Perception and the Body in Vito Acconci’s “Blinks”

Written by Catriona Reid

Edited by Nicholas Raffoul

In her seminal book, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, Lucy R. Lippard defines Conceptual art as “work in which the idea is paramount and the material form is secondary... and/or dematerialized.”[1] During the 1960s, the attention once given to medium, form, and aesthetic appearance in a work became refocused on the idea and processes behind the artwork’s conception. By prioritizing thought over material, Lippard claims the Conceptual artist’s studio reverts back into the study.[2] Sol LeWitt, artist and close friend of Lippard provides another definition of Conceptual art, illuminating the difference between (lowercase) “conceptual” art, which refers to his own work and maintains a focus on materiality while stemming from an original idea and the category of (uppercase) “Conceptual” art, which classifies the work of “anyone who wanted to belong to a movement.”[3] Lippard and LeWitt’s complementary definitions emphasize the importance of the idea in the production of “ultra-conceptual” art.[4]

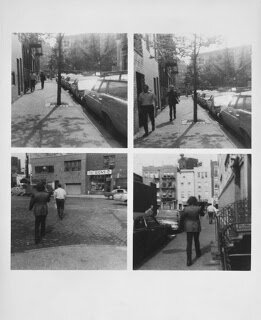

Fig. 1. Vito Acconci, Blinks, afternoon, November 13, 1969, Kodak Instamatic 124, b/w film.

Vito Acconci’s 1969 works are “Conceptual” by Lippard’s definition in the sense that his activities such as Blinks and Following Piece abide by protocols which result in the performance of an idea conceived by the artist alone. These works do not end with the creation of an aesthetic object, rather the artistic goal is the very process of performing these actions. Therefore, although Acconci does not refute Lippard’s definition entirely, he does, however, complicate it through the use of his body in his performances, suggesting a supplementary clause be made to Lippard’s definition to categorize Acconci’s artworks as Conceptual art. Using Lippard’s definition of Conceptual art as a foundation to build from, I will argue that while Acconci’s Blinks emphasizes idea over materiality, the importance of the body and his use of the camera as a “prosthetic,” resulting in a material product pushes against the confines of Lippard’s definition.[5] For Acconci, both the idea in action and the material object are vital.

Blinks [fig. 1] is an activity which took place on a street in New York City in November, 1969. The work is recorded as a collection of twelve black and white “photoworks,” captured using a Kodak Instamatic 124 with black and white film.[6] Acconci recorded his work through note-taking and photography like many of the activities he performed in 1969. The work is presented as a balanced composite layout; the strip of photographs is central and flanked by copies of Acconci’s personal notes which are written on legal pad or using a typewriter. His protocol is as follows: “Holding a camera, aimed away from me and ready to shoot, while walking a continuous line down a city street. Try not to blink. Each time I blink: snap a photo.”[7] Forcing h imself to refrain from blinking as he walks, Acconci produces a series of photographs of what he cannot see while his eyes are closed.

Fig. 1: Vito Acconci, Blinks, afternoon, November 13, 1969, Kodak Instamatic 124, b/w film.

Acconci’s infatuation with the body is evident in his book, Diary of a Body, in which he often employs his body in the performance of lengthy and imposing activities. Not only does Acconci use a camera to document his activities, as many Conceptual artists choose to do, but in Blinksthe camera becomes an extension of his body, resulting in a series of photographs which serve a purpose more complex than mere documentation.

Blinks complicates Lippard’s definition of Conceptual art in the following ways: first, the artist’s body is the singular performing agent — it is Acconci himself who executes the task based on his own need to blink. Therefore, the body becomes just as important as the idea of performing the activity. Second, not only is Acconci’s body a crucial element of the work, but he also utilizes the camera as an extension of his body, allowing him to mimic his sense of vision during the moment his eyes shut. Lastly, the materiality of the work is not subordinate to the conception, but rather a product of it.

Much of Acconci’s oeuvre involves the exploration of his own body. The conception of Blinksis evident in the title: an exploration of the physical act of blinking, the artist asks: what is it to blink? What is eliminated in the process? Though the idea to analyse the act of blinking comes first, blinking is fundamental, if not equal in value, to the idea when producing the work. It might also be argued that Acconci’s body, the site where the act of blinking occurs, exceeds the idea in importance. Acconci’s need to blink becomes the catalyst for the rest of the work. Once he blinks he must click the shutter of his camera, resulting in a photograph of what his eyes fail to capture. Furthermore, the movement forward, produced through the act of walking, results in incremental advancements visible in each of the twelve photographs. Thus, Lippard’s definition acknowledges the importance of the idea in the production of Conceptual art, however Acconci’sBlinks suggests the body is just as crucial in creating such a work of art.

Not all of Acconci’s works exemplify the same bodily awareness as Blinks. Although Following Piece [fig. 2] also involves the fundamental use of the artist’s body, Acconci’s bodily agency fades throughout the artistic process. The work involves the “daily scheme” of stalking strangers through the streets of New York until they enter a private space, such as a home or an office, in which the artist cannot enter.[8] Acconci performed this work over 23 days for varying lengths of time, from a few minutes to several hours. Through his obsessive modus operandi, Acconci questions where to situate his body in relation to public and private space. When discussing this work, Acconci notably claimed, “I am almost not an ‘I’ anymore. I put myself in the service of this scheme.”[9] His surrendering to the compulsiveness of the activity, and the pursuit of others in activities unrelated to his own needs, ultimately results in a dissociation from himself. Though Acconci initiates the self-imposed protocol of following individuals until he no longer can, he concedes to the path of each stranger, allowing his agency to slip away.

Fig. 2: Vito Acconci, Following Piece, from “Street Works”, October 3-29, 1969, activity.

In contrast, the instructions of Blinks are actively obeyed by the artist who must hold his eyes open with force. Pressing the camera shutter while blinking is an unnatural act, as pushing down and blinking must be consciously synchronized. Although the afternoon period during which Blinks was performed is minimal in relation to the 23-day duration of Following Piece, the artist’s agency differs significantly in both works.

While the body is crucial in Blinks, Acconci’s use of the camera as a bodily extension sheds light on an area Lippard’s definition does not. In his brief description of the work, Acconci calls the camera a “prosthetic,” suggesting it serves as a technological extension of his optical capabilities.[10] The presence of the body is acknowledged in the title, Blinks, and in the artist’s conceived idea, but the body is not visible in the twelve documenting photographs. Instead, bodily presence is implied through the camera, acting as the artist’s supplementary method of sight. In his notes, Acconci writes, “...camera as a means to ‘keep seeing’— when I blink I can’t see.”[11] The camera becomes a perceptive tool, elemental not only to the documentation of Acconci’s performance of the work, but as an additional form of human perception. Therefore, the role of camera and the body become equal in importance to the idea of the work.

Illustrating the notion of the dematerialization of art, Lippard claims “If Minimalism formally expressed ‘less is more,’ Conceptual art was about saying more with less.”[12] The movement away from the concrete art object toward the intangible was expressed through the performance of activities. Such Conceptual works were often documented through the mediums of text, video, or photography, which Lippard calls “un-intimidating” media, implying they are conventional and plain.[13] In many Conceptual works documentation through conventional mediums is crucial, providing evidence that the works took place. Though Acconci’s Blinksmay appear to be in accordance with Lippard’s “dematerialization” claim because it minimizes material creation, the photographs and the notes are in fact the productof the work.

Anne Wagner on Following Piecewrites: “Tailing, he is tailed by a photographer, Betsy Jackson...the two recognized parties to the piece become three.”[14] In contrast to the singular active artist/agent in Blinks, Acconci hires another actor to consciously document the processes of Following Piece. Third-person documentation is not present in Blinks. While it is evident Acconci is familiar with the use of documentary methods, he chooses to document Blinks through a first-person perspective.

In Blinks,taking photographs is not a task performed retrospectively or by another documenting assistant. The photographs are taken by Acconci himself, during the process in response to his own blinking. The relationship between the act of blinking and the act of capturing an image assign the photograph a dual significance: as both documentation and final product. Because Acconci’s photographs hold more value than mere proof the activity took place, this work refutes Lippard’s claim that “highly conceptual art...upsets detractors because there is ‘not enough to look at.’”[15] The twelve photographs are crucial visual aids which narrate Acconci’s movements, and offer a diaristic approach which must be studied in order to comprehend the work.

Acconci’s notes provide further evidence of his intention to produce a material product. He writes: “artwork as the result of bodily processes (my blink ‘causes,’ produces, a picture).”[16] The act of pressing the camera shutter defies the act of blinking. Blinking is reductive, inhibits the eye from seeing, obscures perception, and blacks out all images from sight. But for a split second, the shutter of the camera opens while the eye shuts. The protocol of Acconci’s work requires the creation of a tangible product, contradicting Lippard’s claim that Conceptual art moves away from materiality. Blinks simultaneously is and is not a Lippardian Conceptual work. The idea does not supersede the body and the camera, it simply precedes them. The camera facilitates the enactment of the idea, conflating with Acconci’s body. As both his eye and his memory, the camera and the body become intertwined. All three blur together. Acconci complies with Lippard’s notion of prioritizing the idea, but produces a fundamental material object, demanding the expansion of Lippard’s definition of Conceptual art to include the process of production and the elements necessary to create a final material work.

endnotes

[1]Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), vii.

Lucy R. Lippard and John Chandler, “The Dematerialization of Art,” in Art International 12, no. 2 (1968): 46.

[2]Lucy R. Lippard, Six Years, x.

[3]Lucy R. Lippard, Six Years, vii-viii.

[4]Lippard and Chandler, “The Dematerialization of Art,” 46.

[5]Vito Acconci, Sarina Basta, and Garrett Ricciardi, Vito Acconci: Diary of a Body, 1969-1973, (Milano: Charta, 2006), 114.

[6]Kate Linker and Vito Acconci, Vito Acconci (New York: Rizzoli, 1994), 14.

Acconci, Basta, and Ricciardi, Vito Acconci: Diary of a Body, 1969-1973, 114.

[7]Acconci, Basta, and Ricciardi, Vito Acconci: Diary of a Body, 1969-1973, 114.

[8]Anne Wagner, “Performance, Video, and the Rhetoric of Presence,” October 91 (2000): 62.

[9]Linker and Acconci, Vito Acconci, 20.

[10]Acconci, Basta, and Ricciardi, Vito Acconci: Diary of a Body, 1969-1973, 114.

[11]“Blinks (1969),” Vitoacconci.org, accessed November 4, 2018. http://www.vitoacconci.org/portfolio_page/blinks-1969/.

[12]Lippard, Six Years, xiii.

[13]Lippard and Chandler, “The Dematerialization of Art,”46.

Lippard, Six Years, xi.

[14]Wagner, “Performance, Video, and the Rhetoric of Presence,” 63.

[15]Lippard and Chandler, “The Dematerialization of Art,” 46.

[16]Acconci, Basta, and Ricciardi, Vito Acconci: Diary of a Body, 1969-1973, 114.