Refiguring Wax: Allusions to Votive Offerings, Funerary Effigies, and Anatomical Models in the Waxworks of Paul Thek and Robert Gober

Author: Isabelle Hawkins, McGill University

Editor: Dahlia Labatte

Paul Thek’s (1933–1988) Technological Reliquaries, completed in New York between 1964 and 1967, consist of wax meat pieces and human limbs enclosed in Plexiglas cases. Robert Gober’s (b. 1954) Untitled wax legs, which he created in New York beginning in 1989, protrude from gallery walls, often outfitted with hair, pants, and shoes. At first glance, these pieces are so striking, horrifying, and singular, that they seem completely unprecedented. Of course, they are not. This project re-examines these sculptures through their mediums, connecting them to long histories of wax votive offerings, wax funerary effigies, and wax anatomical models to deepen the discussions of faith, sickness, and death that surround Thek and Gober’s art. Recent art historical interest in votive offerings and anatomical models has yet to substantively connect these practices with Thek and Gober’s works. Scholarship on Thek’s reliquaries and Gober’s legs often mentions wax as a brief aside or when it poses a challenge to conservation. This paper argues that these artists’ choice of medium is not secondary or incidental, but is instead fundamental to the themes in their work and the emotions it elicits. While I have examined every photograph and in-person account that is available, I have not seen any of Thek’s or Gober’s works in person. My engagements with votives, effigies, and anatomical models are limited by the same constraints; I have not seen these items in person. Many objects I discuss, especially votives, have been destroyed or lost to time, so I have relied on written descriptions and photographs whenever possible.

Votive offerings precede Christianity and continue to be dedicated to the present day. These objects are offered to a divinity or saint to ask for a grace or to give thanks for a received grace.1 They were typically given in places of pilgrimage, churches, chapels, and shrines, and could consist of any material including wax, wood, and stone.2 Anatomical votives were modeled from a body or a body part that corresponded to the favour being asked. Archeological finds suggest that anatomical votives were most popular in Greece between the fifth and third centuries BC.3 In Italy, they appeared in the fourth century BC, peaking during the third and second centuries, before declining by or during the first century BC.4 Across the Mediterranean, these objects fell out of fashion before the turn of the first millennium, though they continued to be dedicated in smaller quantities and never disappeared, even while their form, material, and ritual context have undergone many changes.5 In Renaissance Italy, wax became the most common medium for votive offerings. As wax could be cast from the votary’s body, the verisimilitude that was possible in this medium strengthened the emotional ties between votary and votive.6 However, most votives that were dedicated in this period were mass-produced by artisans, probably from shops located near shrines.7 In Florence, these kinds of offerings were so popular that they created an industry from the thirteenth to the eighteenth century.8 This practice ended in 1786 when Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor from 1790 to 1792, ordered the clergy to free the churches of all votive offerings under the pretext that they “blocked the view of the frescos.”9 In spite of this abrupt ban, votives are still offered, though to a lesser extent, in sites of pilgrimage, churches, chapels, and shrines across the world.

The longstanding association between wax and death is due, in large part, to funerary effigies and death masks. Like votives, funerary sculptures have existed for millennia. Death masks have been preserved from Asiatic, European, Middle Eastern, African, and Mexican antiquity.10 In Ancient Rome, cerae (wax effigies) originated in patrician funerary observances because the hot climate and length of the funeral put the condition of the real body at risk.11 For these effigies, maximum fidelity to life was the “first principle.”12 This form of funerary sculpture “remained essentially constant over a period of more than one and a half millennia.”13 In Latin Christianity from the beginning of the thirteenth century, the exhibition of the dead showing the face became intolerable, so the wax effigy took the body’s place.14 In France, England, Florence, and Venice, wax effigies were intermittently popular among the ruling classes and nobility from the fourteenth century to the eighteenth century.15 Even among the lower classes in Europe, the objects involved in funerals were deliberately ephemeral, and wax candles were thought to be a worthwhile expenditure.16 Through death masks, effigies, and candles, wax has persisted as an essential part of funerary rituals.

The creation of the first anatomical models formed from coloured wax is generally credited to Gaetano Giulio Zumbo.17 Zumbo was a Sicilian abbott who learned to cast and model wax to produce votive objects while he was a student at a Jesuit college in Sicily.18 In 1695, Zumbo moved to Genova where he collaborated with a French surgeon, Guillaume Denoues, to reproduce his dissections in wax.19 Like subsequent anatomical waxes, Zumbo’s sculptures were modeled from cadavers.20 The first center for wax anatomical modeling was in Bologna, and in the late eighteenth-century, the center of wax modeling in Italy shifted from Bologna to Florence.21 In 1761 in Venice, Giovanni Battista Morgagni published De Sedibus et Causis Morborum which stressed the importance of organ pathology and surgery.22 These new discoveries created an urgent need to instruct trainee surgeons in anatomy. Anatomical waxes would become the preferred prop for medical teaching.23 By the turn of the century, Florentine modeling was at its height, and waxworks could be found in studios across Europe.24 Though anatomists and modelers used engravings as templates,25 it is estimated that over 200 bodies were needed to create one full-body sculpture.26 These bodies were either copied in clay or rough wax or were dissected, cast in plaster, and used as moulds for wax specimens.27 At the beginning of the nineteenth century, production gradually shifted from depicting normal anatomy to demonstrating disease processes, especially in the skin.28 Wax moulages excelled in reproducing dermatological or venereal afflictions as they were cast directly from patients.29 Unfortunately, the invention of colour slide photography and the telephoto lens in the 1950s rendered moulage production largely obsolete.30 Though many anatomical waxes have been lost to time, several have been preserved in collections across the world, attracting the attention of historians and art historians alike.

Paul Thek was born in 1933 in Brooklyn, New York.31 He spent most of his childhood in Long Island before attending Cooper Union, a private college, to study drawing and painting.32 Thek graduated in 1954, moved to Miami, then returned to New York a few years later.33 In the summer of 1963, Thek and his partner, Peter Hujar, took a trip to Palermo, Italy where they visited the Capuchin Catacombs. In a 1965 interview with Gene Swenson, Thek described touching a piece of dried thigh, and said he “felt strangely relieved and free [...] we accept our thing-ness intellectually but the emotional acceptance of it can be a joy.”34 The following year, he began creating his Technological Reliquaries, the sculptures that would skyrocket him to New York art world fame. Thek executed this series over a three-year period, abandoning the project in 1967 when he moved to Europe and focused on painting, writing, and a mode of installation art that he called “Processions.”35

It is easy to see how the “thing-ness” of that dried thigh in Palermo is so often cited as the inspiration for Thek’s reliquaries. Thek’s bloody, sinewy, and disfigured pieces of meat conjure a “pure abjection” that shocks and revolts.36 The objects’ matted hair enhances their realism and magnifies the disgust they evoke (fig. 1). Thek found hair to have “an extremely beautiful-ugly quality, very akin to nausea.”37 The homemade glass cases that enclose the meat heighten and stall the moment of shock, leaving the viewer no opportunity to touch the flesh and overcome their fear.38 Thek sought to create something that “seemed real.”39 He explained that “The world was falling apart [...] and I’d go to a gallery and there would be a lot of fancy people looking at a lot of stuff that didn’t say anything about anything to anyone.”40 The vivid horror that Thek’s pieces elicit could only be generated with wax. He appreciated wax for its “excessive resemblance to flesh.”41 Wax moves, gives way under your fingers, warms upon touch, and flows easily into molds—it is almost alive. As Georges Didi-Huberman aptly described it, wax is “the material of all resemblances.”42 Wax’s plasticity, instability, fragility, and sensitivity to heat “suggests the feeling or fantasy of flesh.”43 Human figures in wax are so uncanny because they resemble us too closely, though their stillness, their lifelessness, suggests that they are not our double but are instead our opposite.44 That said, it is impossible to verify with certainty that a wax figure is not alive, and this ambivalence is horrifying.45 Wax always goes too far; it produces a resemblance that is too radical, too unmediated, and too “real.”46 This is why Thek’s reliquaries shock: they are objects of grotesque abjection, and are consequently too real.

Thek’s reliquaries were exhibited three times and are consequently often divided into three parts. However, for this paper, I will make use of Oliver L. Schultz’s four categories that account for the sculptures’ aesthetic and thematic shifts.47 The first category is “human” pieces created between 1964 and 1965 that portray distinctly human flesh, often with skin (fig. 2).48 They are contained by glass boxes, some of which have yellow grids painted on their exteriors (figs. 1 and 2).49 The second category, executed between 1965 and 1966, is the “animal” pieces that are less square and more “like large portions of the limbs of monsters” (fig. 3).50 They are enclosed in clear or neon-tinted Plexiglas mounted on melamine-paneled bases.51 The third category, the “posthuman” reliquaries, was shown at the Pace Gallery in 1966 and consists of distorted and disfigured meat within elaborate boxes of DayGlo yellow Plexiglas, some of which feature hinged melamine enclosures (fig. 4).52 Lastly, the “figurative” meat pieces created between 1966 and 1967 consist of human limbs last cast from Thek’s body and enclosed in clear Plexiglas cases (fig. 5).53

Thek was raised in the Catholic Church and remained faithful until his death. In 1969, he wrote to a friend, complaining that he felt sapped by serving “two masters,” religion and the art world.54 Thek references Christianity by titling his works “reliquaries” and suggesting sacrality and “auratic inaccessibility” by enclosing his sculptures in display cases.55 Additionally the flesh in all of Thek’s 1964 reliquaries, and many past 1964, show no sign of decay (figs. 1 and 2). This is a classic miracle associated with saints—the “incorruptibility” of their bodies.56 The leather armor on Thek’s “figurative” pieces also evokes the armour worn by Renaissance archangels (fig. 6).57 The patterning on a hand sculpture of the same period recalls butterfly wings, which symbolize transformation and resurrection in Christianity (fig. 7).58 However, the scope of Thek’s religious allusions can only be fully grasped when the reliquaries are examined through their mediums.

In the Medieval and Early Modern periods, bees were thought to reproduce without mating.59 Their ostensible chastity made them ripe for comparisons to the Virgin Mary and Christ. The connection between beeswax and Christ is made literal in Vincenzo Bonardo’s 1586 treatise on the sacramentals known as Agnus Dei. He states “Moreover, just as the bee […] makes the honey and the wax and produces its offspring without being inflamed by any libidinous heat, so the glorious Virgin […] without human help, by the virtue of the Holy Spirit, produced this precious honeycomb that is Christ.”60 Thek himself even connected the reliquaries to the flesh of Christ, saying “very clearly I saw this meat on a wall, almost crucified.”61 For Cynthia Hahn, Thek’s Birthday Cake (fig. 8) evokes the sacrament of the Eucharist, as its shape and name brings the ritual of consuming the body of Christ to mind.62 Through their medium, display, and form, Thek’s reliquaries evoke the body of Christ.

Anatomical votives take the shape of human bodies or limbs. Thek’s “figurative” reliquaries echo the form of these offerings, and were, like many, cast from their owner’s body. Thek created these pieces when he was trying to figure out how to make a full body cast.63 He stated “I had a studio filled with imperfect limbs covered with different-colored wax, to test the tinting, so it was an easy, natural thing to make use of them.”64 In “The Votive Scenario,” Christopher Wood argues that the anatomical votive is connected to the concept of sacrifice.65 Votives are tied to their votary because they are either cast from the votary’s body or are bought “off the rack,” and tethered to the votary through the ritual of purchasing it, transferring it to the shrine, and dedicating it.66 Because these limbs belong to their votaries, they can be read as models of amputated extremities, sacrificed to a saint as the price of a favour.67 The possibility that votives represent not healed but “irreversibly damaged limbs,” is supported by the evidence of real amputated body parts at some shrines.68 Thek’s “figurative” reliquaries lend themselves easily to this interpretation. At the place where an arm or leg should connect to a body, Thek’s limbs display fresh, bloody wounds (fig. 9). These sculptures are not merely parts, but “a limb that has been hacked from the body to which it once belonged.”69 Though Thek’s reliquaries ressemble votive offerings, their bloodiness suggests that they may instead be severed limbs, objects which were also dedicated at some shrines.

While Thek’s “figurative” pieces certainly resemble votives, another possibility can be inferred from the name given to these sculptures. “Reliquaries” denotes the container for a Relic. Though it seems that Thek’s reliquary is his glass case while his Relic is the flesh inside, the ambiguous title and object permits a different reading. Votive offerings were proximate to relics as they ornamented shrines, ratifying the authenticity of the Relics to visitors.70 As Thek’s title does not confirm that a Relic is present, it is possible that the flesh inside his cases are instead votive offerings.

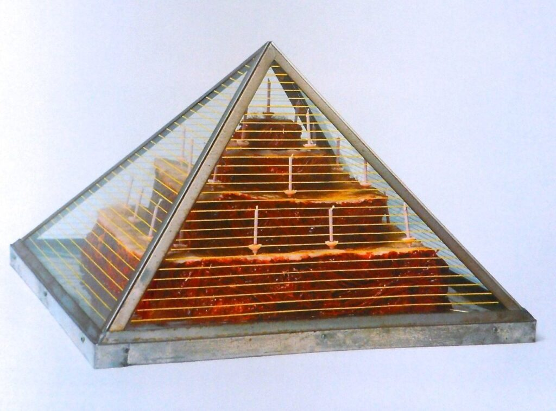

According to Oliver L. Schultz, Thek’s meat pieces “paved the way” for his 1967 full-body effigy, The Tomb (fig. 10).71 This would be the last work he produced in the United States before moving to Europe, and foreshadows his subsequent turn towards installation art.72 The Tomb, exhibited at the Stable Gallery, consisted of a ten-foot tall pink wooden pyramid (fig. 11).73 Inside the tomb, displayed horizontally, was Thek’s wax life-sized effigy. The body was dressed in a suit jacket, jeans, and cowboy boots, while its head was raised on two pillows with a black, or blue,74 tongue protruding from its mouth.75 The effigy was surrounded with pages of handwritten text, a few photographs, and another pillow, suggesting perhaps that visitors to the tomb should kneel.76 Thek also severed the fingers from the right hand of the corpse, rendering the wounds in a stark red pigment and placing the fingers in a pouch that hung on an interior wall.77 Not only did this piece resemble a funerary effigy, but it also elicited the same reaction as a funerary effigy. One reviewer for the exhibition wrote that “visitors tend to tiptoe reverentially up to the glass door of the ‘tomb’ and speak in whispers.”78 The sculpture therefore functions almost as a performance piece, though the body evoked is not the living body of the artist, but is instead his corpse. In “Biopolitical Effigies,” Melina Tomic argues that this tomb is a subversion of “the sanitised notion of a wax effigy.”79 The effigy’s darkened tongue can be read as a sign of putrefaction and volatility, and thus corrupts the effigy with traces of rot.80 Even while invoking a form whose history can be traced to antiquity, Thek’s sculpture defects from typical effigies by exhibiting signs of decay.

Like anatomical waxes, Thek’s reliquaries exhibit the muscle, tissue, and sinew contained by skin. Thek’s “human” sculptures are cut into perfect cubes, evoking the precise and methodical incisions of a dissector’s blade. Though anatomical waxes can depict internal organs, Thek’s pieces picture only the skin and the layers immediately beneath it. Though internal organs are absent, the reliquaries still invoke the body’s internal processes by reproducing the transmission of fluids that is directed by several organs. Untitled from 1964 (fig. 12), for example, consists of two meat pieces with small metal tubes that protrude from the meat and connect to valves that stretch outside the glass case. The red pigment in these tubes suggests blood.81 As blood is “a kind of system for conveying the body’s internal signals,” these tubes also evoke the transfer of matter or information.82

Thek’s “human” reliquaries do not resemble parts of a cadaver.83 They shine and glisten, and their skin is pink and flushed with blood, with no sign of decay. The pieces’ liveliness echoes the vitality of Florentine anatomical venuses from the nineteenth century. These sculptures of reclining women were called “venuses” as a reference to the Venus de Medici, a statue created by an unknown Greek sculptor at the beginning of the 3rd century BC.84 These venuses are beautiful, with bright eyes and flushed skin.85 Clemente Susini and Guiseppe Ferrini conceal every sign of death in their anatomical model, the Medici Venus (fig. 13). The pearl necklace on this venus covers a cut under her throat from which she could be dismounted.86 This cut would confirm that she is dead, and is hidden to maintain the illusion of life. Like the Medici Venus, Thek’s “human” reliquaries refuse to give any indication that they are no longer alive.

The “animal” and “posthuman” reliquaries show the body in more advanced states of decay. Thek’s creative decision has its own counterpart in anatomical waxes. English waxes, particularly those of Joseph Towne, are practical, crude, true, and lifeless.87 Their pale faces, glazed eyes, and grimaces “evoke the impression of being faced with a cadaver.”88 Zumbo’s models were equally committed to portraying cadavers honestly. His waxes “depict human bodies in the grip of the physical anarchy unleashed by decay.”89 Unlike subsequent waxes, the interior of the body in Zumbo’s models is not exposed by the blade, but by the biological process of decomposition.90 Zumbo’s Wax Model of the Head (fig. 14), for example, exhibits blood dripping from the nose. This inclusion was entirely unnecessary, and it demonstrates Zumbo’s commitment to portraying his subjects as he encountered them. Like Towne and Zumbo, Thek’s “animal” and “posthuman” reliquaries exhibit the gruesome reality of decay.

Thek’s reliquaries are so striking and original that it is difficult to posit one explication of what they represent, mean, and do. Their confusing, complex, and contradictory properties have allowed me to draw out their allusions to Christ, sacrifice, effigies, organs, anatomical venuses, and the waxworks of Towne and Zumbo. Though these comparisons rely on observation, they are grounded most essentially in the medium of wax.

Robert Gober was born in Wallingford Connecticut.91 From 1972 to 1976, he studied fine arts and literature at Middlebury College in Vermont before moving to New York permanently after graduation.92 Early in his career, Gober earned a living as a carpenter, handyman, and artist’s assistant.93 His first solo show was at the Paula cooper gallery in 1984, and by 1990, he was an established figure in the New York art world.94 In the 1980s, Gober experimented in several mediums, focusing most intently on transformations and iterations of urinals, sinks, playpens, cribs, beds, and armchairs.95 He was interested in “emblems of transition.”96 These are objects that transform you: “Like the sink, from dirty to clean; the beds, from conscious to unconscious.”97 As these objects are used and acted upon by bodies, the lack of a human bodily presence is disquieting. Gober began making his wax legs from casts of his own body in 1989, and would continue working from the same motif throughout the 1990s.98 It is fitting that he would choose to sculpt his legs from beeswax, a material that is associated with metamorphosis because it can “form and liquify.”99

Gober was a gay man living in New York during the AIDS crisis. In 1984, he began volunteering at the Gay Men’s Health Clinic, first as a Buddy, then as a Crisis Intervention Worker.100 Gober recalls “constantly wash[ing] his hands” out of fear of becoming infected.101 His interest in sinks and drains “partially grew out of that experience.”102 Like Thek, Gober was raised in the Catholic Church, but unlike Thek, he lost his faith, and declared in 1989 that he was relieved to have left the Church.103 Gober was openly critical, calling the Church “a very sick place [...] a hypocritical institution [...] where I got my initial inspiration of perversity.”104 In spite of this distaste, allusions to Catholicism permeate his sculptures through their candles and their medium.

Though this analysis thus far has focused on anatomical votives, the votive use of wax is found most commonly in candles.105 Votive candles could be produced at the site of a shrine and purchased by pilgrims to be lit in the church.106 Votive candles could also be custom made, corresponding in size or weight to the scale of the favour being asked or to the person asking the favour.107 Candles are also significant in Catholic ritual, particularly the Paschal ritual, where the Paschal candle symbolizes the body of Christ.108 Though they are not shaped to resemble a human figure, these candles are treated like a body and are pierced with five grains of incense, representing the five wounds of Christ, while a prayer referencing his crucifixion is recited.109 These candles oscillate between representation and real. While they do not imitate Christ’s physical form, these candles invoke his symbolic and sacred presence. Beginning in the tenth century, Exultet rolls, containing the chant read by the priest, were used in southern Italy.110 This chant contains a passage that mentions bees: “O holy Father, accept this candle, a solemn offering, the work of bees and of your servants’ hands, an evening sacrifice of praise, this gift from your most holy Church.”111 Christ’s resurrection is then acted out as the Paschal candle is used to ignite the other candles in the church.112 Here, the flame represents the Holy Spirit which proceeds from Christ to illuminate the apostles, the prophets, and all the faithful of the Church.113 Even in secular contexts, candles remain symbols of mourning. They are prominent at vigils, funerals, and grave sites. Given Gober’s experience during the AIDS crisis, the candles on his legs may intend to honour a loved one lost to AIDS (fig. 15). According to Kristen Hutchinson, these candles are optimistic because they are unlit, signifying that a death has not yet occurred.114 This expresses “hope for recovery in the face of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.”115 According to Gober, his candles imply “resuscitation.”116

The pallor of Gober’s legs imbues them with a lifelessness that is similar to that of a funerary effigy. In his studio, Gober bleached his beeswax. This technique allows the wax to change colour without removing its natural colourants.117 The resulting skin is as pale and bloodless as that of a corpse. In “The Materiality of Death in Early Modern Venice” by Alexandra Bamji, she argues that Venetian effigies sought verisimilitude to the dead rather than the living body.118 The stubble on the death mask of doge Alvise IV Mocenigo, for example, echoes the effect produced by skin retraction and dehydration on the chin of a corpse.119 The hairs that Gober meticulously and individually inserts into his legs brings to mind the real hairs that were also inserted into Renaissance effigies.120 These hairs suggest “not life, but the make-believe life that is a mortician’s obsession.”121 Though Gober’s legs appear dead, they show no signs of decomposition. By stalling their inevitable decay, Gober plays with time and suspense. Gober’s candles, which poke upright out of legs, also foster anticipation. If the candle is lit, the wax will melt, and the leg will liquify. These candles function as unlit bombs, “holding time in abeyance in a way that provokes anxiety and thrills.”122 The tension between life and death, intensified by these candles, also signifies resuscitation. In one sense, death seems to inhabit these legs, but in another, their form is intact, signifying that a death has not yet happened.

Unlike Thek’s reliquaries, Gober’s legs are not bloody. The clothes on his sculptures are pristine, and the shoes on their feet have been polished (fig. 16).123 Because these legs are seamlessly connected to gallery walls, is it not clear whether they have been dismembered or are still attached. While Thek’s “human,” “animal,” and “posthuman” reliquaries are cut open and laid bare, the only points of access to the interior of Gober legs are their drains (fig. 17). When they are read as wounds, these drains can be seen as a refiguration of the sores that were depicted in wax moulages. Though most moulagers kept the intricacies of their methods secret, the basic principle is that melted wax would be poured into a plaster mold which was cast from the patient.124 The wax would then be painted and embellished with hair and glass eyes.125 This technique was most commonly used to portray afflictions visible on the skin.126 The creation of the first wax moulage is generally credited to Franz Heindrich Martens, a German medical professor.127 Though there are no signs that he was influenced by Martens, in the early or mid-nineteenth century, the British wax modeler Joseph Towne also began creating wax moulages.128 By the end of his life, he had made about five-hundred sixty.129 In the following decades, the popularity of wax moulages grew.130 Given this context, Gober’s drains can be read as the sores or lesions that are symptomatic of AIDS. These drains allegorize “the societal anxiety about porous bodily boundaries as a site of contagion.”131 As they are open, they transform the body into a conduit that is weak and unable to fight the intrusion of illness.132 Gober thought of drains “as a window into another world,” one that is “darker and unknown.”133 Drains are sites of impure mixtures, “where one thing slips over another.”134 They are associated with waste and disease, and, like lesions, they provoke disgust.135 When read as sores or lesions, Gober’s drains are connected to both a tradition of wax moulage and the contemporary crisis of the AIDS epidemic.

Gober’s legs invoke votive and Paschal candles through their candles, imply resuscitation by leaving candles unlit, signify death through their pallor, and refer to wax moulages and the AIDS crisis through their drains. Because Gober’s legs are truer to life than Thek’s reliquaries, the absence of movement and vitality in these pieces is particularly unsettling.

Even though it has been, at times, the medium of choice for votive offerings, funerary effigies, and anatomical models, wax has remained unpopular in the visual arts, and has been largely ignored in art historical scholarship. Through their forms and material, Thek’s wax reliquaries and Gober’s wax legs refer to these earlier traditions. By unpacking the connections between these sculptures and their predecessors, I conclude that wax provides a rich and untapped angle through which Thek and Gober’s work can be analyzed and understood. Due to their use of wax and their precise replication of the human form, Thek’s reliquaries and Gober’s legs are remarkably realistic. However, the decay, pallor, and stillness that these works exhibit denies the presence of a live body. Simultaneously, these pieces are life-like and life-less.

Appendix

Figure 1, Paul Thek, Rundfahrt, from the Technological Reliquaries series, wood, mirror, wax, paint, resin, hair, metal, glass (with silkscreen), 1964, 21.6 x 21.6 x 12 cm., In Paul Thek : Untimely Bodies, 1963-1988, by Oliver L. Schultz, figure 1.12, Stanford, California: Stanford University, 2018.

Figure 2, Paul Thek, Untitled, from the Technological Reliquaries series, wax, metal, wood, paint, hair, cord, resin, and glass, 1964, 60.9 x 60.9 x 19 cm., Collection of Gail and Tony Ganz, In “An Artist in the Secular World: Paul Thek’s Relics,” by Paisid Aramphongphan, figure 11, Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2021.

Figure 3, Paul Thek, Untitled, from the Technological Reliquaries series, wax, bronze, Formica, Plexiglas, 1965, 42 x 55 x 24 cm., Kolodny Family Collection, https://www.artforum.com/events/paul-thek-11-249167/.

Figure 4, Paul Thek, Untitled, from the Technological Reliquaries series, wax, paint, melamine laminate, metal, Plexiglas, 1965-1966, 216 x 24.1 x 24.1 cm., Sammlung Falckenberg, Hamburg, In Paul Thek : Untimely Bodies, 1963-1988, by Oliver L. Schultz, figure 1.12, Stanford, California: Stanford University, 2018.

Figure 5, Paul Thek, Untitled, from the Technological Reliquaries series, wax, wood, metal, hair, plaster, paint, and Plexiglas with wig and fabric (lost elements re-recreated 2006), 1966-1967, 17 x 50.1 x 17 cm., Watermill Center Collection, https://www.lemonde.fr/culture/portfolio/2013/11/15/bob-wilson-ouvre-sa-chambre-au-public-au-coeur-du-louvre_3514441_3246.html.

Figure 6, Paul Thek, Warrior’s Arm, from the Technological Reliquaries series, wax, paint, leather, metal, wood, resin, and Plexiglas, 1966-67, 24.1 x 99.1 x 24.1 cm., Carnegie Museum of Art, https://artmap.com/whitney/exhibition/paul-thek-2010.

Figure 7, Paul Thek, Untitled, from the Technological Reliquaries series, wax, metal, paint, butterfly wings, Plexiglas, 1967, 23 x 23 x 87.5 cm., Museum Ludwig, Cologne, https://museenkoeln.de/portal/bild-der-woche.aspx?bdw=2008_21.

Figure 8, Paul Thek, Birthday Cake, from the Technological Reliquaries series, mixed media sculpture, 1964, 48.2 x 62.2 x 62.2 cm., https://greg.org/archive/2022/12/20/paul-theks-birthday-cake-of-flesh.html.

Figure 9, Paul Thek, Warrior’s Leg, from the Technological Reliquaries series, wax, metal, leather, paint, and Plexiglas, 1966-1967, 66.5 x 36 x 21 cm., Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/casualty-of-war-77169587/.

Figure 10, Installation view: Paul Thek, The Tomb, Stable Gallery, mixed media, 1967, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/24/biopolitical-effigies-paul-thek-and-lynn-hershman-leeson.

Figure 11, Installation view: Paul Thek, The Tomb, Stable Gallery, mixed media, 1967, In Paul Thek : Untimely Bodies, 1963-1988, by Oliver L. Schultz, figure 1.12, Stanford, California: Stanford University, 2018.

Figure 12, Paul Thek, Untitled, from the Technological Reliquaries series, wax, pigment, metal, hair and mixed media, ca. 1964, Des Moines Art Center, In Paul Thek : Untimely Bodies, 1963-1988, by Oliver L. Schultz, figure 1.12, Stanford, California: Stanford University, 2018.

Figure 13, Clemente Susini and Giuseppe Ferrini, Medici Venus, 1782, Museum La Specola, Florence, Italy, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Anatomical-Venus-wax-Courtesy-of-the-Museum-of-Natural-History-in-Florence-Photo_fig1_274557447.

Figure 14, Gaetano Zumbo, Wax model of the head (front view), ca. 1695, Museum La Specola, Florence, Italy, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0079612318301493.

Figure 15, Robert Gober, Untitled, wax, cloth, wood, leather and human hair, 1991, 31.3 × 26 × 95.3 cm., Whitney Museum of American Art, https://whitney.org/collection/works/7987.

Figure 16, Robert Gober, Untitled, wax, wood, leather, fabric and human hair, 1989-1992, 30 x 16 x 51 cm., Tate Modern, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/gober-untitled-t06658.

Figure 17, Robert Gober, Untitled, wax, wood, leather, fabric and human hair, 1991-1993, https://artviewer.org/i-am-a-problem-at-mmk-frankfurt-am-main/.

Footnotes

Roberta Ballestriero, “The Dead in Wax: Funeral Ceroplastics in the European 17th-18th Century Tradition,” in The Art of Death & Dying Symposium Proceedings (The University of Houston Libraries, October 24-27, 2012), 11.

Roberta Ballestriero, “Anatomical Models and Wax Venuses: Art Masterpieces or Scientific Craft Works?” Journal of Anatomy 216, no. 2 (2010): 223-224, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01169.x.

Jane Draycott and Emma-Jayne Graham, eds., Bodies of Evidence: Ancient Anatomical Votives Past, Present and Future (Routledge, 2017), 13-14.

Draycott and Graham, Bodies of Evidence, 13-14.

Draycott and Graham, Bodies of Evidence, 14.

Ittai Weinryb, ed., Agents of Faith: Votive Objects in Time and Place (Bard Graduate Center Gallery, 2018), 51.

Christopher Wood, “The Votive Scenario,” Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 59-60, no. 1 (2011): 223.

Ballestriero, “Anatomical Models and Wax Venuses,” 224.

Hanneke Grootenboer, “Introduction: On the Substance of Wax,” Oxford Art Journal 36, no. 1 (2013): 7.

Julius von Schlosser, History of Portraiture in Wax, trans. James Michael Loughridge (Jahrbuch der Kunsthistorischen Sammlungen des Allerhöchsten Kaiserhauses, 1911), 177.

Schlosser, History of Portraiture in Wax, 183 and 186.

Schlosser, History of Portraiture in Wax, 183.

Schlosser, History of Portraiture in Wax, 217.

Ballestriero, “The Dead in Wax,” 12.

Schlosser, History of Portraiture in Wax, 196, 201, 204-5; Ballestriero, “The Dead in Wax,” 12; Roberta Panzanelli, “Introduction: The Body in Wax, the Body of Wax,” in Ephemeral Bodies: Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure, ed. Roberta Panzanelli (Getty Publications, 2008), 17.

Alexandra Bamji, “The Materiality of Death in Early Modern Venice,” in Religious Materiality in the Early Modern World, ed. Andrew Morrall, Mary Laven, and Suzanna Ivanič (Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 131-132

Ballestriero, “The Dead in Wax,” 12.

Catherine Heard, “Uneasy Associations: Wax Bodies Outside the Canon,” in Disguise, Deception, and Trompe-l’oeil: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, eds. Leslie Boldt-Irons, Corrado Federici, and Ernesto Virgulti (Peter Lang, 2009), 235.

Heard, “Uneasy Associations,” 239.

Alessandro Riva, Gabriele Conti, Paola Solinas, and Francesco Loy, “The Evolution of Anatomical Illustration and Wax Modelling in Italy from the 16th to Early 19th centuries,” Journal of Anatomy 216, no. 2 (2010): 209, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01157.x.

Lyle Massey, “On Waxes and Wombs: Eighteenth-Century Representations of the Gravid Uterus,” in Ephemeral Bodies: Wax Sculpture and the Human Figure, ed. Roberta Panzanelli (Getty Publications, 2008), 89; Heard, “Uneasy Associations,” 240.

Samuel Alberti, “Wax Bodies: Art and Anatomy in Victorian Medical Museums,” Museum History Journal 2, no. 1 (2009): 11, https://doi.org/10.1179/mhj.2009.2.1.7

Riva et al., “The Evolution of Anatomical Illustration,” 216

Alberti, “Wax Bodies,” 11.

Massey, “On Waxes and Wombs,” 102.

Riva et al., “The Evolution of Anatomical Illustration,” 215.

Heard, “Uneasy Associations,” 241.

Heard, “Uneasy Associations,” 241.

Alberti, “Wax Bodies,” 11.

Heard, “Uneasy Associations,” 242.

Oliver L. Schultz, “Paul Thek : Untimely Bodies, 1963-1988” (PhD diss., Stanford University, 2018), 3.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 3.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 3.

Paul Thek, “Beneath the Skin: Interview with Paul Thek,” interview by Gene Swenson, ARTnews 65, no. 2 (April 1966): 66-67.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 4.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 6.

Cynthia Hahn, The Reliquary Effect: Enshrining the Sacred Object (Reaktion Books, 2017), 250.

John C. Welchman, ed., Sculpture and the Vitrine (Ashgate, 2013), 151.

Paul Thek, “Paul Thek: Real Misunderstanding,” interview by Richard Flood, Artforum 20, no. 2 (October 1981): 107.

Thek, interview by Richard Flood.

Hahn, The Reliquary Effect, 248.

Georges Didi-Huberman, “Wax Flesh, Vicious Circles,” in Encyclopaedia Anatomica: A Complete Collection of Anatomical Waxes, ed. Monika von Düring, Georges Didi-Huberman, and Marta Poggesi (Taschen, 1999), 1.

Didi-Huberman, “Wax Flesh, Vicious Circles,” 2.

Grootenboer, “Introduction,” 12.

Grootenboer, “Introduction,” 12.

Didi-Huberman, “Wax Flesh, Vicious Circles,” 4.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 33.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 33.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 33.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 33.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 33.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 33.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 33.

Paisid Aramphongphan, “An Artist in the Secular World: Paul Thek’s Relics,” American Art 35, no. 1 (Spring 2021): 41. doi.org/10.1086/713576.

Aramphongphan, “An Artist in the Secular World,” 44.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 37.

Aramphongphan, “An Artist in the Secular World,” 44.

Aramphongphan, “An Artist in the Secular World,” 45.

Mary Kirkpatrick, “Wax and Mortality: A Transhistorical Study on Wax in Artistic Depictions of Death” (MA thesis, Georgia State University, 2022), 12, https://doi.org/10.57709/28957184.

Mary Laven, “Wax Versus Wood: The Material of Votive Offerings in Renaissance Italy,” in Religious Materiality in the Early Modern World, ed. Andrew Morrall, Mary Laven, and Suzanna Ivanič (Amsterdam University Press, 2019) 41.

Thek, interview by Richard Flood.

Hahn, The Reliquary Effect, 253.

Thek, interview by Richard Flood.

Thek, interview by Richard Flood.

Wood, “The Votive Scenario,” 223.

Wood, “The Votive Scenario,” 223.

Wood, “The Votive Scenario,” 223.

Wood, “The Votive Scenario,” 223.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 92.

Wood, “The Votive Scenario,” 208.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 24.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 85.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 85.

Milena Tomic, “Biopolitical Effigies: The Volatile Life-Cast in the Work of Paul Thek and Lynn Hershman Leeson,” Tate Papers, 2015, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/24/biopolitical-effigies-paul-thek-and-lynn-hershman-leeson.

Dominic Johnson, “Modern Death: Jack Smith, Fred Herko, and Paul Thek,” Criticism 56, no. 2 (Spring 2014): 220.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 87.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 87.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 89.

Tomic, “Biopolitical Effigies.”

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 104.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 25

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 30.

Schultz, “Paul Thek,” 55.

Ballestriero, “Anatomical Models and Wax Venuses,” 230.

Ballestriero, “Anatomical Models and Wax Venuses,” 231.

Ballestriero, “Anatomical Models and Wax Venuses,” 231.

Ballestriero, “Anatomical Models and Wax Venuses,” 228.

Ballestriero, “Anatomical Models and Wax Venuses,” 228.

Ann Louise Kibbie, “Realism and Decay in Wax,” Configurations 25, no. 2 (Spring 2017): 175, https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/con.2017.0011.

Kibbie, “Realism and Decay in Wax,” 175.

Elissa Yukiko Weichbrodt, “Through the Body: Corporeality, Subjectivity, and Empathy in Contemporary American Art” (PhD diss., Washington University, 2013), 62.

Weichbrodt, “Through the Body,” 62.

Guggenheim New York, “Robert Gober,” Collection online, accessed December 10th, 2024, https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/artist/robert-gober

Weichbrodt, “Through the Body,” 62.

Elisabeth Sussman, Robert Gober: Sculptures and Installations, 1979-2007 (Schaulager, 2007), 20.

Robert Gober, “Robert Gober,” interview by Craig Gholson, BOMB, October 1, 1989, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/1989/10/01/robert-gober/.

Gober, interview by Craig Gholson.

Weichbrodt, “Through the Body,” 64.

Monica Ines Huerta, “Encountering Mimetic Realism: Sculptures by Duane Hanson, Robert Gober, and Ron Mueck” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2010), 130.

Jongwoo Jeremy Kim, Queer Difficulty in Art and Poetry: Rethinking the Sexed Body in Verse and Visual Culture (Routledge, 2017), 144.

Jongwoo, Queer Difficulty in Art and Poetry, 144.

Jongwoo, Queer Difficulty in Art and Poetry, 144.

Gober, interview by Craig Gholson.

Gober, interview by Craig Gholson.

Weinryb, Agents of Faith, 50.

Weinryb, Agents of Faith, 50.

Weinryb, Agents of Faith, 50.

Kirkpatrick, “Wax and Mortality,” 13.

Kirkpatrick, “Wax and Mortality,” 13.

Kirkpatrick, “Wax and Mortality,” 13.

Kirkpatrick, “Wax and Mortality,” 14.

Kirkpatrick, “Wax and Mortality,” 13.

Kirkpatrick, “Wax and Mortality,” 14.

Kristen Hutchinson, “The Body Part in Contemporary Sculpture: A Thematic Consideration of Fragmentation During the 1990s” (PhD diss., University of London, 2007), 192.

Hutchinson, “The Body Part in Contemporary Sculpture,” 192.

Hutchinson, “The Body Part in Contemporary Sculpture,” 192.

Huerta, “Encountering Mimetic Realism,” 131.

Bamji, “The Materiality of Death in Early Modern Venice,” 130.

Bamji, “The Materiality of Death in Early Modern Venice,” 130.

Ballestriero, “The Dead in Wax,” 13.

Jongwoo, Queer Difficulty in Art and Poetry, 144.

Jongwoo, Queer Difficulty in Art and Poetry, 143.

Hutchinson, “The Body Part in Contemporary Sculpture,” 173.

Thomas Schnalke, “A Brief History of the Dermatologic Moulage in Europe,” International Journal of Dermatology 27, no. 2 (March 1988): 134, 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1992.tb03256.x.

Schnalke, “A Brief History of the Dermatologic Moulage in Europe,” 134.

Schnalke, “A Brief History of the Dermatologic Moulage in Europe,” 135-136.

Schnalke, “A Brief History of the Dermatologic Moulage in Europe,” 136.

Schnalke, “A Brief History of the Dermatologic Moulage in Europe,” 137.

Schnalke, “A Brief History of the Dermatologic Moulage in Europe,” 137.

Schnalke, “A Brief History of the Dermatologic Moulage in Europe,” 137-140.

Tomic, “Biopolitical Effigies.”

Hutchinson, “The Body Part in Contemporary Sculpture,” 179.

Sussman, Robert Gober, 24.

David Joselit, “From the Archives: Poetics of the Drain,” Art in America, January 31, 2017, https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/from-the-archives-poetics-of-the-drain-63246/ .

Paula Owen, “Fabrication and Encounter: When Content is a Verb,” in Extra/Ordinary: Craft and Contemporary Art, ed. Maria Elena Buszek (Duke University Press, 2011), 126.