ΜΗΤΗΡ ΘΕΟΥ, “Mother of God,” which clearly outlines this relationship (35). This maternal depiction of the Virgin positioned her as an “ordinary woman who understood humankind” and such intimate portrayals slowly took over the more formal, static illustrations of the Virgin as previously examined (36). Her intercessory role is present in the Virgin Enthroned, though symmetry and hierarchy supersede the motherly touch found in these later icons of the Hodegetria, rendering them, as Ioli Kalavrezou states, “unemotional and distant.” (37)

The increase in popularity of the Hodegetria emphasizes its importance in relation to the end of Iconoclasm; after all, the legend of St. Luke was created during Iconoclasm and played a key role in the approval of images (38). Furthermore, the icon’s rich processional history speaks to this. The Theotokos was often deliberately paired with scenes of the Crucifixion on pectoral crosses, which served to emphasize the words spoken by Christ before his death; he exclaims to Mary, “behold, this is your son” and to John, “behold, this is your mother” (John 19:26-27) (39). This choice performed by Iconophiles deliberately outlines the role of Mary as not only mother of Christ, but of all his disciples, and by extension as mother to all, shaping her as an incredibly approachable intercessor (40). In fact, her gesturing is interpreted as an intercessory prayer, which the Christ Child answers through his own gesture of blessing; the Hodegetria presents a dialogue of prayer which may be subsequently extended outside the picture plane and involve the worshipper (41).

Therefore, the Hodegetria illuminates the Virgin’s continued role as an intermediary figure, yet she becomes progressively more accessible through an emphasis on her motherly qualities. Unlike the Virgin Enthroned, the picture—and the relationship between viewer and figures—is far less hierarchical and formal. Furthermore, these qualities are indicative of broader thematic tendencies, as made evident by the historical significance of the Hodegetria in the capital. This ranges from the legends associated with the original icon to the processions which derived from it. The icons of the Monastery of Saint-Catherine, once again, demonstrate larger iconographic changes present within the entire Byzantine Empire. However, that is not to say that the monastery did not develop its own iconography.

VIRGIN OF THE BURNING BUSH: THE SITE-SPECIFIC

Saint Catherine with the Virgin of the Burning Bush

I wish to examine in brief the local idioms developed at Saint Catherine’s in order to emphasize its site-specific qualities. Although the monastery may be understood as a microcosm for the entirety of the Byzantine Empire—which may be understood in depth due to preservation—it would be improper to disregard the fact that, such as is the case for any sacred site, the Monastery at Mount Sinai developed its own exclusive imagery which speaks to its location on the supposed site of the Burning Bush.

The flux of iconographic themes between the secluded monastery and the mainland may be understood through the act of pilgrimage. As mentioned, many icons were brought to the site as offerings by pilgrims. These individuals were interested in the Monastery’s location—the site of the Burning Bush and Moses’ theophanic vision. It is therefore not a surprise that the icon of the Virgin of the Burning Bush developed in this location. The icon of Saint Catherine with the Virgin of the Burning Bush (fig. 3) depicts the Virgin, seemingly enveloped by the Burning Bush, holding the Christ Child and flanked by the titular saint. This scene presents a clear connection to the monastery’s site, and as made evident by the intertwining of flames with the figure of the Virgin, offers a definite association between the two and emphasizes the loca sancta of Sinai (42). These points consequently demonstrate the larger role she played specifically in relation to the site of the Monastery; her pairing—and literal fusing—with the site of the Burning Bush proved an unequivocal magnet for pilgrims.

CONCLUSION

The icons examined, from the Virgin Enthroned to the Hodegetria, demonstrate the ways in which the undisturbed collection of icons at the Monastery of Saint Catherine stands in for broader conceptualizations of iconography across the Byzantine Empire. Significantly, these works outline the impact of Iconoclasm on iconography, and the changes in thematic preferences which occurred after the end of this period. However, the Monastery at Mount Sinai also developed local idioms; the two are not mutually exclusive, as Kristine Marie Larison perfectly summarizes:

“The prominence of Marian imagery at Sinai should be understood in relation to her religious and cultural significance in Byzantium and the Orthodox East more broadly, as well as more specifically in relation to her theological and typological importance for the holy places of the pilgrimage site and monastery.” (43)

The Virgin, therefore, may be understood as the quintessential figure of both iconographic universality and malleability—allowing for the simultaneous creation of a shared identity across the Byzantine Empire and of unique particularities relevant to specific sacred sites.

Endnotes

1. Gerhard Wolf, “Icons and Sites. Cult Images of the Virgin in Mediaeval Rome,” in Images of the Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium, ed. Maria Vassilaki (Florence: Taylor & Francis Group, 2005), 25.

2. Kristine Marie Larison, “Mount Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine: Place and Space in Pilgrimage Art” (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 2016), 95.

3. Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 25.

4. Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art, 35.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Larison, “Mount Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine: Place and Space in Pilgrimage Art,” 182.

8. Ibid.

9. Thomas F. Mathews, “Early Icons of the Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine at Sinai,” in Holy Image, Hallowed Ground: Icons from Sinai, ed. Robert S. Nelson and Kristen M. Collins (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006), 39.

10. Mathews, “Early Icons of the Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine at Sinai,” 39.

11. Ibid, 41.

12. Ibid, 42.

13. Ibid, 47.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid, 49.

16. Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art, 35.

17. Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art, 35.

18. Ibid.

19. Larison, “Mount Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine: Place and Space in Pilgrimage Art,” 212.

20. Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art, 146.

21. Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art, 131.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Robin Cormack, “The Eyes of the Mother of God,” in Images of the Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium, ed. Maria Vassilaki (Florence: Taylor & Francis Group, 2005), 168.

26. Ibid, 170.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid, 168.

29. Ibid, 168-71

30. Ibid, 169.

31. Ioli Kalavrezou, “Images of the Mother: When the Virgin Mary Became Meter Theou,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 44 (1990): 165.

32. Nano Chatzidakis, “A Byzantine Icon of the Dexiokratousa Hodegetria from Crete at the Benaki Museum,” in Images of the Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium, ed. Maria Vassilaki (Florence: Taylor & Francis Group, 2005), 338.

33. Bissera Pentcheva, Icons and Power: The Mother of God in Byzantium (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006), 109.

34. Kalavrezou, “Images of the Mother: When the Virgin Mary Became Meter Theou,” 167.

35. Ibid, 171.

36. Kalavrezou, “Images of the Mother: When the Virgin Mary Became Meter Theou,” 165.

37. Ibid, 168.

38. Pentcheva, Icons and Power: The Mother of God in Byzantium, 124.

39. Kalavrezou, “Images of the Mother: When the Virgin Mary Became Meter Theou,” 168-9.

40. Ibid.

41. Pentcheva, Icons and Power: The Mother of God in Byzantium, 110.

42. Larison, “Mount Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine: Place and Space in Pilgrimage Art,” 215.

43. Larison, “Mount Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine: Place and Space in Pilgrimage Art,” 183.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Belting, Hans. Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image Before the Era of Art. Translated

by Edmund Jephcott. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Chatzidakis, Nano. “A Byzantine Icon of the Dexiokratousa Hodegetria from Crete at the Benaki

Museum.” In Images of the Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium,

edited by Maria Vassilaki, 337-58. Florence: Taylor & Francis Group, 2005.

Cormack, Robin. “The Eyes of the Mother of God.” In Images of the Mother of God:

Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium, edited by Maria Vassilaki, 167-74. Florence:

Taylor & Francis Group, 2005.

Kalavrezou, Ioli. “Images of the Mother: When the Virgin Mary Became Meter Theou.” Dumbarton

Oaks Papers 44 (1990): 165-72. doi:10.2307/1291625.

Larison, Kristine Marie. “Mount Sinai and the Monastery of St. Catherine: Place and Space in

Pilgrimage Art.” PhD diss., University of Chicago, 2016.

Mathews, Thomas F. “Early Icons of the Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine at Sinai.” In Holy

Image, Hallowed Ground: Icons from Sinai, edited by Robert S. Nelson and Kristen M.

Collins, 39-56. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006.

Pentcheva, Bissera. Icons and Power: The Mother of God in Byzantium. University Park:

Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006.

Wolf, Gerhard. “Icons and Sites. Cult Images of the Virgin in Mediaeval Rome.” In Images of the

Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium, edited by Maria Vassilaki,

23-50. Florence: Taylor & Francis Group, 2005.