The Aestheticization of Chinatown: A Sociopolitical Account of Montreal’s Paifangs

Written by Leighetta Kim

Edited by Thierry Jasmin and Maya Ibbitson

Chinatowns are one of the few ethnic districts that have survived into the twenty-first century. Having transitioned from ethnic ghettos to tourist destinations, the modern-day Chinatown rests on a long history of navigating discrimination. Despite the diversity of Chinatown occupants worldwide, including the different Chinese and Pan-Asian ethnic groups among other non-Asians, the same orientalizing images spur the distinction of Chinatowns from dominant societies. Chinatown authenticity is "made possible by the reification of historical goods or architecture" borrowed from Chinese tourist sites,1 particularly those which point to ancient Chinese iconography, rather than the environments most frequented by locals.2 Among these imported signifiers of Chinatowns are paifangs – decorative arches that distinguish districts and attract tourists by promising visitors an “authentic Chinese'' experience.3 Montreal’s Chinatown is home to the most paifangs in the country, with four in total;4 the North (René Lévesque Boulevard Est and St-Laurent Boulevard), South (St-Laurent Boulevard and Avenue Viger), West (Rue De La Gauchetière Ouest) and East facing arch (Rue de la Gauchetière Est and St-Laurent Boulevard). These landmarks were erected approximately a century after the first Chinese people settled in the area as part of an urban development strategy to distinguish the neighbourhood's Chinese-ness.5 They have since developed as the face of the iconic district – the first and last thing you see as you enter and leave. I will argue that Montreal’s paifangs exist as part of a greater aim to aestheticize Chinatowns, with this aim seamlessly translating into the Canadian notion of multiculturalism. Firstly, I will begin with a brief history of Chinatown’s beginning. Secondly, I will dive into the aesthetics of Montreal’s Chinatown, including its landmarks. Lastly, I will contextualise Chinatown’s paifangs within the discourse on Canadian multiculturalism.

The history of Montreal’s Chinatown is rooted in railroad-induced migration. Prior to major Asian migration waves on the Canadian West Coast, the first Chinese residents arrived in Montreal between 1825 and 1865 as servants.6 With the establishment of the Canadian Pacific Rail project, an endeavour rooted in the colonial desire to link Turtle Island’s British colonials to China, Chinese labourers were recruited from the United States and directly from China.7 As a result, 17,000 Chinese labourers were exposed to hazardous conditions as they worked on a 350km stretch of tracks while being paid half as much as their white counterparts.8 Sadly, 700 Chinese workers lost their lives due to these conditions.9 Extreme racism also impacted the lives of these workers as municipalities across the nation either enacted formal policies or informal restrictions to segregate Chinese access to urban space.10 As soon as the railroad was finished and Canada's dependency on Chinese labourers shifted, the Chinese Head tax was introduced in 1885 at $50, increasing to $100 in 1900 and $500 in 1903.11 In 1923, the Chinese Immigration Act was passed, completely excluding the entry of Chinese people to Canada until its repeal in 1947.12

Many Chinese workers returned to China after the railroad's completion. However, most found themselves stranded after the Canadian Pacific Railroad contractor, Andrew Onderdonk, broke his promise of sending them home.13 As a result, Chinese migrants traveled from BC to Montreal in hopes of finding new opportunities and escaping systemic discrimination.14 Upon arrival, they were united with the already growing population of Chinese settlers from the United States.15

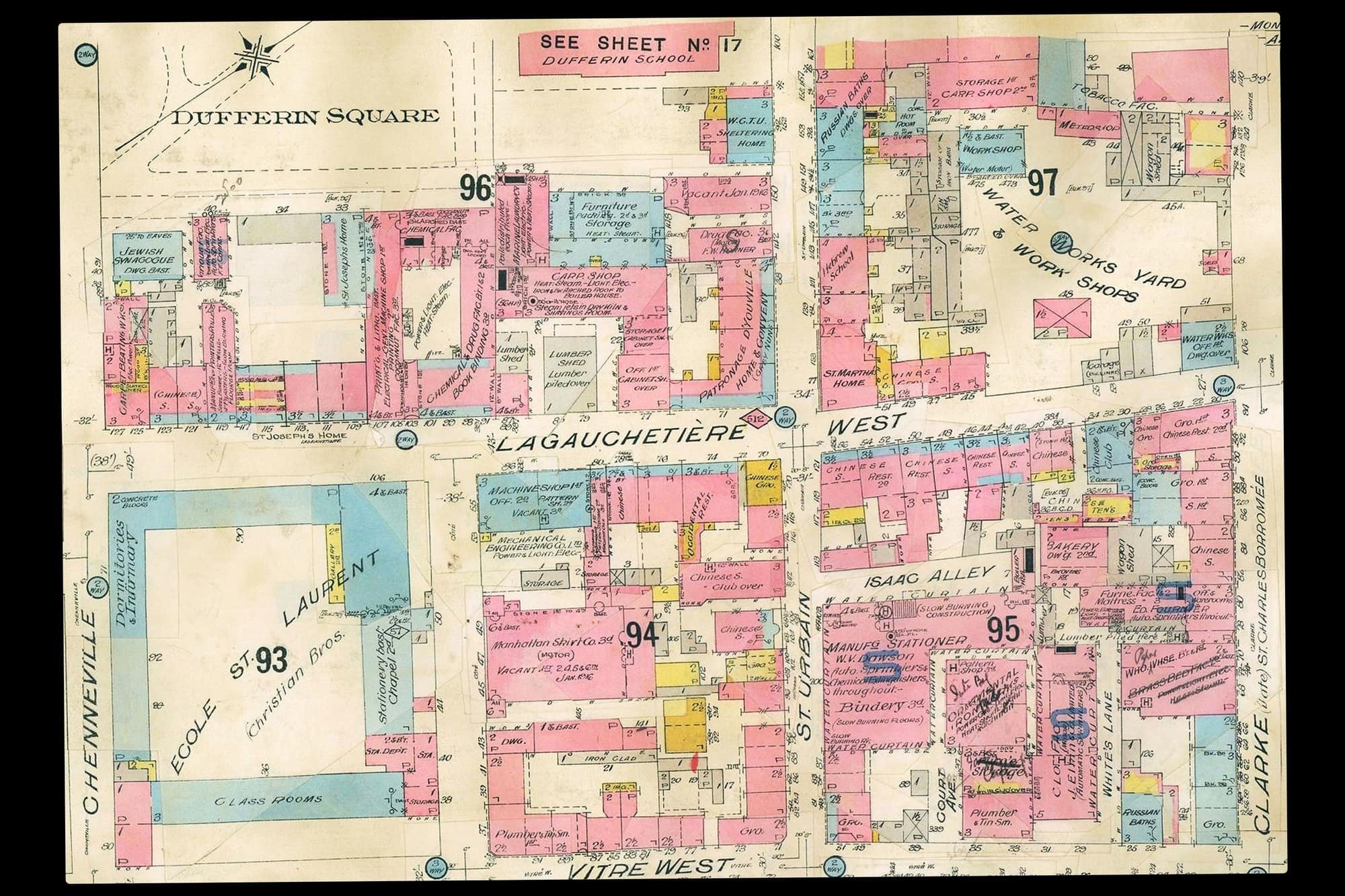

Thousands of Chinese laundries began to pop up around the city, and in the early 1900s, Chinese businesses began to concentrate in the Dufferin District. This neighbourhood, now recognised as Chinatown, was once known as a rundown residential area on the edge of the business district.16 Many property owners housed lodgers and rented out rooms, while the area also hosted a variety of warehouses and machine shops.17 Overall, Dufferin District hosted a large number of male residents working in the area or passing by in the lodging rooms. Consequently, there was a demand for services such as laundry and restaurants -- which Chinese immigrants filled.18 However, the development of Montreal’s Chinatown was not without its hardships. Chinese shop owners faced high levels of discrimination regarding licensing fees on top of their daily experiences with racism.19 In the insurance plan map below (fig. 1), we can see the makeup of the western side of Chinatown in 1909, which by this time already had a dominant Chinese presence in the area.

Figure 1. A 1909 insurance plan map of the neighbourhood.

By 1921, Chinatown was bound by Dorchester (now René Lévesque), Elgin (now Cark), de la Gauchetiere, and Chennevile streets. Chinatown continued to grow over the next thirty years, but considering the immigration restrictions, the pace significantly slowed down. By 1941 there was an extremely disproportionate gender ratio with approximately ten Chinese men to every Chinese woman. Many Chinese men had wives and children back in China, but with the immigration restrictions, most families remained separated. During this period, heightened anti-Asian racism persevered, influencing a number of segregating and discriminatory policies to be implemented across Turtle Island. While Quebec did not formally enact segregation laws, neighbouring provinces to the west prohibited Chinese men from employing, managing, or supervising white women.20 Rooted in the notions of yellow peril, Chinese men were seen as diseased deviant bachelors ready to leech on the sources of white men; steal jobs, land, and "their women." To quell these anxieties, Chinese men were conversely feminised and emasculated by mainstream society for their prevalence in running traditionally feminine services. While there were few Chinese women in Quebec during the beginning of the twentieth century, racist and sexist stereotypes still prevailed. Chinese women were stereotyped as hypersexual temptresses and often assumed to be diseased prostitutes.21 Accordingly, Chinese men and women were seen as undesirable citizens during a critical point in Canadian history, wherein demographic engineering was prioritised by both Prime Ministers and politicians alike.22 A combination between forced exclusion and a consequent desire for escape and solace within a community fostered the beginnings of Montreal’s Chinatown. In the following era, Chinatown was consistently going through changes. A mix of forced relocation, gentrification, and community development began to occur as the city of Montreal was looking to modernise. With the arrival of Expo 67, the city invested in a couple of infrastructure projects in Chinatown with the anticipation of thousands of tourists entering the neighbourhood.23 The City’s goal was for outsiders to be able to identify the neighbourhood as Chinese.24 This is where we see the beginning of Chinatown infrastructure as we know it today; the first to be built was Pagoda Park and large billboards with Chinese characters.25

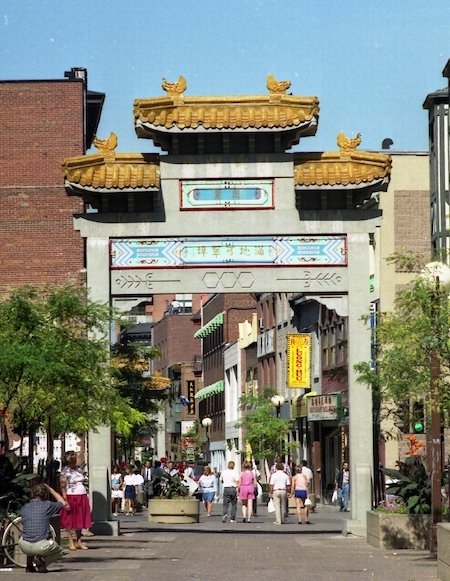

The first two paifangs were built in Montreal's Chinatown, by the municipal government, during the 80s and originally framed the heart of De La Gauchetiere Street (fig.3). When the larger main paifangs were erected on St-Laurent Boulevard in 1999 (fig.4), the other two were moved back towards St. Dominique and Jeanne Mance.26 The first paifangs were made of two grey concrete columns (unlike traditional variations which usually have four), light blue tile accents, ornamental engravings, and Chinese characters. The roof of the arch is composed of traditional rounded Chinese tiles of a golden hue, with four chickens sitting atop the highest points. The second paifangs are much larger in size, with double eaves and again, only two supporting columns. The roof is composed of the same rounded tiles but with the edges curving upwards in a classic sweeping style and dragons sitting atop each eave. The arch is painted a deep red, with decorative red, blue, and golden ceramic tiles. While these paifangs are not nearly as embellished with decorative elements as the traditional ones they aim to mimic, the authenticity they intend to signal does not necessarily derive from architectural accuracy, but rather a general aesthetic of ethnic difference.

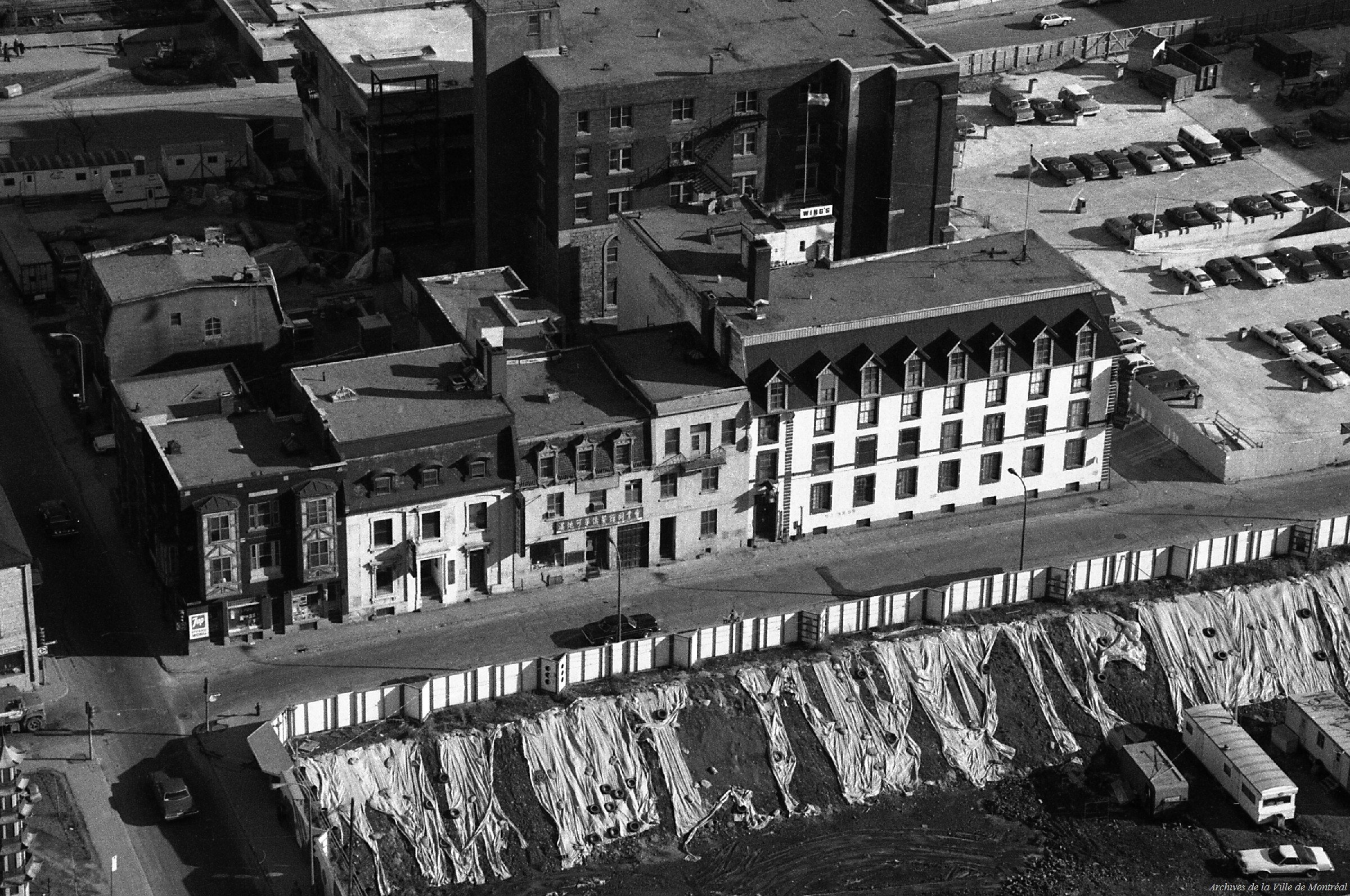

While landmarks such as the paifangs were beginning to pop up around the neighbourhood, Chinatown residents were being pushed out to make way for government buildings. The first round of demolition began with two large-scale provincial buildings on Dorchester (now Renelevesque), essentially blocking the area from expanding north.27 In 1981, the city planned to demolish a Chinese family association’s building and Pagoda Park to widen St. Urbain, which neighbourhood advocates petitioned against, resulting in only the demolition of Pagoda Park.28 The second round of government development occurred when the Guy Favreau Complex cleared six acres of land, including the demolition of nine buildings to widen Jeanne Mance.29 Two Chinese churches, a school, multiple Chinese grocery stores, arts and crafts stores, a Chinese food processing plant, and approximately twenty residential buildings were destroyed (fig. 2).30

Figure 2. This image captures only a portion of the land demolished for the Guy Favreau Complex.

Chinatown residents were furious and claimed that they were not properly consulted – a trend that has repeated itself over the course of history. As Margaret Kohn explains, cities “have adopted indirect measures in order to restrict residence and access.”31 The construction of the Guy Favreau Complex aimed to do just that – restrict residence and access – through the high prices of rent, ultimately pushing Chinese tenants out of their historic dwelling.

The completion of the Guy Favreau Complex in 1984 started a trend for public and private developers. The district attracted the eyes of developers for its prime location, situated on the edge of downtown, Old Montreal and Place des Arts. To make matters worse, in 1985, a municipal zoning bylaw was passed restricting commercial development on Rue De La Gauchetiere from expanding east of St. Laurent Boulevard.32 The chain effects of such development have led to increased property values, taxes, and rents – which has ultimately laid the foundation for many more waves of gentrification to come.33 Since this initial spike in property development during the 1980s, as Chinese properties were being chipped away, more and more Chinese families have been leaving the neighbourhood.

Occurring simultaneously with this first wave of gentrification, the construction of the paifangs speak to the beginning of the aestheticization of Montreal's Chinatown. While the neighbourhood became increasingly less-Chinese in terms of its demographics, landmarks like paifangs, which played a trivial role in the daily lives of residences, were being built. Yon Hsu explains that Chinatowns were "made to facilitate an economic strategy for post-industrial, service-oriented urban developments," which in turn created "an image of political multicultural diversity and urban cosmopolitanism constituted by pockets of 'authentic' differences."34 The paifangs of Montreal's Chinatown are the first signs of aesthetic difference that frame the neighbourhood's borders.

Figure 3. One of the first two paifangs in Montreal’s Chinatown, as seen in 1991 on De La Gauchiere street before it was moved in 1999.

Figure 4. The North and South paifangs after their restoration in 2016.

As the most iconic landmarks distinguishing Montreal’s Chinatown, their existence nestles perfectly within Canada’s notion of multiculturalism. Multiculturalism became official policy in 1971 with the aim to “‘help minority groups preserve and share their language and culture, and to remove the cultural barriers they face.’"35 This policy has been highly critiqued for the ways in which it centers white-anglophone culture as the universal standard. Multiculturalism fosters this dynamic by attributing a greater level of power to whiteness through its naturalisation as a synonym to “Canadian”. Meanwhile, under multiculturalism, minority cultures exist – only in relation to said whiteness – as signs of difference from the “Canadian” standard. Multiculturalism positions ethnic minorities as stagnant cultures only composed of easily digestible factions, such as cuisine and folklore.36 Ethnic groups are then mobilised as the nation's side characters, helping to build the Canadian image through their institutionalised participation.37 This in turn grants the state the ability to assert control over minority groups while utilising them for their own cultural image.38 As Chinatowns are constructed through the exaggeration of cultural goods, Montreal’s paifangs exist as this first taste of the tokenized minority – signalling to outsiders that Canada welcomes and values minority cultures while simultaneously employing orientalism.

Multiculturalism, gentrification in Chinatown, and the erection of the first two paifangs were all simultaneously occurring during the 1980s. As mentioned earlier, Chinatown itself grew out of the extreme anti-Asian racism in Canada and the need for the Chinese community to find solace within each other. Yet now, despite the ethnic minority being celebrated as part of the benevolent Canadian image, they are being denied agency over the very lands they were cornered into. Under multiculturalism, ethnic groups are reduced to a position where they can only request changes rather than authorise them.39 The general lack of political and economic legitimacy granted to Chinatown over the years, as seen through earlier examples of gentrification, speaks to the ways in which it has come to symbolise a marker of diversity to the state. As mentioned earlier, landmarks like the paifangs grew out of a desire to sell the “Chinese-ness” of Chinatown to outsiders, namely tourists. They were not constructed during the height of the neighbourhood, prior to gentrification, but rather in a moment wherein Chinese families were being pushed out to make way for upper-middle-class interests. Ultimately, the paifangs functioned to signal a certain level of “authenticity” that outsiders found desirable.

Underneath this façade is a community that has been consistently fighting for its survival since its inception. Attacks against Chinatown did not stop once Canada decided to brand itself with benevolence. With the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic at the beginning of 2020, Chinese people (and other Asians) faced racist blame for the virus, resulting in the north-facing paifang in Montreal being vandalized.40 Many other landmarks in the neighbourhood were damaged, Asian-owned stores faced a spike in break-ins and individuals were victims of violent hate crimes.41 In 2021, there has been a new wave of gentrification threatening the survival of Montreal’s Chinatown yet again.42 Walter Tom, a member of Montreal's Chinatown Working Group and an advocate against the neighbourhood’s continued gentrification, echoed statements expressed by the early generations of Chinatown occupants. He explains that Chinatown “is where [Chinese people] can seek relief from xenophobia and other racism.… This is where we grew up. This is really chez nous.”43

It is clear that Montreal’s Chinatown continues to occupy a space of solace for its community, despite the years of threats to its survival. Chinese Canadians have repeatedly been told that they do not belong and are not valued within Canadian society. Chinatowns exist because of this history; they "have been paradoxical because both the nonplace of exotic universalism and the lived space of everyday experiences have been mutually articulated.”44 The paifangs play with this tension through their transgressive nature, marking the difference between minority and dominant culture as well as between aestheticization and lived experience.

Endnotes

Ien Ang, “Chinatowns and the Rise of China,” Modern Asian Studies 54, no. 4 (July 2020): 1378.

Ang, “Chinatowns and the Rise of China,” 1378.

Paul Yee, Chinatown: An Illustrated History of the Chinese Communities of Victoria, Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal and Halifax (Toronto: J. Lorimer, 2005), 99.

Ang, 1378.

Yee, Chinatown: An Illustrated History of the Chinese Communities of Victoria, Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal and Halifax, 100; Chan Kwok, “Ethnic Urban Space, Urban Displacement and Forced Relocation: The Case of Chinatown in Montreal,” Canadian Ethnic Studies 18, vol. 02: 65.

Deborah Cowen, “Following the infrastructures of empire: notes on cities, settler colonialism, and method,” Urban Geography 41, no. 04 (2020): 477.

Cowen, “Following the infrastructures of empire: notes on cities, settler colonialism, and method,” 477.

Cowen, 477.

Cowen, 477.

Kwok, “Ethnic Urban Space, Urban Displacement and Forced Relocation: The Case of Chinatown in Montreal,” 69; Cowen, 477.

Kwok, 69.

Isabel Sarah Wallace, “Racial Segregation of Asian Canadians,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, October 18, 2018,

Wallace, “Racial Segregation of Asian Canadians,” 2018.

Cowen, 477.

David Chuenyan Lai and Timothy Chiu Man Chan, “Montreal Chinatown 1893-2014,” Simon Fraser University, 2015.

David Chuenyan Lai and Timothy Chiu Man Chan, “Montreal Chinatown 1893-2014”.

David Chuenyan Lai and Timothy Chiu Man Chan, “Montreal Chinatown 1893-2014”.

Wallace, “Racial Segregation of Asian Canadians,” 2018.

Wallace, 2018.

Maria Hwang and Rhacel Salzar Parrenas. “The Gendered Racialization of Asian Women as Villainous Temptress,” Gender and Society 35, no.4 (August 2021): 571.

Jean Bruce, The Last Best West. Montreal: Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, 1976.

Diane Sabourin and Maude-Emmanuelle Lambert, “Montreal’s Chinatown,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, March 24, 2013.

Sabourin and Lambert, “Montreal’s Chinatown”.

Sabourin and Lambert, “Montreal’s Chinatown”.

Sabourin and Lambert, “Montreal’s Chinatown”

Jesse Feith, “Chinatown renovations frustrate local businesses,” Montreal Gazette, July 7th, 2016.

Kwok, 70.

Domenic Vitiello and Zoe Blickenderfer, “The planned destruction of Chinatowns in the United States and Canada since c.1900,” Planning Perspectives 35, no.01 (2020): 98.

Kwok, 70.

Kwok, 70.

Margaret Kohn, “Dispossession and the right to the city” Place, Space and Mediated Communication, edited by Carolyn Marvin and Hong Sun-ha (London: Routledge, 2017), 70.

Kwok, 71.

Kwok, 71.

Yon Hsu, “Feeling at Home in Chinatown—Voices and Narratives of Chinese Monolingual Seniors in Montreal,” International Migration & Integration 15 (2014): 332.

Eva Mackey, “Managing the house of difference: official multiculturalism” House of Difference: Cultural Politics and National Identity in Canada, (London: Routledge, 1998), 77.

Mackey, “Managing the house of difference: official multiculturalism,” 79.

Mackey, 79.

Mackey, 79.

Mackey, 79.

Anne Leclair, “Montreal’s Chinatown faces second wave of vandalism, break-ins,” Global News, October 26, 2020.

Leclair, “Montreal’s Chinatown faces second wave of vandalism, break-ins,” 2020.

Melinda Dalton and Holly Cabera, “Saving Chinatown,” CBC, October 26, 2021.

Melinda Dalton and Holly Cabera, “Saving Chinatown,” 2021.

Hsu, “Feeling at Home in Chinatown—Voices and Narratives of Chinese Monolingual Seniors in Montreal,” 333.

Bibliography

Ien Ang. “Chinatowns and the Rise of China,” Modern Asian Studies 54, no. 4 (July 2020): 1367-1393.

Bruce, Jean. 1976. The Last Best West. Montreal: Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited.

Cowen, Deborah. “Following the infrastructures of empire: notes on cities, settler colonialism, and method.” Urban Geography 41, no. 04 (2020): 469-486. DOI: 10.1080/02723638.2019.1677990

Dalton, Melinda and Holly Cabera. 2021. “Saving Chinatown.” CBC, October 26, 2021. https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/saving-chinatown/

Feith, Jesse. 2016. “Chinatown renovations frustrate local businesses” Montreal Gazette, July 7th, 2016. https://montrealgazette.com/news/local-news/chinatown-renovations-frustrate-local-businesses

Hsu, Yon. “Feeling at Home in Chinatown—Voices and Narratives of Chinese Monolingual Seniors in Montreal.” International Migration & Integration 15 (2014): 331-347. DOI: 10.1007/s12134-013-0297-1

Hwang, Maria and Rhacel Salzar Parrenas. “The Gendered Racialization of Asian Women as Villainous Temptress.” Gender and Society 35, no.4 (August 2021): 567-576. DOI: 10.1177/08912432211029395.

Kohn, Margaret. 2017. “Dispossession and the right to the city.” Place, Space and Mediated Communication, edited by Carolyn Marvin and Hong Sun-ha, 66-79. London: Routledge.

Kwok, Chan. “Ethnic Urban Space, Urban Displacement and Forced Relocation: The Case of Chinatown in Montreal.” Canadian Ethnic Studies 18, vol. 02: 65-85. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/montreals-chinatown

Lai, David Chuenyan, and Timothy Chiu Man Chan. “Montreal Chinatown 1893-2014.” Simon Fraser University. http://www.sfu.ca/chinese-canadian history/montreal_chinatown_en.html

Leclair, Anne. 2020. “Montreal’s Chinatown faces second wave of vandalism, break-ins.” Global News, October 26, 2020. https://globalnews.ca/news/7423592/montreals-chinatown-second-wave-vandalism-break-ins/

Li, Chuo. “Interrogating Ethnic Identity: Space and Community Building in Chicago's Chinatown.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 27, no. 1 (Fall 2015): 55-68.

Mackey, Eva. 1999.“Managing the house of difference: official multiculturalism.” In House of Difference: Cultural Politics and National Identity in Canada. London: Routledge.

Sabourin, Diane, and Maude-Emmanuelle Lambert. “Montreal’s Chinatown.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, March 24, 2013. http://bitly.ws/pioM.

Vitiello, Domenic, and Zoe Blickenderfer. “The planned destruction of Chinatowns in the United States and Canada since c.1900.” Planning Perspectives 35, no.01 (2020): 143-168. DOI: 10.1080/02665433.2018.1515653

Wallace, Isabel Sarah. 2018. “Racial Segregation of Asian Canadians” The Canadian Encyclopedia, October 18, 2018. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/segregation-of-asian-canadians

Yee, Paul. 2005. Chinatown: An Illustrated History of the Chinese Communities of Victoria, Vancouver, Calgary, Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal and Halifax. Toronto: J. Lorimer.

Yon Hsu, “Feeling at Home in Chinatown—Voices and Narratives of Chinese Monolingual Seniors in Montreal,” International Migration & Integration 15 (2014): 331.

Images

Dalton, Melinda and Holly Cabera. 2021. “Saving Chinatown.” CBC, October 26, 2021. https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/saving-chinatown/

This image captures only a portion of the land demolished for the Guy Favreau Complex. “VM94-B259-028,” Montreal Archives. https://archivesdemontreal.ica-atom.org/vm94-b259-028

One of the first two paifangs in Montreal’s Chinatown, as seen in 1991 on De La Gauchiere street before it was moved in 1999. “VM94-A1025-006.” Montreal Archives. https://archivesdemontreal.ica-atom.org/vm94-a1025-006

The North and South Paifangs after their restoration in 2016 “CHINATOWN ARCHES AND PAGODA.” St-Denis Thompson. https://stdenisthompson.com/en/our-work/chinatown-arches-and-pagoda