Early Oligarchal Penology: The Amsterdam Rasphuis as a Built Portrait of the Dutch Republic

Written by Robert Pelletier

Edited by Sam Lirette

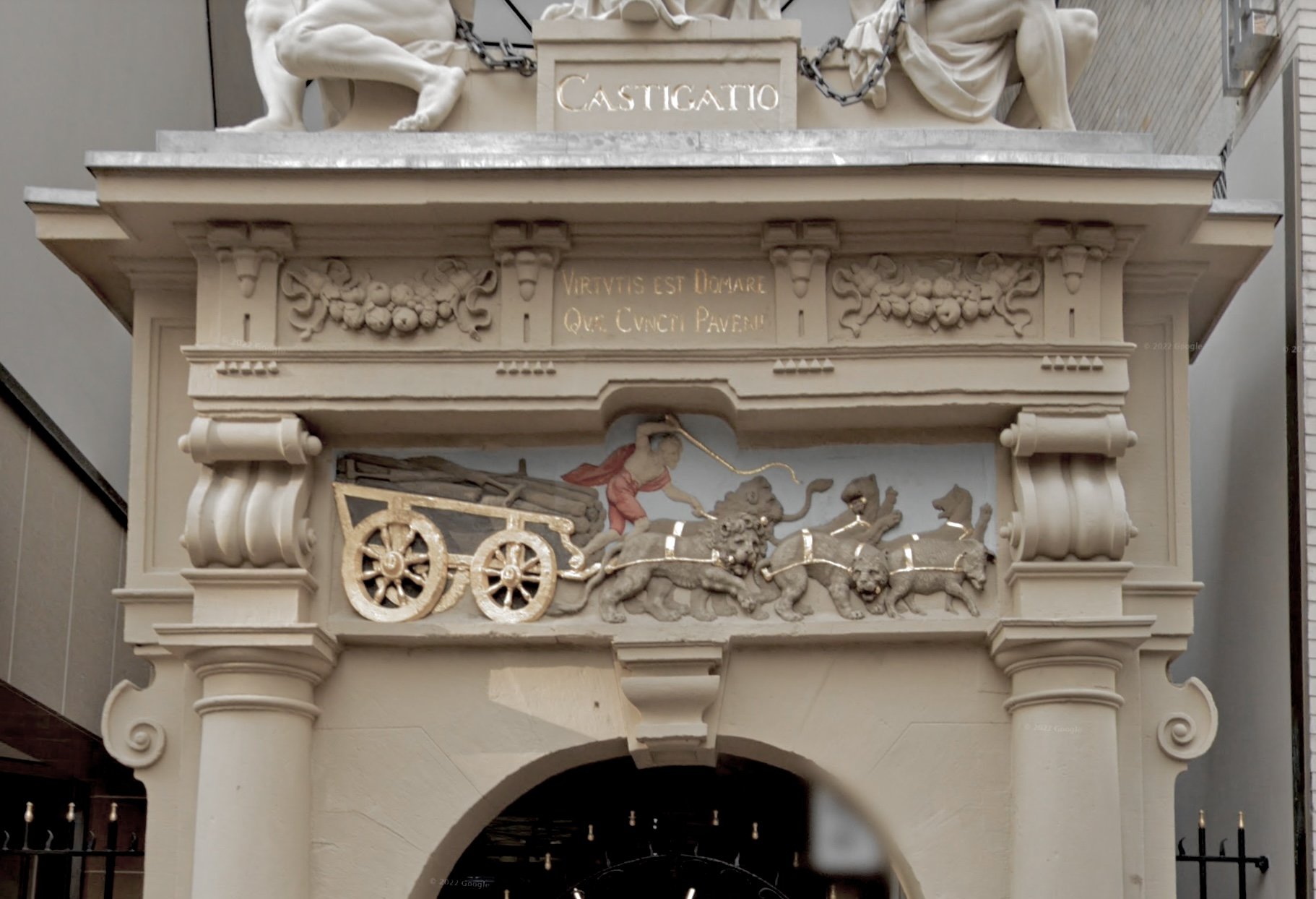

Figure 1. The entrance portal to the Rasphuis (Photograph by the Amsterdam Municipal Department for the Preservation and Restoration of Historic Buildings and Sites, 2008.)

Introduction

One can nearly imagine the vibrant red hue drenching the ground in the courtyard of the Rasphuis, Amsterdam’s criminal reformatory built at the turn of the seventeenth century. Here, men were sentenced to forced labour rasping Brazilwood, which produced a red dye that was sold by the institution to cloth dyers.1 The entrance to the Rasphuis (fig. 1) contrasts sharply with contemporary prison architecture; designed by Hendrick de Keyser in 1604 with additions in 1664, the sumptuous sculptured portal is covered with Mannerist ornamentation, inlaid with a bas-relief narrative, and crowned with three figures whose rendering recalls the work of Michelangelo.2 The portal both welcomes visitors and sends a warning disciplinary message to those who pass under it. Dutch citizens and foreigners who visited this site to witness the punishment of criminals may likely have been surprised by the form of punishment they saw past the portal. Although brutal, the Rasphuis constituted a radical new form of penology, forcing criminals into labour rather than executing them. Executions were a regular part of life in the Dutch Golden Age and functioned to make public examples of law-breakers and visibly manifest the power of the Dutch government.3 This republican form of government was novel in European history and was characterised by its independence from Spain, its Calvinist religion, and its extensive global colonisation efforts which endowed its mercantile citizens with extreme wealth at the cost of countless human lives in the slave trade. This sudden wealth up-ended Dutch culture, inspiring new attitudes towards identity, new functions of art, and new hierarchical conceptions of social order. It is within this context that the Rasphuis was created; functioning as a built portrait of the city, Hendrick de Keyser’s 1604 design of the Amsterdam Rasphuis portal makes salient the opportunity afforded to wealthy Dutch citizens to fashion identity of self and subordinates in the Dutch Republic.

Figure 2. Detail of the Rasphuis Portal. Google Earth Street View, 2023.

A brief formal analysis of the art object at hand will ground further discussions. The Rasphuis was founded in 1595 and its entrance portal was built in 1604. In 1664, a sculptural addition crowned the portal depicting Castigatio, an allegory of punishment.4 From its inception, the portal was symmetrical and adorned with playful manipulations of neoclassical forms. Rounded scroll-like capitals frame a frieze that depicts a man whipping a variety of beasts that pull a cart laden with Brazilwood (fig. 2). Two garlands are shaded by a cornice, under which a quotation from Seneca is engraved: “It is a virtue to subdue those before whom all go in dread.”5 The opening of the portal is roughly 3 metres in height and 2 metres in width, responding to the scale of its context. The keystone and imposts of the arch are rendered with detail while peripheral Mannerist ornamentation protrudes laterally from the portal, forming an ornate silhouette which is extruded only slightly from the wall. A 1783 etching (fig. 3) depicts a four-storey building to the left of the Rasphuis whose facade exemplifies typical domestic Amsterdam architecture with extensive glazing at the ground level and a sumptuously ornamented gable.6 After the closure of the Rasphuis in 1815 and the building’s demolition in 1892, the portal (including its 1664 addition) is all that remains today.

Figure 3. Entrance to the Rasphuis in 1783. (From Marvin E. Wolfgang, Pioneering in Penology: The Amsterdam Houses of Correction in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944), 33.)

Identifying the National Self

Dutch national identity was informed by multiple phenomena, including the conception of identity as malleable, stylistic trends that built off of the Italian Renaissance, and the societal dominance of mercantilism and the hierarchy it entailed. The Dutch were highly concerned with their national identity as a result of their extensive commercial relations throughout Western Europe and their role as a leading cultural centre.7 With the rise of colonialism and mercantile trading came extreme sudden wealth to Dutch traders, whose individual and familial identities were placed in a state of flux. The notion that these wealthy mercantile families were able to fashion their own identities, presentable to the public and to themselves, underlined radical new modes of self-conception that departed from the traditional notion of class as inherent and endowed at birth. A relevant example of this is the design and construction of the Dutch royal palace Huis ten Bosch, which was commissioned by Amalia van Solms, Princess of Orange in 1645 in the context of her powerful husband’s death and her waning political and financial agency. Saskia Beranek has compellingly argued that the design of Huis ten Bosch functioned to create, solidify, and make presentable the social and political identity of Amalia van Solms.8 At Huis ten Bosch, “status and identity were inscribed on a residence”9 to present an identity of nobility independent of aristocratic ancestry.10 Politically useful, the representation of the self extended beyond painted portraiture. This is an important premise for considering the Rasphuis portal as a built portrait of the Dutch Republic; just as a painted portrait can evidence the creation of an individual’s identity, the design of one’s home can serve that same purpose. When that structure is public in function, its design can be considered as a portrait of the society that constructed it.

By drawing upon a visible stylistic connection with Renaissance Italy, the Dutch Republic—like many of the individuals who occupied its wealthier echelons—framed itself within a noble ancestry that justified and solidified its newfound power. This practice of calling back to noble ancestry (fabricated or not) as a means to legitimise new bodies of authority was widespread among newly-wealthy Dutch individuals for whom “lineage and ancient roots caused and justified claims for privileges and superiority.”11 In the case of the Rasphuis, public art is used to a similar effect. The ornamentation of the Rasphuis portal evidences the importance of Italian Renaissance architectural language in the Dutch Republic, particularly following the proliferation of Gothic architecture in the sixteenth century.12 This existing Gothic architecture was widely familiar and “in it, the character of the country had been able to express itself” prior to the Reformation and the Republic’s rapid rise in wealth.13 Because of this, it would be reasonable to infer that Gothic architecture carried connotations of Roman Catholicism and mediaeval Dutch identity which were found to be unsuitable for the new Dutch Republic. A new architectural language that may speak more articulately to the values and life of the modernised Republic was required, and the Dutch found fertile ground in the architecture of their southern neighbours.

Architectural treatises such as Palladio’s I quattro libri dell’architettura (1570) and Scamozzi’s L’idea dell’architettura universal (1615) were central in the development of an architectural idiom suitable for the Dutch Republic.14 Subsequently, reinterpretations of forms from antiquity became common in both domestic and civic architecture.15 Sim Hinman Wan has advanced an argument that the Dutch reproduction of Renaissance Italian forms was more than superficial; rather, it was strategically employed, particularly in philanthropic establishments in Amsterdam (such as the Rasphuis, orphanages, and homes for the elderly16), to establish governmental socio-political power. The deployment of this power in classical architectural forms may be attributed to the emotional effect of this idiom, functioning similarly to Gothic architecture’s role of inducing awe and inspiring religious fervour in its viewers.17 More importantly, these highly visible public interventions—which are framed as philanthropic—monumentalise the wealthy and relegate those deemed unproductive to the hinterlands of the urban landscape.

Grounded in practices of colonialism and capitalism, power in the Dutch Republic was garnered from hierarchical subordination that defined national self-identity and was reflected in art objects such as the Rasphuis portal. Identifications of the national self were informed by the means by which these portraits (built or painted) were made; that is, the capital accrued from colonialist and mercantilist practices and exercised in the commission of these artworks, though unseen, is a constitutive element of the Dutch national self-conception. Dutch involvement in the slave trade played a central role in the accumulation of their wealth, and the relevance of this fact should not be overlooked when considering domestic manifestations of forced labour. This is not to equate or compare the forced labour of the Rasphuis inmates with the forced labour of those enslaved by Dutch traders; rather, the consideration of another realm where power was exerted as a means to a capital profit clarifies an important aspect of national Dutch self-identification in the seventeenth century. This identity could be forged with intention because of the economic and social context Dutch oligarchs had constructed. These men soon realised that they were able to fashion identities not just for themselves, but for others as well.

Imposing Identity on Others

Aside from contributing to national self-identity, various aspects of Dutch Republic life such as engagement in the slave trade, oligarchy, Calvinism, and patriarchy point toward the tendency of the Dutch ruling class to fabricate and impose identities on those they subordinated. This included, among criminals, those whose labour they exploited and those whose existence was perceived as threatening to the power hierarchy that served wealthy Dutch men: women, racialized individuals, and those in poverty. Just as the construction, renovations, and iconoclasm of churches materially defined Amsterdam as Protestant,18 the construction of correctional facilities like the Rasphuis defined Amsterdam as fundamentally hierarchical and evidences the dynamics of class- and gender-based exploitation which grounded this social structure.

Dutch involvement in the slave trade dictated the terms in which domestic criminal reform would be articulated: an economically lucrative means to relegate all people into discrete identities that fit within a predetermined hierarchy under a facade of religious homogeneity. The ideological conception of the Rasphuis constitutes a translation of Dutch slavery practices from their colonial hinterlands to their domestic, symptomatic of a political landscape in which sovereign power is minimised and disciplinary power is exerted to distil the Dutch self-portrait of hierarchy. Direk Coornhert’s 1587 text Boeven-tucht was the first call to replace the death sentence for some criminals with forced labour.19 The impetus for this comes directly from a consideration that “even unskilled slaves cost eighty to a hundred ducats,”20 framing the frequent executions of Dutch criminals within monetary terms to justify the adoption of forced labour of Dutch citizens. This discourse, which allowed for the assignment of a potential value to “a mass of human material completely at the disposal of the administration,”21 is indivisible from the colonial slave trade which produced it. Underlining this justification of forced labour is the motive of religious stability in the form of a unified Calvinist populace. In both the slave trade and domestic correctional facilities, the spread of the state religion was central.22

Behind the Rasphuis gate and on the east side of the inner courtyard was a hall known synonymously as the “church” and the “school,” where inmates attended religious services.23 Inmates' weekly attendance at religious services was mandated, demonstrating the precision with which their everyday life was regulated and a wider trend that characterised the religious didacticism of the Rasphuis.24 Born out of the slave trade, Dutch attitudes toward the malleability of the identities of others are folded into the fundamental ideological conception of the Rasphuis. Canonical analyses of the Rasphuis and its penological novelty (such as Marvin E. Wolfgang’s Pioneering in Penology) stress the humanity of its intentions, considering only superficially the effects of forced labour on reformed criminals.This approach is deeply flawed; not only does it gloss over the nefarious origins of Dutch attitudes towards the malleability of identity (that is, the slave trade), it works within a oligarchical framework that justifies the imposition of identity on those who are subordinated.

Although Direk Coornhert ideologically sparked the institution of Dutch criminal reform, Jan Laurenszoon Spiegel was the city official who proposed a definitive plan for the Rasphuis. In it, he specified “utmost secrecy” for inmates, including a ban on visitors.25 However, by 1608, the Rasphuis began to be a regular exhibit for visiting dignitaries and international ambassadors; later, middle-class visitors to the Rasphuis were not just allowed, but encouraged.26 Admission fees collected from local families and visiting tourists alike provided a substantial source of income for the Rasphuis, where the forced labour of inmates served as a disciplinary warning against crime.27 Punishment at the Rasphuis, then, was framed as a spectacle; its insertion into Dutch life as a lucrative tourist attraction frames the facility as an upholder of the hierarchy’s “othering” of those in poverty. More than any other reason, inmates ended up in the Rasphuis due to begging on the street,28 indicating the desire of Dutch oligarchs to displace the urban poor and make their existence within the public sphere obsolete, save for their capacity to frame the Republic in a positive light to visiting tourists. The role of the Rasphuis may then be reduced simply to “the warehousing of an urban underclass.”29

The female counterpart to the Rasphuis, the Spinhuis, enriches the consideration of Dutch penal systems as institutions where identity is imposed; the Spinhuis combines notions of domesticity and surveillance of womens’ bodies to make salient the patriarchal function of the Dutch Republic in imposing identity. Founded in 1597 under similar ideological motives,30 the Spinhuis housed inmates whose forced labour was the production of textiles as a means to reincorporate subversive women such as sex workers and urban women in poverty31into the Dutch hierarchy. An analysis of the Spinhuis warrants a research paper of its own, but insofar as it is a manifestation of patriarchal enforcement, its inclusion in this paper is critical in that as an institution, the Spinhuis speaks directly to the gendered hierarchy which the Rasphuis only implies. The existence of sex workers, women in poverty, and economically independent women threatened the hierarchy of the Dutch Republic which hinged on the sexual, economic, and social subordination of women to men. In the patriarchal Dutch consciousness, women’s bodies were the object of continuous obsession;32 their bodily autonomy was denied, their existence provoked fears of subversion, and thus their domestication was enforced.

Through its function as a built portrait of the Dutch Republic, the Rasphuis makes tangible a societal hierarchy founded on the uplifting of wealthy white men at the expense of subordinating women and those in poverty in the Dutch Republic. Although I have not attended directly to the experiences of racialized individuals in this context, their subordination feeds into the same systematisation of hierarchy previously discussed. We find that the identities imposed by the Dutch on those deemed “Others” within their society were consistently predetermined within the existing hierarchy that served to benefit those same elites.

Conclusion

Domestic correctional facilities embody national self-representation; the case of the Rasphuis and the Dutch Republic has made clear light of this. Much of my analysis and its emphasis on visual surveillance and discrete hierarchy has pointed towards a consideration of the Rasphuis as a predecessor to Jeremy Bentham’s 1791 Panopticon prison design. Although the Rasphuis fell short of refraining from any direct intervention, it did—at least in its intentions—alter behaviour as well as “induce in the inmate a state of conscious and permanent visibility that assures,” to some degree, the automatic functioning of power.33 As a manifestation of disciplinary power (as opposed to sovereign power), the Rasphuis, like the Panopticon, applies power “continuously and economically,”34 reversing the function of the dungeon and rendering visibility a trap.35 Further consideration of the Rasphuis as a predecessor to the Panopticon may provide fruitful implications regarding the function of penological systems to examine a nation’s self-representation and the social hierarchies embedded within it. Employing a formal architectural language that connects the Dutch Republic to Renaissance Italy, the Rasphuis portal evidences an obsession with national self-representation, the novel malleability of identity, and the need to present noble heritage that pervaded the public Dutch consciousness. After successfully reinventing personal identity in domestic portraiture and erasing the identities of others in their engagements in the slave trade, the Dutch oligarchy intentionally imposed discrete identities onto those whose existence threatened the hierarchy in place. The Rasphuis portal, then, cannot be considered in any terms other than oppressive rather than progressive, damning rather than transcendent.

Endnotes

Otto Kirchheimer, “Mercantilism and the Rise of Imprisonment,” in Punishment and Social Structure (Routledge, 2003), 43.

Sim Hinman Wan, “A Spectral Spectacle: Dutch Mannerist Portals at Amsterdam’s New Philanthropic Sites, 1581–1645,” Early Modern Low Countries 5, no. 2 (2021): 359.

Anuradha Gobin, “Picturing Liminal Spaces and Bodies: Rituals of Punishment and the Limits of Control at the Gallows Field,” RACAR: Revue d’art canadienne / Canadian Art Review 43, no. 1 (2018): 7.

Wan, “A Spectral Spectacle,” 359.

Marvin E. Wolfgang, Pioneering in Penology: The Amsterdam Houses of Correction in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944); Original text: “Virtutis est domare que cuncti paveni.”

Depicted in Wolfgang, Pioneering in Penology, 33.

Jakob Rosenberg, Seymour Slive, and Engelbert H. Ter Kuile, Dutch Art and Architecture: 1600 to 1800. (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1966), 221.

Saskia Beranek, “In Living Memory: Architecture, Gardens, and Identity at Huis ten Bosch,” Women Artists and Patrons in the Netherlands, 1500-1700, ed. Elizabeth Sutton (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 85.

Beranek, “In Living Memory,” 107.

Joanna Woodall, “Sovereign Bodies: the reality of status in seventeenth-century Dutch portraiture,” Portraiture: Facing the Subject (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), 96.

Karl A.E. Enenkel and Konrad A. Ottenheym, The Quest for an Appropriate Past in Literature, Art and Architecture, vol. 60 (Brill, 2019), 7.

Rosenberg, Slive, and Ter Kuile, Dutch Art and Architecture, 221.

Ibid.

Beranek, “In Living Memory,” 96.

Enenkel and Ottenheym, The Quest for an Appropriate Past, 330.

Wan, “A Spectral Spectacle,” 334.

Mia M. Mochizuki, The Netherlandish Image after Iconoclasm, 1566-1672 (Ashgate Publishing, 2008), 29.

Katharine Fremantle, The Baroque Town Hall of Amsterdam (Utrecht: Haentjens Dekker & Gumbert, 1959), 94.

Roger Deacon, “‘A Punishment More Bitter Than Death’: Direk Coornhert’s “Boeven-tucht” and the Rise of Discipline,” Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory 56, no. 118 (March 2009): 82.

Idem, 85.

Kirchheimer, “Mercantilism and the Rise of Imprisonment,” 24.

Idem, 45.

Wolfgang, Pioneering in Penology, 33-34.

Kirchheimer, “Mercantilism and the Rise of Imprisonment,” 45.

Wolfgang, Pioneering in Penology, 28.

Idem, 77.

Ibid.

Deacon, “‘A Punishment More Bitter Than Death,’” 82.

G. Geltner, “A Quiet Transfer: The Disappearing Urban Prison, Amsterdam and Beyond,” in Urban Europe, ed. Virginie Mamadouh and Anne van Wageningen (Amsterdam University Press, 2016), 132.

Martha Moffitt Peacock, “The Amsterdam Spinhuis and the ‘Art’ of Correction,” Crime and Punishment in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age: Mental Historical Investigations of Basic Human Problems and Social Responses, ed. Albrecht Classen and Connie Scarborough (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2012): 459.

Kirchheimer, “Mercantilism and the Rise of Imprisonment,” 43.

Peacock, “The Amsterdam Spinhuis,” 463.

Michel Foucault, “‘Panopticism’ from ‘Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison,’” Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts 2, no. 1 (2008): 6.

Deacon, “A Punishment More Bitter Than Death,” 86.

Foucault, “Panopticism,” 5.

Bibliography

Beranek, Saskia. “In Living Memory: Architecture, Gardens, and Identity at Huis ten Bosch.” In Women Artists and Patrons in the Netherlands, 1500–1700, edited by Elizabeth Sutton, 85–111. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019. muse.jhu.edu/book/67835.

Deacon, Roger. “‘A Punishment More Bitter Than Death’: Direk Coornhert’s “Boeven-tucht” and the Rise of Discipline.” In Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory 56, no. 118 (March 2009): 82–88. jstor.com/stable/41802427.

Enenkel, Karl A.E., and Konrad A. Ottenheym, eds. The Quest for an Appropriate Past in Literature, Art and Architecture. Vol. 60. Brill, 2019. jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvbqs5nk.

Foucault, Michel. “‘Panopticism’ from ‘Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison.’” Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts 2, no. 1 (2008): 1–12. jstor.org/stable/25594995.

Fremantle, Katharine. The Baroque Town Hall of Amsterdam. Utrecht: Haentjens Dekker & Gumbert, 1959.

Geltner, G. “A Quiet Transfer: The Disappearing Urban Prison, Amsterdam and Beyond.” In Urban Europe, edited by Virginie Mamadouh and Anne van Wageningen, 131–38. Amsterdam University Press, 2016. jstor.org/stable/j.ctvcszzrh.19.

Gobin, Anuradha. “Picturing Liminal Spaces and Bodies: Rituals of Punishment and the Limits of Control at the Gallows Field.” In RACAR: Revue d’art canadienne / Canadian Art Review 43, no. 1 (2018): 7–24.

Kirchheimer, Otto. “Mercantilism and the Rise of Imprisonment.” In Punishment and Social Structure, 24–52. Routledge, 2003. doi.org/10.4324/9781315127835.

Mochizuki, Mia M. The Netherlandish Image after Iconoclasm, 1566-1672. Ashgate Publishing, 2008.

Nicolaas, Eveline Sint. “Dutch Colonial Slavery.” In Slavery, 22–56. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2021.

Ottenheym, Konrad A. “Amsterdam 1700: Urban Space and Public Buildings.” In Studies in the History of Art 66 (2005): 118–37. jstor.org/stable/42622380.

Peacock, Martha Moffitt. "The Amsterdam Spinhuis and the “Art” of Correction." In Crime and Punishment in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age: Mental-Historical Investigations of Basic Human Problems and Social Responses, edited by Albrecht Classen and Connie Scarborough, 459-490. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2012. doi.org/10.1515/9783110294583.459.

Rosenberg, Jakob, Seymour Slive, and Engelbert H. ter Kuile. Dutch Art and Architecture: 1600 to 1800. The Pelican History of Art, Z27. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1966.

Wan, Sim Hinman. “A Spectral Spectacle: Dutch Mannerist Portals at Amsterdam’s New Philanthropic Sites, 1581–1645.” Early Modern Low Countries 5, no. 2 (2021): 332–365.

Wolfgang, Marvin E. Pioneering in Penology: The Amsterdam Houses of Correction in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1944. doi.org/10.9783/9781512806397.

Woodall, Joanna. “Sovereign Bodies: the reality of status in seventeenth-century Dutch portraiture.” Portraiture: Facing the Subject, 75–100. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997.