‘Art,’ ‘Nation’ + ‘Self’: The Self-Portrait of a Nation

Author: Antonella L. Pecora Ruiz, University of Toronto

Editors: Iris Bednarski and Courtney Squires

The ukiyo-e prints from the Edo period (1603-1868) not only captured the complexity of Japanese culture, everyday experiences, and aesthetic pleasures; they also played a crucial role in solidifying Japan’s national identity through their enduring presence in history. These prints reflect a historical and diverse range of societal dynamics in their depiction of Japan's political and social bodies during its significant transformation from the Edo to the Meiji period (1868-1912). By exploring the history of ukiyo-e prints, one will gain valuable insights into the societal norms, cultural tensions, and historical events that have shaped the evolution of Japanese art and identity, particularly in the context of Edo, present-day Tokyo. This exploration will shed light on how ukiyo-e prints contributed to a broader understanding of Japan's cultural narrative during a time of profound political and social change.

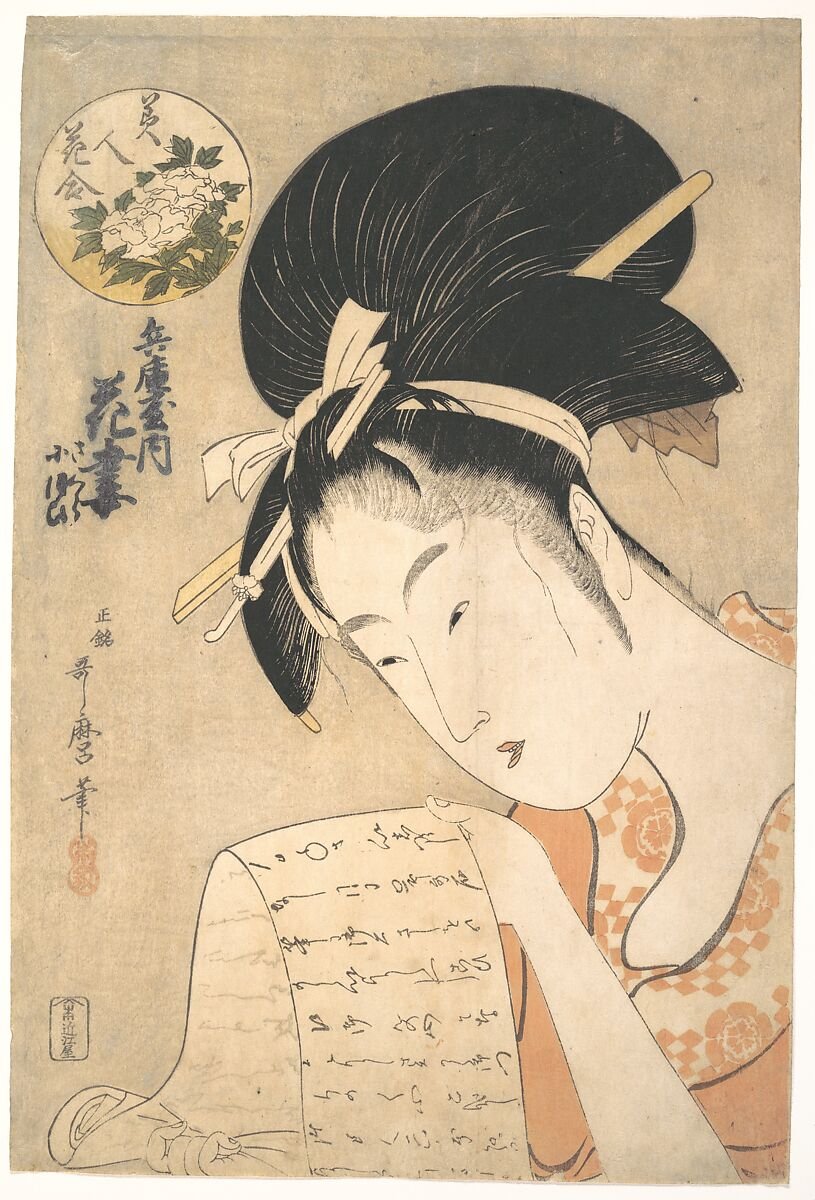

Artists from the Edo-period documented the development of Japanese life before significant interactions with the Western world. The themes present in ukiyo-e offer valuable insights into the societal norms, traditions, and daily activities of Japanese culture, providing a comprehensive understanding of the nation's way of life during this period. The style and content of the colourful woodblock prints, known as ukiyo-e, meaning “pictures of the floating world,” offer artistic representations of sensual pleasure, nature, cultural entertainment, and notable figures from the social and political elite. This tradition is exemplified by the works of Edo artists such as Sharaku (active 1794–1795),[1] famous for his portraits of Kabuki actors, and Suzuki Haranobu (1724-1770), who is known for portraying the friendly and erotic natures of the Edoites’ relationships.[2] The recurring themes of these prints reflect the Japanese lifestyle during the Edo period, and once paired with a critical analysis of ukiyo-e art, they offer profound and authentic insights into the civil society of the time. I will address the ukiyo-e works of Kitagawa Utamaro (active 1753-1806), with an emphasis on The Courtesan Hanazuma Reading a Letter (1790s) (fig. 1) to illustrate the range of societal norms and values that emerged from the political and social bodies of Japan during the Edo period, and ultimately, shaped the nation’s identity. With this analysis, I will underline how Kitagawa Utamaro unconsciously inspired the future generations of Japanese artists, and the nation, to embrace prints as a component of the nation’s identity. To do so, I will briefly evaluate two later works of ukiyo-e—Toyohara Chikanobu’s Concert of European Music (1889) (fig. 2) and Hashiguchi Goyô’s Woman in Blue Combing Her Hair (1920) (fig. 3)—to exhibit the art form’s longevity and integration into the identity of Japanese art. When focusing on the first work, I will highlight the transition between the Edo and Meiji periods. In contrast, the second will illustrate the embedded influence of Edo prints on Japanese art as it may be inferred from the Revival and Creative Prints of the early 1900s.

Evidently, this exploration will be intricately connected to the concept of political and social "bodies," as Japan’s historical and artistic journey has significantly been influenced by the establishment of the political and societal institutions since they have come to shape its culture through its fostering of the shared identities, values, and interests of its population.[3] This dynamic is particularly evident in Japan's cultural preservation once it sought to assert itself as a hegemonic power on the global stage alongside Western superpowers during the Meiji period.[4] Japan’s uncompromisable use of ukiyo-e throughout its imperial period (1868-1947)[5] exemplifies its cultural success, showcasing how art is not only a means to pursue political motives but also a way to solidify and celebrate its unique national identity.

In tracing the evolution of Japan’s “traditional” identity, I will explore the lifestyle portrayed through the themes and imagery of Edo art to demonstrate the period’s influence on Meiji and Taishō art, that is, its preservation and persistence in Japanese culture. In doing so, I will focus on Utamaro's The Courtesan Hanazuma Reading a Letter, from the series Beauties Compared to Flowers (Bijin hana awase).[6] This ukiyo-e print exemplifies Edo art’s depiction of the period’s conflicting conservative and erotic cultures. Politically, Edo Japan was characterized by its isolationist foreign policies, strictly structured social hierarchy, and traditionalist approach to culture.[7] Artistic representations of this era depicted Japan as tranquil and stable through portrayals of nature, orderly court scenes, and everyday life as seen in the works of the Literati and Kano schools.[8] However, Japan's internal identity was undergoing a complex transformation due to the influence that ukiyo-e, or the "pictures of the floating world," had on Edo society.

The Floating World epitomizes the intersection between the pursuit of luxury and traditional Japanese culture, articulating the use of meticulously carved woodblocks and the gentle hues of inks and pigments on mulberry paper.[9] The "pictures of the floating world" are full-colour woodblock prints that celebrate everyday life and the interests of Edo’s bourgeoisie.6 Ukiyo-e scenes range from the timeless beauty of geishas to the renowned courtesans and kabuki actors of Edo to the bright colours of the city’s seasonal attractions.[10] Masters of the ukiyo-e style include Kitagawa Utamaro and Hokusai, with the latter popularizing the style of ukiyo-e with his well-known work, The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1831) (fig. 4). However, the phenomenon of ukiyo-e provided not only a visual form of escapism into the luxurious and gratifying lifestyle of elite Edoites but also contributed to the cultivation of a dominant Japanese culture characterized by materialism and promiscuity.[11]

During the late seventeenth century, Japan saw the first of two moral crises marked by the surge of shunga: erotic art executed with the technique of ukiyo-e prints. These types of prints typically depicted youthful bodies and often included exaggerated features with an example being Utamaro’s The Courtesan Hanazuma Reading a Letter. The content was affordable and personable, and preferences varied by gender, age and desires, though citizens were generally more interested in flashy entertainment than pornography;[12] still, these prints, just as other ukiyo-e, were considered base by all and were even used to wrap objects and fish.[13] These overtly, and sexual images realized private fantasies and were specifically made for conditions of solitary pleasure,[14] and yet, the rise of shunga was ironically consequential from the policies of the Tokugawa shogunate (1603-1867)[15] such as "alternate attendance," a strategic geographic initiative to isolate the influential elite from potential moral decay by relocating the entertainment district to Yoshiwara.[16] Despite its best efforts, the Tokugawa shogunate seemed to falter in effectively implementing similar policies aimed at managing the socio-sexual dynamics of Edo, or the "city of bachelors,” a nickname given due to the city’s predominantly male population.[17] The Tokugawa shogunate aimed to improve the poor example projected by its elite in their indulgence of the affordable and adulterous shunga; for this hereditary military and feudalistically structured regime strongly emphasized order and discipline, as reflected by its policies and success in the Pax Tokugawa—a long period of peace which lasted until the mid-19th century. In response to the second surge in Kyoto, the eighth Tokugawa shogun implemented the Kyōhō Reforms between 1722 and 1730, which aimed to improve the shogunate's political and social status, partly due to the first surge of shunga; these reforms included economic policies that demanded the end of shunga production, marking the first such restriction.[18] However, and once more, this suppression paradoxically resulted in a boom, with a revival of interest credited to the invention of full-colour printing technology, called nishiki-e. This innovation led to ukiyo-e becoming a luxury art form, becoming increasingly expensive.[19] Although this print genre persisted into the Meiji period, it eventually fell out of favour due to changing societal norms, the emergence of new artistic themes, and national image concerns as Japan sought to engage with global superpowers and become an imperial power.[20] Examining the Edo period's history from a socio-cultural perspective reveals a stark contrast between traditional values and immoral inclinations. These are illustrated in Kitagawa Utamaro's The Courtesan Hanazuma Reading a Letter, a late eighteenth-century coloured woodblock print that presents the intersection of everyday life, “the floating world” and the eroticism of shunga. This ukiyo-e print showcases popular themes of traditional Edo art while also serving as a testament to the tension between the influences and demands of the political and social bodies during the period. Ultimately, this print highlights the interplay between political motives, economic factors, and the sexual culture of Edo under Tokugawa rule, thus contributing to this analysis of the history of Japanese national identity through ukiyo-e.

The subject of this print is the courtesan Hanazuma of the Hyōgoya brothel,[21] whose status and occupation personify both elitist and hedonist aspects of Edo living. The courtesan captivates the viewer with her one-quarter portrait, creating an intimate experience that evokes the sense of being part of the Edo elite. The portrait has declined in quality over time, as seen in the fading ink and purity of the once-pale powdered mica used for the background; yet the courtesan's beauty remains ever enchanting. As the viewer gazes upon her, a mix of caution and desire emerges, reflecting the experience of the citizens who experienced the complex dynamics of the relationship between the policies of the Tokugawa shogunate and the social trends of Edo. The courtesan’s face is defined by delicate black lines, creating a striking contrast against her pale complexion that emphasizes the balance between her long and small facial features. This gives her an air of orderliness amidst the tumultuous life that the “city of bachelors” forces her to lead. Evidently, Hanazuma’s place as the protagonist of this artwork serves as a testament to the dualistic perspectives and identity carried by the people who composed the political and social bodies of the Edo period.

The courtesan is adorned in a check pattern and salmon-coloured kimono whose tone pays homage to the surrounding Japanese wildlife in the Sea of Japan and the Pacific Ocean. The island itself floats around her, a native flower of white and red appears inside a thinly lined circle, and the voices of its people echo throughout the page in thick calligraphy. This portrait asserts Japan's unique identity, both nationally and globally, in the use of its language, fashion, artistic style, and the face of its people.

Yet, in specifically applying the context of ukiyo-e the Edo period, we find the courtesan herself to be an emblem of the complex artistic and social worlds in which she existed. Having chosen Hanazuma as his subject, Utamaro's ukiyo-e portrait demonstrates the duality of Edo civilization: A courtesan must maintain a fine balance between the image of traditional culture and the eroticism which she represents.[22] This is evident in the letter Hanazuma holds, which reads: “I have gained an understanding of your appearance from the brush of Utamaro – that artist who shuns replicating others’ work and style, trusting to his mastery alone. At moments when I want to be with you, I look at it, and feel I am there. [The picture] is so like you that my passions stir.”18 Clearly, the letter highlights the art scene of the Edo period by recognizing Kitagawa Utamaro's skill in the ukiyo-e technique, as he successfully captures a picture of the equally enticing and licentious floating world.

Among other details is the courtesan’s hair; her voluminous hairstyle is styled with a kanzashi, a hair ornament that indicates her rank among other women of pleasure. Her winding hairdo ascends in thickness away from those initial short and flowy hair strands on her scalp. In his meticulous delineation, the artist demonstrates his precise skill and realistic ambition for the otherworldly portrait. It appears that Utamaro, a late eighteenth-century artist, was ahead of his time with this cautious detailing, making his style reminiscent of the Revival Prints (shin hanga), a movement of the early 1900s that was popularized by artists like Watanabe Shozaburo (1885-1962) and Hashiguchi Goyō.[23] Even with over a hundred years in between them, The Courtesan Hanazuma Reading a Letter could be seen as a descendant of the Woman in Blue Combing Her Hair by Goyō (1880–1921), a Taishō period artist who brought the influence of Utamaro into the 20th century.[24] From 1915 to 1920, he created a small collection of prints featuring beautiful women, which, while reminiscent of Utamaro's works, closely resembled Western depictions of women due to his quasi-realist style. Evidently, the distinction between Goyō’s ukiyo-e and traditional Edo period works lies in the introduction and lasting impact of yōga, or "Western-style painting." The Meiji and Taishō periods were characterized by the influence of Western art, as some works by artists like Goyō took some elements as inspiration, while others, such as Kuroda Seiki (1866-1924), adopted the shift from ukiyo-e to yōga, as exemplified by his masterpiece, Wisdom, Impression, Sentiment (1897) (fig. 5). In this way, the influence of the West was vital to the transition from the Edo to the Meiji period, as it sparked the ongoing debate about the distinctions between bijutsu (fine art) and kōgei (craft). From an Edoite perspective, both forms of artistic expression are regarded as equals, while on the other hand, the political and social bodies of the Meiji period, not only initiated this dichotomy to the public perception of art but also deemed bijutsu to be the more valuable form of art.

Another element was the historical and political events that led to the innovation that initiated the transition from Edo to Meiji art. As it will be shown, the reevaluation of specific themes, portraiture, and the very definition of art were all consequential to the beginning of globalization in Japan. The arrival of Commander Matthew C. Perry and his "black ships" in 1853, along with the signing of the Convention of Kanagawa in 1854, marked the opening of Japan's Nagasaki port to international trade.[25] This exposure not only introduced Japan to innovation but also to Western artistic standards. The Japanese government sought to shift its allegiance from China to the West to establish itself as a nation-state amidst Western influence in order to become a global superpower.[26] However, the desire to pivot towards fine art was, in many ways, rooted in the same fears that the Tokugawa shogunate had faced over a century earlier. Concerns about the portrayal of Japanese society as promiscuous—exemplified by shunga works such as Utamaro's The Courtesan Hanazuma Reading a Letter—prompted a quick cultural shift towards art that reflected a more "civilized" image that aligned with Western standards. This change occurred as Japan endeavoured to distance itself from perceptions of primitiveness, this transformation aimed to elevate its status on the global stage.[27] Part of the government’s involvement in the arts sphere consisted of its participation and hosting of contemporary expositions. These events played a crucial role in showcasing and popularizing the nationalistic and artistic achievements of Japan on the world stage. At the same time, the unification of Kyoto, Edo—now Tokyo—and other regions contributed to a more cohesive national identity, blurring regional distinctions and traditional boundaries.[28] Nevertheless, the government carefully navigated the adoption of Western practices in order to preserve a sense of Japanese culture, while partaking in the project of modernization. This is well exemplified by the Ministry of Education’s 1887 establishment of the Technical Arts School (Kobu Bijutsu Gakko) in 1887, which served to form a balance between Western techniques and Japanese craftsmanship.[29] The rapid progress and ambitions that accompanied the Meiji Restoration played a significant role in shaping Japan into the modern nation it is today. This transformation was influenced by the growing influence of the European standards of “fine art” which condemned Japanese techniques such as kōgei,[30] and allowed bijutsu to flourish and develop; therefore changing the trajectory of Japanese art.

In her book, "The Splendour of Modernity: Japanese Arts of the Meiji Era," Rosina Buckland presents an in-depth analysis of the Meiji period’s relationship to Japanese art and highlights the establishment of nihonga, or “Japanese-style painting,” as an effort of the Japanese to assert their identity on the global stage.[31] In relating nihonga to the argument on the dichotomy of art, we must consider the purpose which each historical period assigned to art, as the Japanese mindset towards art also stands out to be in sharp contrast after the transition between both periods. The Edo understandings of "fine art" and "craft," where both art forms were viewed as exclusively creative products that communicate an artist's philosophy from start to finish[32] – an approach that obstructs the potential of art as a nation-building tool. Buckland also discusses how the Meiji era aimed to utilize art for the nation's broader goals of global recognition.[33] This led to initiatives to promote art as an export, preserve traditional art, and establish government support for the arts, including creating the Technical Arts School (Kobu Bijutsu Gakko).[34] Over time, various educational institutions were established that offered students a diverse curriculum that included both nihonga and yōga, as taught by international teachers like Antonio Fontanesi and Ernest Fenollosa.[35] Embracing and creating through this new combination of artistic styles, that is nihonga and yōga, allowed Japanese art to be valued internationally for its aesthetics and proved to be significant in representing the nation's development under Western standards, and its emerging sense of nationalism while advocating for and as itself on the world stage.[36] The Imperial Household Ministry played a crucial role in preserving Japan's cultural heritage, emphasizing the importance of preserving traditional art for future generations.[37] This strategic approach recognized art as a tool for cultural diplomacy, education, and heritage preservation, all of which ultimately promote a deeper understanding of a country's history and cultural identity. In addition, Meiji art played a pivotal role in empowering Japanese citizens to represent their country globally.[38]

This shift in Japan’s national image during the Meiji Restoration is exemplified by Toyohara Chikanobu's Concert of European Music (1889). This work is extremely significant in noting the preservation and elevation of ukiyo-e as an integral part of Japan's cultural identity. The most important change to ukiyo-e has been the transformation of its perspective by the nation. The content and medium of Chikanobu's work symbolizes the historical ascension of ukiyo-e from being a base, and often a licentious art form, to a celebrated expression of Japan's fine art on the world stage. Moreover, it represents its evolution as this triptych of woodblock prints combines elements of ukiyo-e and Western influence in a lively scene. There are elements reminiscent of Utamaro’s work, particularly in the focus on women and traditional attire, yet such elements are Westernized. Japanese musicians play symphony instruments in black suits and Victorian-era gowns with vivid brocade fabric. To address the period’s shifting socio-political ideals, Chikanobu's artwork portrays women in a way opposite to Utamaro's depiction of courtesans as objects of desire. Chikanobu takes a distinct approach by showcasing women as capable and equal to men, highlighting their talents and occupations by placing both genders side-by-side, a strategy which evokes the values put forth by the Japanese Enlightenment. Together, they perform under a golden chandelier, creating an unconventional balance in the room between the scattered musicians and the tightly bound chorus line. Despite the present counter-culture between the homogenous Edo and Westernized Meiji ukiyo-e, the influence of a holistic Japanese culture on Chikanobu endures in the presence of a cherry tree, a symbol of the once isolated island. Chikanobu's Concert of European Music is a colourful testament to the era's dynamic fusion of Western and Japanese influences, positioning him as a figurehead in the realm of Meiji period prints. Through his artistic endeavours, Chikanobu captures the essence of the Enlightenment period in Japan and addresses the challenge of cultural assimilation and identity during this pivotal moment in Japanese history.

In conclusion, ukiyo-e prints from the Edo period significantly contributed to forming a distinct Japanese identity, a legacy that endures today. Contemporary artists like Takashi Murakami (1962-) and Yoshitomo Nara (1959-) draw on these prints, celebrating their thematic depth and unique “flatness.” [39] [40] By recognizing and honouring the essence of “Japanese-ness” inherent in ukiyo-e, they have proven the timelessness of the Edo period and its significant role in shaping Japan’s national identity. Through the portrayal of societal norms, traditions, and the experiences of various social classes, the evolution of ukiyo-e prints illustrates the values, ideals and histories that united and separated the political and social bodies of Japan. The works of Edo-period artists, such as Kitagawa Utamaro, exemplify the duality found within Japan’s identity in works like The Courtesan Hanazuma Reading a Letter which includes both the conservative and erotic elements that marked Edo-period culture. Similarly, the struggle between tradition and modernity, as noted by the shift between the Edo, Meiji and Taishō periods, led to a renewed idea of nihonga, "Japanese-style painting," which furthered the evolution of the Japanese identity; a comparison of ukiyo-e from all three periods illustrates this transformation. Upon examining the history of ukiyo-e, it has become clear that national identities are the product of both political and social interests, that is, ourselves. However, this conclusion raises the question of how national identities will be preserved in our heterogeneous and hyper-globalized world.

Appendix

Figure. 1, Kitagawa, Utamaro, The Courtesan Hanazuma Reading a Letter, Woodblock print; ink and colour on paper with mica, the 1790s, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/56793.

Figure. 2, Toyohara, Chikanobu, Concert of European Music, Triptych of woodblock prints; ink and colour on paper, 1889, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/53314.

Figure. 3, Hashiguchi, Goyô, Woman in Blue Combing Her Hair (Portrait of Kodaira Tomi), colour woodblock print with mica, 1920, Art Institute Chicago, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/60805/woman-combing-her-hair-portrait-of-kodaira-tomi.

Figure. 4, Katsushika, Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa oki nami ura), also known as The Great Wave, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjūrokkei), woodblock print; ink and colour on paper, 1831, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/45434.

Figure. 5, Kuroda, Seiki, Chi Kan Jo (Wisdom, Impression, Sentiment), Oil on canvas, 1897-1900, Kuroda Memorial Hall, National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, Tokyo, Japan, https://www.learner.org/series/art-through-time-a-global-view/converging-cultures/chi-kan-jo-wisdom-impression-sentiment/.

Footnotes

[1] Viewing Japanese Prints, “Viewing Japanese Prints: Tôshûsai Sharaku (東洲齋写楽),” Viewingjapaneseprints.net, 2021, https://www.viewingjapaneseprints.net/texts/ukiyoe/sharaku.html.

[2] Viewing Japanese Prints, “Viewing Japanese Prints: Suzuki Harunobu (鈴木春信),” www.viewingjapaneseprints.net, n.d., https://www.viewingjapaneseprints.net/texts/ukiyoe/harunobu.html.

[3] R.W Miller, “2.2 Collective Self-determination” in International Justice: Philosophical Aspects. Elsevier EBooks, January 1, 2001, 7780–86, https://doi.org/10.1016/b0-08-043076-7/01048-2.

[4] Buckland, Rosina. Splendour of Modernity Japanese Arts of the Meiji Era. S.l.: Reaktion Books, 2024. 15.

[5] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Empire of Japan | Facts, Map, & Emperors | Britannica,” in Encyclopædia Britannica, 2019, https://www.britannica.com/place/Empire-of-Japan.

[6] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Asian Art, “Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style,” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, October 2003.

[7] Christine Guth, Japanese art of the Edo Period (Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1996), 9-11.

[8] Gary Wang, "The Arts + Society of Edo Japan," FAH262, Lecture at Sidney Smith Commons, University of Toronto, September 12, 2024.

[9] The Met, “Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style.”

[10] Wang, "The Arts + Society of Edo Japan."

[11] Timon Screech, Sex and the Floating World (University of Chicago Press, 1999): 55-56.

[12] Screech, 42.

[13] Wang, Gary. "Edo to Meiji in Woodblock Prints + Japonisme."

[14] Screech, 42.

[15] The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, “Tokugawa Period | Definition & Facts,” in Encyclopædia Britannica, December 12, 2018, https://www.britannica.com/event/Tokugawa-period.

[16] Screech, 45.

[17] Screech, 42.

[18] Screech, 46-47.

[19] Screech, 48.

[20] Wang, Gary. "Edo to Meiji in Woodblock Prints + Japonisme."

[21] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, museum label for “Kitagawa Utamaro: ‘The Courtesan Hanazuma Reading a Letter,’ from the Series Beauties Compared to Flowers (Bijin Hana Awase).

[22] The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Asian Art, “Woodblock Prints in the Ukiyo-e Style.” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, October 2003. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ukiy/hd_ukiy.htm.

18 Screech, 22.

[23] Wang, Gary. "Meiji to Taisho: ‘Culture’ + ‘Creativity’" FAH262, Lecture at Sidney Smith Commons, University of Toronto, October 3, 2024.

[24] J. Thomas Rimer et al. Since Meiji: Perspectives on the Japanese Visual Arts, 1868-2000, (University of Hawaii Press, 2017). 369-76.

[25] Hiroyuki Shimatani and Masato Matsushima, Remaking tradition: Modern Art of Japan from the Tokyo National Museum (The Cleveland Museum of Art, 2013), 14.

[26] Buckland, 15, 23.

[27] Shimatani and Matsushima, 15-20.

[28] Buckland, 11.

[29] Rimer et al., 22-25.

[30] Buckland, 19-24.

[31] Buckland, Rosina, Splendour of Modernity: Japanese Arts of the Meiji Era, S.l.: (Reaktion Books, 2024).

[32] Rimer et al, 410-413.

[33] Buckland, Rosina, Splendour of Modernity: Japanese Arts of the Meiji Era, S.l.: (Reaktion Books, 2024).

[34] Rimer et al., 22-25.

[35] Rimer et al., 22-25.

[36] Buckland, 16.

[37] Buckland, 20-28.

[38] Wang, "Intro: World’s Fairs, Nations + Neologisms: ‘Fine Art’ + ‘Craft’ ca. 1873," FAH262, Lecture at Sidney Smith Commons, University of Toronto, September 5, 2024.

[39] Takashi Murakami, Superflat (Tokyo: Madra, 2000).

[40] Wang, Gary. "Modern’ + ‘Contemporary’: ‘Fine Art,’ ‘Anti-Art,’ ‘Non-Art,’ ‘Pop Art’" FAH262, Lecture at Sidney Smith Commons, University of Toronto, November 28, 2024.