Navigating Practicality and Aesthetics: Byzantine floor coverings challenging our estrangement from late antique material culture

Written by Sophie-Anne Bureau, McGill University

Edited by Beatrice Moritz

Introduction

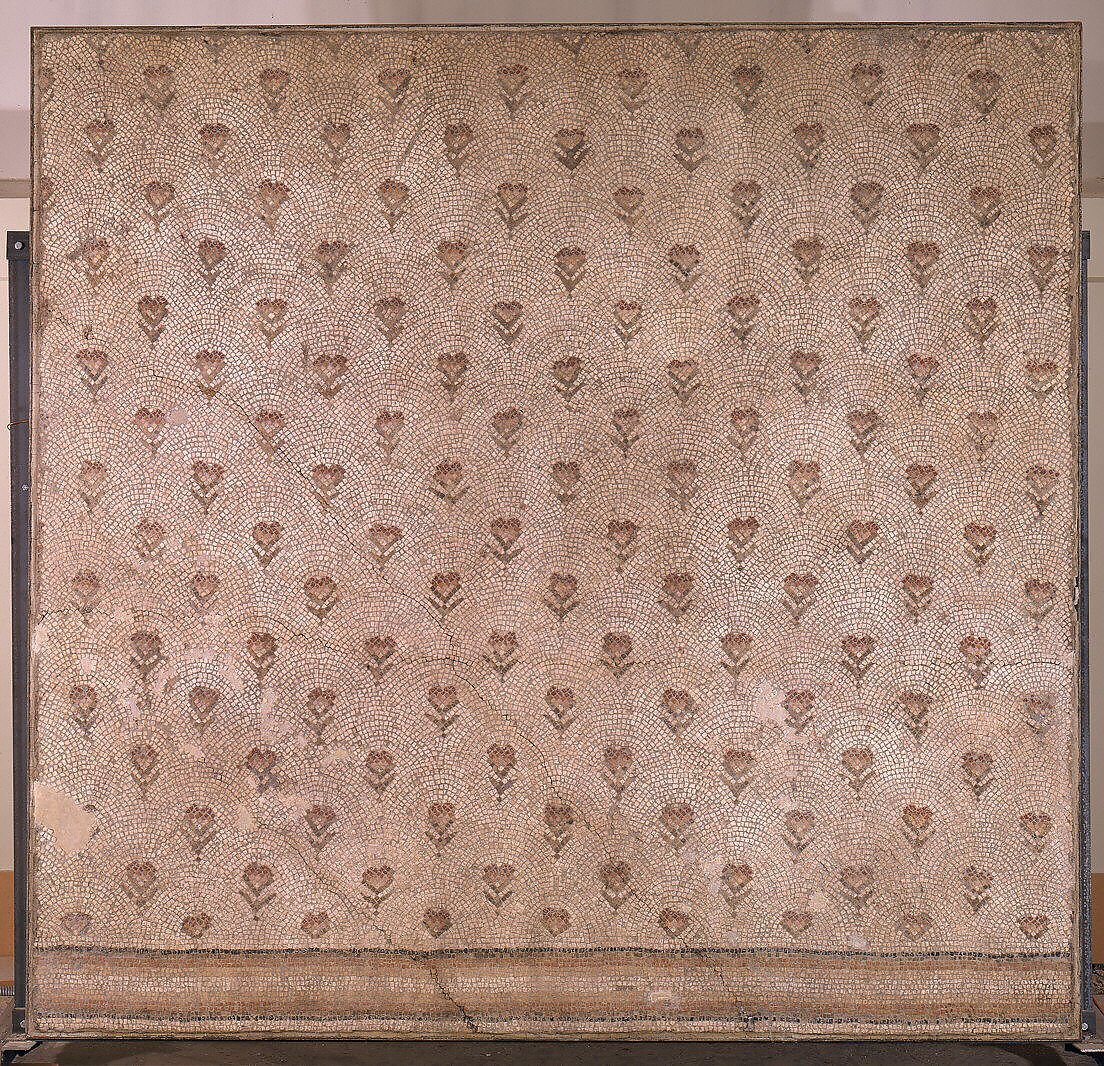

The diverse textile aesthetics seen across Byzantium have continuously been appropriated and reused in modern iterations of rugs often labeled “Persian,” “Oriental,” or even “Turkish.” Nonetheless, rug-making continues to be a significant cultural practice across North Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia.[1] Industrialized processes and global appropriation of designs have disconnected consumers from the makers and the origins of the practice. While the stylistic choices were originally meant to communicate local traditions, mythology, and culture, modern rugs with an “antique look” appeal to mainstream audiences on an often purely visual level. In this essay, I argue that late antique floor coverings relate a timeless and comprehensive artistic language. Textiles are uniquely ephemeral, portable, and permeable, bringing together weaver, owner, and space in a singular piece.[2] The affective, visual, and social powers of floor coverings, a continuously evolving “active” craft and art form, helped to blur the line between function and beauty and, in turn, enhance their longevity and familiarity. Their intersection with other mediums, moreover, further contributed to the popularization and propagation of a secular style. This essay examines the socio-cultural impact of rug-making in the Byzantine Empire through the study of a Carpet Fragment with Mosaic Floor Pattern (c. 4th-5th century) found in Egypt, now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection (fig. 1). Due to the lack of surviving byzantine carpet fragments, the visual analysis of mosaics from the same and later periods will help to fill the gaps caused by limited access to material evidence.

Figure 1. Carpet Fragment with Mosaic Floor Pattern, 4th–5th century, said to be from Egypt, Antinopolis, wool (warp, weft and pile); symmetrically knotted pile, 102 x 117 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Challenges in the Study of Textiles

Since few carpets or rug fragments from Late Antiquity remain, not much scholarship on the subject has been published. Often, the analysis of their visual characteristics and historical significance is the product of speculation and hard to prove hypotheses.[3] Being a functional item used in everyday life, only a handful of examples have survived, and most are unavailable for in-person viewing, or only appear in museum catalogs.[4] Textiles were equally as intricate, luxurious, and historically pervasive as other more traditional and celebrated art forms.[5] The simple fact we do not have many fragments left to support that reality, even less so for floor coverings, contributes to our biased perception of daily life in the Byzantine Empire. While we are most familiar with a perception of the past founded on monumental achievements in architecture, sculpture, or painting still, the more accurate reality of daily life and their frequent interaction with material culture lies dormant.

Considering how difficult ephemeral arts such as textiles are to study, mainstream audiences are understandably more prone to feeling disinterested and indifferent. Since they deteriorate quicker and easier than other mediums, fiber-based works, especially household items such as floor coverings, are often discovered in small fragments leaving their original splendor up to our imagination. Consequently, only highlighting ingenuity and artistry in what remains offers a biased version of Antiquity often focused on a collective, wealthy upper class. To an untrained eye, textile fragments may appear unremarkable, but, in reality, they have an incredibly rich history. Including them is crucial when trying to reconstruct a more factual and relatable version of late antique society.

Additionally, textiles were often recycled and reused, meaning some may have been rugs and carpets but were not explicitly labeled or attached to that function. As such, I found the Egyptian fragment chosen to be the most complete and well-preserved textile specifically labeled as remains of a late antique carpet or rug. Floor coverings are made in a wide range of sizes, materials such as wool, linen, and silk, and techniques depending on the needs and means of the individual.[6] Characteristics such as tassels, motifs and patterns and weaving technique help differentiate floor coverings from other types of textiles but, especially when analyzing fragments from Late Antiquity, classifying based on function and use remains highly speculative and uncertain.

Propagation of Rug Stylistic Conventions Through Secular Motifs and Patterns

Many of the prominent designs, patterns, and motifs seen in Early textiles are joined together in the Carpet Fragment with Mosaic Floor Pattern. This pre-Islamic Egyptian cut-pile rug is made up of multiple rectangular panels, four of which are discernable in the remaining piece, arranged symmetrically on a lattice background, and surrounded by a wide double border. Every panel has a unique central geometric motif with a prominent border filled with a pattern that, again, differs for each. The inner border constraining the lattice pattern and surrounding the rectangular panels has a meandering, labyrinthic design that alternates with equally distanced rectangular pockets filled with more distinct geometric forms. Unlike the rest of the fragment, the outer border has vegetal elements, suspected to be leaves and bunches of grapes. This design breaks the otherwise entirely geometrical composition.[7] Still, the peripheral border has a similar symmetrical, repetitive composition. The work communicates a profound concern for symmetry and geometry in the spatial configuration but not necessarily in its content. Despite being exceptionally busy, complex, and intricate, the fragment presents comprehensive and familiar stylistic, conceptual, and organizational choices.

Figure 2.Two-Faced Carpet Fragment, 1100s, possibly Iranian, senna knot, 39.3 x 16.2 cm, The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Without knowledge of antique textiles and historical context, one could easily believe the MET fragment to be a modern take on an antique style and craft. Recent scholarship states that animal, vegetal, geometrical, and “human” patterns dominated textiles from the 4th and 5th centuries, thus blending Hellenist and Coptic influences.[8] Geometric forms, flora, and fauna have been consistent and significant sources of inspiration for late antique weavers and for centuries after. Over the centuries, Coptic art gradually influenced the transition from realist depictions to more stylized renditions, which in turn heightened the role played by color schemes.[9] If we dissect the fragment further, the various elements weaved in one overarching composition point to this transitional period where such influences from the West started to disrupt the Hellenistic realism style prominent at the time.[10] The inventive, diverse use of colors promoting contrast and visual interest over accuracy, and the inclusion of floral patterns, in this case represented by the vine, are characteristics most notably associated with Coptic art and Early Christian visual traditions.[11] In the 5th-century carpet fragment, the weaver used an incredibly extensive color scheme, including varying shades of orange, blue, pink, and yellow, among others, and blended geometrical and naturalistic elements.

Figure 3. Section of a Marble Mosaic Bathhouse Floor, 537-538, Byzantine marble mosaic, 274.3 x 264.2 cm, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In this transitional period, the style chosen evolved, but the source material remained similar. As such, the fragment’s relatability rests on our ability to recognize the similarities in artistic intentions and the visual language vehiculated, not necessarily the style of representation. A Two-Faced Carpet Fragment from around the 12th century makes this kindred desire to represent nature evident while choosing a style more appropriate for the period (fig. 2). Indeed, the symmetrical and likely repeated motif underscores the geometrical components of perhaps a flower or a tree rather than attempting to create a realistic portrait. The light blue background further defines the different shapes of the white floral motif punctuated by a few small dark dots in the leaves and center. Unlike the MET fragment, this work has a simple, plain, and high-contrast color scheme, making the composition appear flat. This later carpet fragment recalls a 5th-century Byzantine Section of a Marble Mosaic Bathhouse Floor (fig. 3). They have much fewer details than previous examples but still use repetition and symmetrical floral motifs despite representing different art forms from distinct periods and styles.

Understandably, this concern for secularism is not uncommon in decorative textiles with a prominent functional purpose. The stress endured by repetitive stepping, paired with the fragility of fiber, meant rugs and carpets would have been ill-suited for religious imagery. Indeed, in a Roman Christian context, it would not have been appropriate to depict detailed scenes from scripture or human figures on such an easily degradable form of floor decoration.[12] The location and placement of decorative objects heavily determined the composition of the work. As such, a similar mindset constrained floor mosaics’ content to mostly floral, geometric, and mythological motifs during this period.[13] Contrary to textiles’ ephemeral nature, mosaics’ durability and resilience to prolonged strain made it much more appropriate for public spaces such as churches, bathhouses, and halls, while rugs and carpets appeared in places with less foot traffic.[14] The overlaps in the content depicted in mosaics and rugs show the popularity of secular imagery across mediums, and the distinct qualities of the materials used in their creation allowed for its propagation in both private and public spheres.

Figure 4. Detail of Mosaic Pavement, Roman, 2nd-3rd century A.-D., previously at the Lateran Museum, Rome.

Just as cross-cultural mixing and political turmoil had a social, cultural, and economic impact on the fabric of society, taste and style also evolved. While prevalent in Egypt, Hellenism and Coptic Art in textile practices translated in many other geographical areas partaking in textile crafts and various branches of visual culture during the 3rd and 4th centuries.[15]As demonstrated by the 12th-century fragment, some influences maintain their relevance while allowing for stylistic evolution. Being a product of a changing political, religious, and artistic backdrop does not necessarily mean the work communicated a particular ideological message. Despite its religious tone, the Coptic or Early Christian label refers to the historical period when Christianity became increasingly prominent rather than implying any direct association with the Church or God.[16]Early Christian art often opted for depictions of flora and fauna, overstated colors, motifs and patterns, and elements of mythology to convey the desired message.[17]Moving away from overt symbols of religious or political affiliations by focusing on secular designs such as geometry, floral motifs, and stylized patterns increased floor coverings such as ours’ accessibility.

Creative Cross-Contamination Between Floor Decoration Mediums

Figure 5. Mosaic Floor with Running “Carpet” Pattern, 8th century, Khirbat al-Mafjar, Jordan Valley, near Jericho, Hisham’s Palace. Image credit: Ḥ. Tāhā and D. Whitcomb (Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2015).

The overpowering presence of textiles across all aspects of visual culture and the influence shared between different artistic pathways demonstrate the immeasurable impact of creative cross-contamination. The mutual influence between floor coverings and mosaics nurtured the creation of a wide range of motifs, designs, and patterns, some of which we still weave today. Looking back at the 4th-5th century Egyptian carpet fragment, scholar M.S Dimand noticed how much mosaics and floor coverings intersected in his 1930s analysis of the piece. Most notably, Dimand established a direct link between the carpet fragment and earlier and same-century Coptic floor mosaics. The strongest resemblance rests in a 2nd or 3rd-century Roman mosaic that shares an almost identical configuration and a similar blend of geometrical and flora and fauna decorative elements (fig. 4). Furthermore, the shading technique and intentional color juxtaposition in the carpet fragment does suggest a clear desire to imitate the look of mosaics.[18]The mosaic’s influence on the Egyptian rug fragment is undeniable, but the reverse seems accurate as well. Dimand established a unidirectional connection between mosaics to floor coverings but failed to explore how the inverse could be true. Indeed, the backdrop on which the square panels appear reminds us of braid-like interlacing threads or weaving. This mosaic style seems heavily influenced by the act of weaving while also serving as inspiration for later carpet production.

Figure 6. Floor Mosaic from Dīwān, 8th century, Khirbat al-Mafjar, Jordan Valley, near Jericho. Image credit: Harvard Fine Arts Library, Digital Images and Slides Collection (1997), 14642.

In her 2019 article “A Taste for Textiles: Designing Umayyad and Early ʿAbbāsid Interiors,” Williams explicitly links textile visual language and conventions with mosaics. Beyond their explicit association with textiles, they specifically use elements associated with floor coverings as their source material. The 8th-century Mosaic Floor, with a Running “Carpet” Pattern from the Khirbat al-Mafjar, has a repetitive and geometric intertwined roundel pattern contained by a border, in this case, thin and white with a dark outline (fig. 5). This design goes the entire length of the corridor like a shape of carpet known as a “runner.” The colorful chevron pattern on the left and the similar lattice pattern on the right reminds us of the 4th-5th century fragment. Additionally, a Floor Mosaic from Dīwān from the same place and period as the previous mosaic references rugs and carpets through the addition of a twisted border and fringe detailing (fig. 6). Tassels or fringes appear in many forms of textiles, yet the way they border the entire perimeter of the scene makes the association to floor coverings even more convincing.[19] Here, the connection between both art forms goes beyond temporal limitations and demonstrates how the style and form of floor coverings are replicated in mosaics of later periods.

Figure 7. Excavation Photo of a 5th-Century Floor Mosaic with Trellis Pattern from Antioch, 1938, Syria, 515.6 × 261.6 cm. Image credit: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Byzantine Collection, Washington, DC.

While establishing a textile’s inspiration timeline can be incredibly useful when creating a portrait of the artistic practice of a specific period, understanding how inspiration across artistic mediums intersected and were perpetuated over time may be more helpful in our case. The mutual influence between floor coverings and mosaics nurtured the creation of a wide range of works that passed on textile conventions. The impact of floor coverings is notable in many examples from the same time frame as the Egyptian carpet fragment. We can establish clear links to mosaics throughout the Byzantine Empire in terms of the styles and patterns replicated. As seen in an Excavation Photo of a 5th-Century Floor Mosaic with Trellis Pattern from Antioch, Syria, we have a repeated lattice patterned rectangle with each lozenge containing a central clover-like design (fig. 7). The central rectangular shape is bordered by a meandering, reminiscent of a Greek key pattern, band on the width side, and a trellis pattern band on the length. While we do not have the complete mosaic, the intact section shares the same concern for repeated geometric and floral designs with distinct borders. The overall rectangular shape and chosen style hint toward well-known rugs and carpets vernacular. The parallels between both art forms demonstrate they followed similar guidelines regarding composition and form. The mutual influence between mosaics and carpets happened simultaneously and across borders. As a result, we can achieve greater recognition of the creative process and artistic approach of artisans of the past, as well as establish a sense of continuity in the ways we continue to practice and display fiber arts.

Floor Coverings as Architectural Aids

As an architectural aid, textiles served a purpose that other features such as mosaics and carvings could not duplicate. Textiles associated with interior décor, such as curtains, furniture, and floor coverings, operated in ways similar to clothes on a body.[20] Aside from their visual appeal, rugs have an inherent softness, thus providing comfort and support, while breaking the coldness and harshness of a textile-less room.[21] As previously explored, decorative arts such as mosaics and floor coverings communicate the desire to incorporate an intense and complex visual experience without sacrificing function.[22] Above all, their primary role as a practical item meant their use and presence in households transcended most social, cultural, and economic boundaries. Despite having few examples from that era, their overwhelming presence has translated into our present decorative habits. Today, the art of mosaics making, or textiles like tapestries, has mostly been categorized as antiquated practices, thus creating a barrier that differentiates ancient from modern material culture. Rugs and carpets challenge this tendency to undervalue and distance us from previously significant art forms. Indeed, they have stayed a leading force in the floor ornamentation market and continue to be an accessible way to assess how much attention was put into enhancing a room. In other words, they connect us through firsthand knowledge and shared understanding of their contribution to our multifunctional and aesthetic needs. Their capacity to be portable, malleable, and gain sentimental value with time amplifies the closeness between owner and object, thus illustrating the grounds for timeless relevance over other antique decorative tools.

Understanding the various properties of floor coverings also gives us additional context as to their limitations. Since fibers are vulnerable to the elements, floor coverings would have been more practical in interior settings and places where foot traffic may be less concentrated. Mosaics and other representations of textiles in various art forms can help us visualize how floor coverings may have been used. The different references to textiles in the 8th-century mosaics from Khirbat al-Mafjar provided a tangible and almost tactile quality to the space were perhaps an attempt to replicate the warmth and familiarity associated with fabric.[23]As with most textiles produced in Egypt during the late antique period, the MET carpet fragment is made of wool. Egypt was an epicenter for textile production during this period thus, many of the textiles found today come from various regions of its territory.[24]Wool became much more prevalent in Egypt during the Byzantine and Islamic periods since animal fibers were previously considered impure.[25] This material can retain moisture and humidity while staying warm and providing thermal insulation.[26] In floor coverings, wool is versatile, adaptable, and durable and can help transform a space visually and with the ambiance it creates. As such, further than providing beauty and visual interest, the rug was most likely displayed in places that were much more private. Existing in such proximity to their owners and presented in spaces reserved for members of their close circle meant rugs had an additional and significant sentimental value.

Figure 8. Reconstruction of the “Carpet Fragment with Mosaic Floor Pattern,” drawn by Lindsay Hall.

As everyday objects, textiles and floor coverings are incredibly effective in communicating the social, cultural, and economic implications of their fabrication and use.[27] Going back to our 4th–5th century Carpet Fragment with Mosaic Floor Pattern, safe to say it was not intended to go unnoticed once displayed. Apart from the intricate design chosen for the carpet fragment, the preservation and size of the fragment suggest it was an expensive and substantial piece. Some researchers believe the original completed piece was around 6 feet 7 inches long and 4 feet 3 inches wide (fig. 8).[28] Furthermore, threads were dyed using a wide range of rich pigments from all over the Middle East and North Africa.[29] The knotted pile technique required more labor and resources but allowed for more creative and artistic freedom.[30] Grasping the technical implications behind such a fragment gives us a chance to piece together the past while allowing for the conservation of heritage and ancient practices.[31] This work was deliberately loud and large, thus showing off the craftsmanship behind the work, the wealth of the patron, and the various trends of the period. Modern audiences can grasp the sense of pride and sensory delight the carpet fragment brought to those involved in producing such a substantial piece. This fragment represents upper-class consumerism, thus overshadowing the humble reality lived by most during Late Antiquity. Therefore, redirecting our focus towards the inner workings of the production process and the agents involved provides context and helps us more accurately interpret and understand the past.

As a type of floor embellishment, antique mosaics help us reconstruct more accurately how and where floor coverings were displayed and used. Both 8th-century mosaics explored previously came from a bathhouse, heavily frequented, secular places of gatherings. The different methods used to communicate visual interest and how they drape the ground could have helped divide space and guide movement.[32] The addition of “runner” rugs, as suggested by the mosaics’ imitation, helped to give a sense of direction and accompanied individuals along their journey. As a result, including elements of textile conventions in their designs perhaps brought the home to public spaces. Even in spaces where it was impractical to incorporate textiles, floor coverings were still included in the artistic vision and benefitted the overall effect desired.

Conclusion

Art overpowered ancient civilizations’ interiors, and textiles were a prominent part of the embellishment process.[33] The Carpet Fragment with Mosaic Floor Pattern communicates how late antique weavers navigated stylistic conventions and, as such, the social, cultural, and political context. From Hellenist realism to Coptic and Early Christian influences, we encounter secular visual language and textile conventions that persisted throughout time. The clear link between floor coverings and other art forms, such as mosaics, demonstrates their capacity to propagate style and aesthetics across mediums, time, and space. They are relatable visually and in their function, thus making them a great educational tool to bring forward the agency of ancient craftspeople and artists. Incorporating textile conventions in mosaic designs demonstrates how they navigated the constraints of fibers. As such, mosaics adopted many of their visual properties and styles while compromising on the tactile and soft qualities of floor coverings. This dialogue further supports how pervasive and central textiles and rug conventions were in late antique visual culture. Highlighting the parallels and continuity of floor covering helps break misconceptions surrounding these art forms and crafts as exclusively related to the past and detached from their original context and cultural significance. Additional, more focused explorations of the economic, cross-cultural, and technical implications of floor coverings, among other textiles, will undoubtedly contribute to highlighting their agency in past civilizations, thus providing a greater understanding of their contribution to late antique society and material culture at large.

Endnotes

[1] Denny, Walter B. How to Read Islamic Carpets ( The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014), 9-10.

[2] Hoffman, Eva. “Pathways of Portability: Islamic and Christian Interchange from the Tenth to the Twelfth Century,” Art History 24, no. 1 (2001): 42.

[3] Geijer, Agnes. “Some Thoughts on the Problems of Early Oriental Carpets.” Ars Orientalis 5 (1963): 87.

[4] Woodfin, Warren T., “Textile Media.” In The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Art and Architecture, ed. Ellen C. Schwartz (Oxford Handbooks, 2022), 594.

[5] Golombek, Lisa. “The Draped Universe of Islam.” In Content and Context of Visual Arts in Islam, ed. Priscilla P. Soucek (College Art Association of America and Pennsylvania State University Press, 1988), 25.

[6] Denny, How to Read Islamic Carpets, 10.

[7] Dimand, “An Early Cut-Pile Rug,” 152, 157.

[8] Mohamed, Huda. "History of the Textile Industry in Egypt." In Preservation and Restoration Techniques for Ancient Egyptian Textiles, ed. Harby E. Ahmed and Abdulnaser Abdulrahman Al-Zahrani, (IGI Global, 2023), 8.

[9] Dimand, M. S. “An Early Cut-Pile Rug from Egypt.” Metropolitan Museum Studies 4, no. 2, (1933): 159.

[10] Dimand, “An Early Cut-Pile Rug,” 158-59.

[11] Mohamed, “History of the Textile Industry,” 8.

[12] Talgam, Rina, “Christian Floor Mosaics: Modes of Study and Potential Meanings,” In The Routledge Handbook of Early Christian Art, ed. Robin Margaret Jensen (Routledge Handbooks, 2018), 111.

[13] Talgam, “Christian Floor Mosaics,” 107.

[14] Talgam, “Christian Floor Mosaics,” 104.

[15] Dimand, “An Early Cut-Pile Rug,” 158.

[16] Landry, Wendy, Anne-Laure Rameau & Abigaëlle Richard, The Coptic Textiles (Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Collection of Mediterranean Antiquities, Vol. 4, 2020), 3.

[17] Brown, Michelle P. Christian Art, (Lion Hudson, 2021), 44.

[18] Dimand, “An Early Cut-Pile Rug,” 155.

[19] Williams, Elizabeth Dospěl. “A Taste for Textiles: Designing Umayyad and Early ʿAbbāsid Interiors.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 73 (2019): 427.

[20] Williams, “A Taste for Textiles,” 424.

[21] Colburn, Kathrin. “Loops, Tabs, and Reinforced Edges: Evidence for Textiles as Architectural Elements.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 73, (2019): 187.

[22] Van Loan, Theodore. “Textiles by other means: Seeing and Conceptualizing Textile Representations in Early Islamic Architecture.” In Textile in Architecture: From the Middle Ages to Modernism (1st ed.), eds. Didem Ekici, Patricia Blessing, and Basile Baudez (Routledge, 2023), 128.

[23] Van Loan, “Textiles by Other Means,” 133.

[24] Mohamed, “History of the Textile Industry,” 1.

[25] Mohamed, “History of the Textile Industry,” 3.

[26] Ahmed, Harby E. "Fibers and Natural Dyes Used in the Textile Industry During the Historical Egyptian Eras." In Preservation and Restoration Techniques for Ancient Egyptian Textiles, eds. Harby E. Ahmed and Abdulnaser Abdulrahman Al-Zahrani, (IGI Global, 2023), 31.

[27] Landry, The Coptic Textiles, 3-4.

[28] Dimand, “An Early Cut-Pile Rug,” 152.

[29] Ahmed, “Fibers and Natural Dyes,” 37-40.

[30] Denny, How to Read Islamic Carpets, 23.

[31] Tawheed, Hisham Hassan. "Recording and Documentation of Historical Textiles and Their Role in Conservation and Sustainability Processes." In Preservation and Restoration Techniques for Ancient Egyptian Textiles, eds. Harby E. Ahmed and Abdulnaser Abdulrahman Al-Zahrani, (IGI Global, USA, Pennsylvania, 2023), 120.

[32] Williams, “A Taste For Textiles,” 427.

[33] Golombek, “The Draped Universe of Islam,” 26.