Le Grand Escalier du Nouvel Opéra: A Feminist Approach

Written by Robert Pelletier

Edited by Sam Lirette and Jacob Anthony

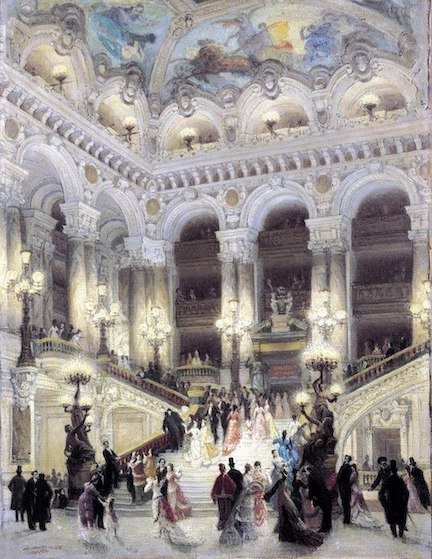

Massive and hulking yet sumptuous and elegant, the Nouvel Opéra de Paris stands at the end of a long boulevard, not calling attention to itself, but demanding it. Like the nearby Arc de Triomphe, Louvre, and Hôtel des Invalides, Charles Garnier’s Nouvel Opéra acts as an urban node around which the city is organised.1 This is no accident; Baron Haussmann’s Reconstruction of Paris from 1853 to 1870 dramatically altered the city’s urban fabric, transforming it into an essay on hierarchy, clarity, and the supposed rationality that guided design following the populist revolutions of the nineteenth century amid the waning Enlightenment era. Designed by Charles Garnier and finished in 1875, the Opéra is a massive, sumptuous building that terminates the Avenue de l’Opéra, bookended on the other side by the Louvre. Functioning as an urban centerpiece, the square in front of the Opéra sees the intersection of seven boulevards aboveground. Underground, three separate metro lines converge at the Opera, demonstrating the site’s continued significance into the twenty-first century. The high level of importance ascribed to the building is intentional; as a center of Parisian life, the Opéra was a symbol of modernity in the days of its conception, functioning as a space for spectacle and spectatorship.2 Its architecture combines the supposed rationality of the Beaux-Arts tradition with the sumptuous touch of the Baroque and Rococo, like a Versailles in the center of Paris, framing itself as a palace of the people. A palace it certainly is: its massive auditorium, multiple levels of entry halls, and sprawling backstage with dizzyingly high spaces for technical theatre equipment, the Nouvel Opéra is a mass that both breaks and accentuates the architectural rhythm of the rest of Paris. The Opéra’s main staircase, the Grand Escalier, is a particularly notable space located centrally within the building, drenched in ornament and positioned so that every visitor would pass through it (fig. 1). In its ornamentation and architecture, the monumental staircase crystallizes not just the essence of the Nouvel Opéra, but of Paris itself. The Grand Escalier sites the contradictions of Second Empire society that existed in post-Haussmann Paris; acting as a microcosm of newly modernised Paris, the space privileges the flâneur, veils the Parisienne, and erases the existence of those who do not perform social respectability.

Figure 1. Jean Béraud, L'escalier de l'opéra Garnier, 1877. Oil on canvas. Musée Carnavalet, Paris.

Baron Haussmann’s reconstruction of Paris was commissioned by Napoleon III in an attempt to surpass London and solidify Paris as the world capital of modernity, industry, and luxury.3 From 1853 to 1870, Paris was enveloped in dust from the demolition of “slum” housing and the construction of new uniform architectural façades, limited in height to six storeys and centered around urban nodes like the Nouvel Opéra. The extensive demolition throughout the city displaced many Parisians, affecting the lower and working classes most intensely;4 it also resulted in a perceived increase of sex workers in Paris who now, unhoused, were forced onto the streets.5 Wide, broad boulevards like the Champs-Élysées were used to promote light and ventilation through the previously narrow city streets as well as to expedite the quelling of rebellion.6 The 1848 Revolution depended heavily on the ability to barricade the narrow Parisian alleys, and Haussmann’s decision to clear these medieval historic alleys in favour of wide boulevards was, as many scholars have already suggested, highly politically motivated.7 The introduction of wide boulevards privileged the act of looking reserved for the flâneur, a character described by Charles Baudelaire as “the passionate spectator,” necessarily male, who can stroll around the city unchaperoned and unnoticed, watching and visually possessing all that he sees without necessarily being a part of it.8

The style officially adopted by the city of Paris and Haussmann was what is now referred to as the Beaux-Arts style, named after the École des Beaux-Arts. The École is the foundation of academicism in French architecture, sometimes referred to as the first dedicated school of architecture.9 They centered their pedagogy on historical precedent, particularly Greco-Roman antiquity, and the supposed rationality of the neoclassical style.10 Masculinity, hierarchy, classical ornament, and visual clarity were central in their theory, evident throughout its bureaucratic organization, pedagogy, and student life.11 It was the Union des Femmes Peintres et Sculpteurs, an all-female arts group founded in 1881, who advocated for the admittance of women artists into the École, which they accomplished in 1903.12 Nevertheless, the École embodies a style and pedagogy of architecture that prioritizes the flâneur’s presence in the city, and the new uniform Beaux-Arts façades of Paris served as the backdrop against which women, sex workers, and other marginalized groups were written out of public life. Charles Garnier, a student of the École, transcended the rational neoclassical style and moved toward the Baroque in his sumptuous, decorative design for the Nouvel Opéra. This was partly an attempt at democratizing the space, adopting the ornament and decoration typically associated with the aristocratic architecture of the Baroque and Rococo movements to a public establishment, framing itself as a palace of the people. While theoretically progressive, in practice the Opéra served not only as a backdrop for, but actively enforced, the doctrine of separate spheres and centering of the male experience.

Concerned entirely with the public sphere, the process of Haussmannization was effectively a process of masculinization. The doctrine of separate spheres gendered public space masculine, and private space feminine, resulting in women’s inability to experience the city alone and unchaperoned at the risk of being perceived as a sex worker or a woman of ill social standing.13 Of course, this is a generalisation; women did frequent public space alone, but in so doing, were forced to accept the risks involved. Modernized and freshly renovated, late nineteenth century Paris was saturated with rigid social expectations that dictated the performance of social respectability to uphold masculine myths. In her writing, Marni Kessler outlines three types of urban maskings introduced with Haussmannization: the uniform building façades, the layer of dust from demolition and construction, and the popular women’s fashion accessory of the time, the veil.14 The uniform Beaux-Arts façades imposed by Haussmann set the stage for interactions of various social identities informed by gender, class, sexuality and profession (contributing to the formation of caricatured archetypes like the flâneur, the sex worker, the Amazone, the Parisienne, etc.) in a spectacle of modernity.

III: Power in LookingThe act of looking, especially on behalf of women, was a source of anxiety among men in Second Empire Paris; like the public sphere, looking was an act reserved for men. During Haussmann’s reconstruction, the veil, a face-covering fashion accessory, rose in popularity as a bourgeois accessory in response to the dust and soot that polluted the city air as buildings were demolished and constructed.15 Its popularity among upper-middle class Parisiennes was enabled by the new process of mass-production and the rise of the department store.16 However, the veil’s ability to screen out dust was limited; the real intent of the veil was the diminishment of the female gaze. Add this to women’s inability to experience the city unchaperoned and the role of the veil in subjugating women becomes clearer.17

In her reading of Mary Cassatt’s painting In the Loge (1878), Griselda Pollock argues that “social spaces are policed by men’s watching women,” which becomes all the more evident when Garnier reveals his intentions are in line with that.18 Garnier was well aware of the charged social attitudes around the act of looking in nineteenth-century Paris and capitalized on these attitudes to men’s advantage. In his writings on the Opéra from 1878-81, he wrote:

“Oui mesdames; oui, j’ai pensé à vous en installant à droite et à gauche ces grandes glaces sans cadre qui remplissent toute la surface des fausses baies. Il est bon qu’avant de monter cette suite de marches sur lesquelles vous serez vues de tous vos admirateurs, vous puissiez donner un peu plus d'élégance à votre costume, abaisser votre capuchon et bien relever les plis de vos jupes… C’est bien le moins que vous, qui êtes à la fois le modèle et le tableau motivant, vous étudiez aussi votre costume et votre maintien.”19

Garnier directly acknowledges his design intentions in prioritizing the male gaze and objectifying the female body while limiting the scope of the female gaze to her own body and garments. By provoking female self-consciousness, he intentionally provokes female self-critique. The architecture of the Grand Escalier, as Garnier directly notes, actively enforces this through strategic placement of mirrors.

Considering the contemporary social context before delving into a feminist analysis of the Grand Escalier is critical because the building is a piece of social architecture, functioning not to host events as much as providing a space for social interaction to take place—for men to see and for women to be seen. Central in Second Empire society was the doctrine of separate spheres, a binary system where public space is gendered masculine and private and domestic spaces are gendered feminine. The Nouvel Opéra constitutes, I argue, a space that presents itself as public but in practice straddles the public and private. While concerned entirely with the phenomenon of looking and being looked at, the space is limited to the bourgeoisie and aristocracy of Paris, and relatively inaccessible to the lower-middle class, sex workers, and numerous other maginalized identities. Furthermore, its sumptuous and excessive ornamentation may be gendered feminine when considered from the perspective of the École des Beaux-Arts ideology. The Nouvel Opéra, usually referred to as the Palais Garnier, is an example of the myth of the “Great Artist” discussed by Linda Nochlin in her seminal 1971 paper, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”20 Since the construction of the Nouvel Opéra, Charles Garnier has been treated in many scholarly writings as an architectural genius,21 or “prototype of the Romantic artist,”22 an attitude Christopher Mead upholds in Charles Garnier’s Paris Opéra (1991). Mead’s narrative has fed into the development of the canon of architectural history which all too often privileges the contributions of male architects while not just ignoring but actively erasing those of women. It is partly for this reason that I use the term Nouvel Opéra (which was used by Garnier and his contemporaries) in place of Palais Garnier.

IV: Critical Feminist Analysis of The Grand EscalierThe Nouvel Opéra’s Grand Escalier actively enforces the centering of the flâneur and masculine social myths through its architecture and treatment of space, emphasizing hierarchy and ostentatious ornamentation to provoke superficial self-reflection and an acute awareness of being seen. This centrally-located foyer was designed following principles of the architecture of department stores,23 with a vast atrium, palatial scale, and the prioritization of clear lines of sight across the space. However, the architecture of the department store and the Grand Escalier differ on two levels: firstly, Garnier did not flaunt his modern building technologies but rather chose to cover them up with masonry and ornament to emphasize luxury and extravagance. Secondly, instead of selling merchandise, the Grand Escalier sold social mobility—or rather, framed itself as such. Here, I build off a line of argument introduced by Kathleen James-Chakraborty, in which she argues that “the monumental staircase… replaced the imperial court as the center of socially ambitious Paris.”24 When considered as a center of social capital, the Opéra becomes sooner comparable to the Palace of Versailles. Both are iconic Parisian palaces: one presented as public, one inherently private. The Opéra’s adoption of Versaille-esque Baroque detailing demonstrates the movement from rigid class-based hierarchy to gender- and social-based hierarchy in Second Empire Paris.

Situated centrally within the Nouvel Opéra, the Grand Escalier is the major circulation space that provides access to the loges, the general admission seating, the entry and exit, and numerous lounges and foyers. It is the heart of the building, architecturally and symbolically. Saturated in rich marbles of green, white, red, bronze, and pink, with accents of gold spattered throughout, the Grand Escalier is fundamentally hierarchical in its structure and ornament (although not in the way earlier Rationalist architects expressed these same ideas: see the work of Étienne-Louis Boullée and other Enlightenment-era Rationalists, who may sooner be branded Neoclassicists). Tiers of arches supported by stylized double columns of the Ionic order give rise to an inward-sloping ceiling painted in the style of baroque Roman and Genovese palaces and crowned by a square skylight.25 A double flight of steps rise from the Members’ Rotunda below the foyer before doubling back on themselves, guiding the visitor up to the doors of the auditorium in a widening ascent, then forking into two narrower flights that lead up to the loges (fig. 2).26 This narrowing of the staircase accompanying the ascent to aristocratic space points toward the privilege of visibility given to the upper class but glosses over the masculine orientation of this privilege.

Figure 2. Pierre André Leclercq, Paris l'Opéra Garnier: Le Grand Escalier, 2015. Photography.

The Grand Escalier’s centering of the flâneur goes hand-in-hand with the veiling of the Parisienne. As James-Chakraborty suggests, “a major function of the Opéra was to display young women'' who were frequently veiled, treated as the objects and indicators of status for the men who accompanied them.27 Just as in the streets of Paris, the Grand Escalier acts as a space of exhibition and enforcement of gender roles. These gender roles are rigid not just in their enforcement of who is allowed to experience public space, but what constitutes male or female in the first place. Throughout this paper, I have discussed gender and sexuality in terms aligned with a gender binary, assuming “men'' and “women'' are entirely definitive and mutually exclusive identities. Of course, nonbinary and queer individuals existed in Second Empire Paris, but their historical erasure as well as their contemporary enforcement of the gender binary renders their existence nearly obsolete, largely limited to the imagination of scholars.

On a symbolic level, the Grand Escalier functions as a metaphor for social mobility. Reading stairs in this way may be low-hanging fruit, but in the case of the Nouvel Opéra, where class distinctions are so central to the architecture, the Grand Escalier’s symbolism cannot be ignored. Considering class as well as gender, the Grand Escalier as a symbol of social mobility describes the privileging of the male experience and the subjugation of the female; while both men and women can ascend the steps, it is only men who may do so alone. The woman is effectively a possession of the man, dependent on his social and class ranking; her own social power is limited to her ability to uphold or reject her social responsibility, which in the end only affects herself. On a physical level, the Parisienne may well ascend the steps alone—the Amazone signals the possibility of this—but her duty of social responsibility prevents this level of autonomy. The notion of publicity is central to the Escalier, the main portion of which exposes those passing through it to numerous levels and a 360 degree radius. Like the streets of Paris, social responsibility is imposed on all and regulated by all. In a formal sense, the Escalier is self-conscious, turning in on itself between the basement and ground floor, inspiring this same awareness of the self within its visitors. In this way, it acts similarly to Jeremy Bentham’s eighteenth century Panopticon prison design.

V: ConclusionThe Nouvel Opéra, and specifically the Grand Escalier, remains a milestone in the “living” canon of architectural history.28 Certainly, the building is remarkable in its massive size, sumptuous ornamentation, and monumental siting within the city of Paris. Moreover, it was subtly radical for its time, adapting the aristocratic architectural language of the Baroque and Rococo movements (historically reserved for monumental spaces of aristocracy, wealth, and political/cultural power) to a public monument intended for a variety of classes. However, its progressive character is limited to class, and even at that, it was far from a democratizing space. It does serve, however, as a valuable example from which the general social and cultural climate of Second Empire Paris can be evaluated, consolidating Parisian social culture within one specific site, evaluable as a microcosm of wider Paris. As a primary source, the Grand Escalier is saturated with meaning derived from its context; Haussmann’s reconstruction, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the doctrine of separate spheres, and contemporary gendered attitudes around the act of looking inform an art historical reading of the architecture as a urban centerpiece firmly solidified in the canon.

Endnotes

Kathleen James-Chakraborty, “Chapter 14: Paris in the Nineteenth Century,” in Architecture Since 1400, 273-289. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 285.

Van Zanten, Building Paris: Architectural Institutions and the Transformation of the French Capital, 1830-70. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 43.

James-Chakraborty, “Paris in the Nineteenth Century,” 278.

James-Chakraborty, 281.

Marni Kessler,“Dusting the surface, or the bourgeoise, the veil, and Haussmann’s Paris,” in The Invisible Flaneuse? Gender, Public Space, and Visual Culture in Nineteenth-Century Paris. Eds. Aruna D’Souza and Tom McDonough, 46-64. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006), 51.

Du Montcel, “Opera de Paris,” 7; Skelly, Realism and the Social History of Art, September 16, 2021.

James-Chakraborty, “Paris in the Nineteenth Century,” 280.

Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life,” In The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays. Trans. and ed. Jonathan Mayne. (Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1964), 5.

Paul P. Cret, “The École Des Beaux-Arts and Architectural Education,” Journal of the American Society of Architectural Historians 1, no. 2 (1941): 3.

Stephane Kirkland, Paris Reborn: Napoleon III, Baron Haussmann, and the Quest to Build a Modern City. (New York: St Martin’s Press, 2013), 249.

James-Chakraborty, “Paris in the Nineteenth Century,” 274.

Paula J. Birnbaum, Women Artists in Interwar France: Framing Femininities. (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011), 4.

Kessler, “Dusting the Surface, or the bourgeoise, the veil, and Haussmann’s Paris,” 51.

Kessler, 50.

Kessler, 51.

Kessler, 51.

Kessler, 50.

Griselda Pollock, Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism, and Histories of Art. (London and New York: Routledge, 1988), 76.

Charles Garnier, Le Nouvel Opéra. Nouv. éded. Librairie de l'Architecture et de la Ville. (Paris: Linteau, 2001), 295.

Linda Nochlin, Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays. (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1988),153.

Christopher C. Mead, Charles Garnier’s Paris Opéra: Architectural Empathy and the Renaissance of French Classicism. (New York: Architectural History Foundation, 1991), 113.

Kirkland, “Paris Reborn,” 193.

James-Chakraborty, “Paris in the Nineteenth Century,” 285.

James-Chakraborty, “Paris in the Nineteenth Century,” 286.

Du Montcel, “Opera de Paris,” 16.

Du Montcel,15.

James-Chakraborty, “Paris in the Nineteenth Century,” 287.

Martin Bressani, and Peter Sealy. “The Opéra Disseminated: Charles Garnier’s Le Nouvel Opéra de Paris (1875-1881).” In Studies in the History of Art 77, 195-219. National Gallery of Art, (2011): 212.

Bibliography

Baudelaire, Charles. “The Painter of Modern Life,” In The Painter of Modern Life and Other Essays. Translated and edited by Jonathan Mayne. Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1964.

Birnbaum, Paula J. Women Artists in Interwar France: Framing Femininities. Farnham: Ashgate, 2011.

Bressani, Martin, and Peter Sealy. “The Opéra Disseminated: Charles Garnier’s Le Nouvel Opéra de Paris (1875-1881).” In Studies in the History of Art 77, 195-219. National Gallery of Art, 2011.

Cret, Paul P. “The École Des Beaux-Arts and Architectural Education,” Journal of the American Society of Architectural Historians 1, no. 2 (1941): 3–15.

Garnier, Charles. Le Nouvel Opéra. Nouv. éded. Librairie de l'Architecture et de la Ville. Paris: Linteau, 2001.

James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. “Chapter 14: Paris in the Nineteenth Century,” in Architecture Since 1400, 273-289. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Kaldor, Andras. Opera Houses of Europe. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1996.

Kessler, Marni. “Dusting the surface, or the bourgeoise, the veil, and Haussmann’s Paris,” in The Invisible Flaneuse? Gender, Public Space, and Visual Culture in Nineteenth-Century Paris. Edited by Aruna D’Souza and Tom McDonough, 46-64. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006.

Kirkland, Stephane. Paris Reborn: Napoleon III, Baron Haussmann, and the Quest to Build a Modern City. New York, NY: St Martin’s Press, 2013.

Mead, Christopher C. Charles Garnier’s Paris Opéra: Architectural Empathy and the Renaissance of French Classicism. New York, NY: Architectural History Foundation, 1991.

Nochlin, Linda. Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1988.

Pollock, Griselda. Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism, and Histories of Art. London and New York: Routledge, 1988.

Skelly, Julia. Realism and the Social History of Art. McGill University, Montréal, September 16, 2021.

Tezenas du Montcel, Benedicte. Opera de Paris. Collection Compas, No 3. Translated by Amanda Elvines. Clermont-Ferrand: Instant durable, 2000.

Van Zanten, Building Paris: Architectural Institutions and the Transformation of the French Capital, 1830-70. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.