Is This What You Want to See?: New Visibility Strategies in Post-Soviet Queer Art

Written by Thierry Jasmin

Edited by Alena Russell

In a 2014 interview, Vladimir Putin announced that Russia must cleanse itself of gay people (1). Similarly, in the past two years, Poland’s government and religious leaders have qualified numerous municipalities as “LGBT-free” zones, supporting right-wing publishers who distributed stickers with the slogan in 2019 (2). Since queer people living in these countries have been rendered invisible, visibility is of great importance for them: “unlike the Soviet period, [...] in post-Soviet Russia the problem of homosexuality is one of visibility” (3). Indeed, after the fall of communism, new visibility did not translate into political agency for the gays, who were often associated with foreign influence and spreading their “disease” (4). This essay explores how contemporary artists in Russia and Poland are currently trying to reclaim the problem of visibility through subversive strategies. It suggests that post-Soviet queer artists are not only trying to make themselves visible, they are embodying the homophobic rhetoric that made visibility impossible in the first place. Indeed, they embrace their culture and queerness simultaneously, undermining the "Western threat" etiquette that was given to their sexuality.

To begin, Russian artist Angel Ulyanov’s Let’s Stir Things Up (2019) (fig. 1) is a bold music video that shines light on the performative nature of masculinity and Russianness. Indeed, the main character is dressed in stereotypical gopnik clothing, typically associated with working-class delinquents, and is accompanied by a group of masculine men. Surprisingly, he confronts a man dressed in bright green and red, but a homophobic attack does not occur. Instead, the protagonist starts voguing, a dance style with roots in the 1960s Harlem ballroom scene, so intensely that he starts bleeding and faints. At the end of the video, he resuscitates covered in glitter as the people around him die. This shift from stereotypically masculine to more feminine and “deadly” movements in the video demonstrates how gay men might pass as straight, highlighting a post-Soviet anxiety about threats to national masculinity. Since the 1990s, LGBTQ+ people have been targeted in Russia as symptoms of a “crisis of masculinity,” because they were seen as embodying the soul of the “opposite sex” (5). In many post-Soviet states, being the breadwinner of the family is a primary characteristic of masculinity, a gender norm seen as undermined by the economy of the post-communist era (6). After the collapse of the USSR, fertility rates had plummeted. Thereafter, the norm needed to be reinforced, and the lines between the masculine and its enemies were constructed to avoid de-masculinization and assure a rise in fertility rates (7). By blurring the lines between masculinity and queerness, the video successfully makes the contradictions of queer erasure evident. Moreover, the erasure of homosexuality in Russia makes for a performative aspect of Russian identity that rejects Western notions of individuality (8). Thus, the video subverts the idea that queer visibility is somehow criminal and not Russian, calling for a political movement that is unique to Russia: as Ulyanov explains, “we didn’t have Stonewall, we have no Pride—but in these circumstances something new, political, and fierce is born” (9).

Figure 1: Ulyanov, Angel. Давай замутим (Let’s Stir Things Up), 2019, performance video, 2 minutes 53 seconds, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NetBsW8hIok.

Similarly, Victoria Guyvik’s photograph (2020) (fig. 2) illustrates how contemporary post-Soviet artists have not only merged traditional culture and queerness, but have in fact embodied the “Western ideology” label that attaches egotistical, materialistic and vulgar sentiments to their sexual orientation (10). Capturing an instant of queer love, the two lovers in Guyvik’s photograph do not seem engaged in their surroundings. By positioning two women freely kissing in front of the two towers of Saint Basil’s Cathedral, a quintessential symbol of Russian culture, Guyvik juxtaposes them and subverts the expected invisibility of LGBTQ+ people. Part of a series of works by Russian Queer Revolution, a platform for the promotion of LGBTQ+ art founded by Anastasia Fedorava, the photograph counters Russia’s “gay propaganda law” put in place in 2013 (11). Like Ulyanov’s video, it makes the bold claim that queerness can exist in public post-Soviet spaces, making fun of the sexual contract that came with the decriminalization of homosexuality, a law contingent on the fact that homosexuals would remain out of public view (12). Moreover, both are wearing multicolour balaclavas, highlighting the associations between queer people and criminality. The photograph plays with the idea that homosexuals are a hidden threat capable of disguising themselves as straight and committing crimes, a distortion vehiculated through the post-Soviet tabloid press (13). It challenges the viewer’s assumptions about queerness by showing that LGBTQ+ people can ironically embody how their country sees them, not really committing crime but merely expressing love for each other. Unrepresented in the West, the photograph shows that queer Russians are not only suffering, but that there is also beauty, joy, pleasure, pride, creativity and talent in being queer in Russia (14).

Figure 2: Guyvik, Victoria. Untitled, Russian Queer Revolution installation, 2020, photograph, unknown dimensions, https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/gallery/28983/7/russian-queer-revolution-installation-2020.

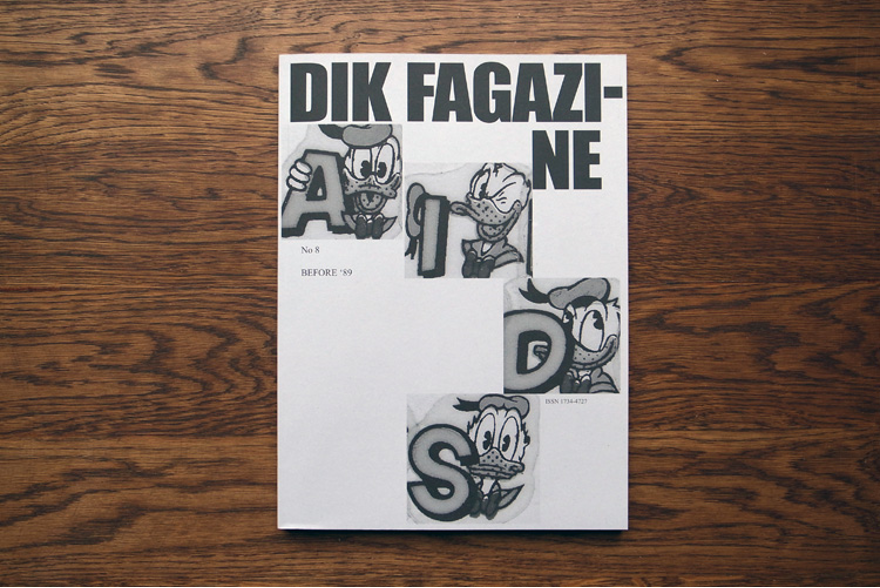

Links between Western society and post-Soviet queerness can also be seen in the eighth issue of Karol Radziszewski’s DIK Fagazine (2011) (fig. 3). It was once shown alongside Filo magazine (1990) (fig. 4), which was founded by Ryszard Kisiel in reaction to Operation Hyacinth, a secret registration of 11,000 queer people from 1985 to 1987 (15). Filo’s founder, Ryszard Kisiel, was inspired by Western magazines as well as the Stonewall Riots, which “were granted the strongest symbolic power in [...] magazines” (16). DIK Fagazine, however, takes queer visibility and its link to Western threats to another level with its vulgar title and the graphic typography spelling of “AIDS” on its front page. The zine’s queerness, vulgarity, and irony are characteristic of Radziszewski’s style. The magazine was founded by the artist in 2005 and particularly focuses on masculinity. The AIDS cover is a direct reference to the wallpaper by Canadian art collective General Idea, but Radziszewski renders the serious topic ironic by depicting Donald Duck affected by the disease. À la Robert Mapplethorpe, the inside of the magazine features nude men in black and white, criticizing post-Soviet sexual taboos. As shown in the previously mentioned music video, links between queerness and death are emphasized. This is not what the Polish public wants to see, but paradoxically, Radziszewski exclusively depicts and subverts ideas that the state itself has spread about homosexuality. He not only investigates the present condition of queer people in Poland, but also establishes the medium of the magazine as something that has been an important part of queer subcultures throughout history. By founding the Queer Archives Institute in 2015 and including archival material in his zine, the artist is voluntarily rewriting the past: “everything that contemporary queer artists are doing is becoming a queer archive in the same way. [...] The history of queer Central Eastern Europe is so undeveloped, so hidden. You have to introduce it with a lot of context, which is a challenge” (17).

Figure 3: Radziszewski, Karol. DIK Fagazine Issue No 8, 2011, magazine, unknown dimensions, http://www.karolradziszewski.com/index.php?/projects/dik-fagazine/.

To better understand how Radziszewski’s strategy is new, it is interesting to further compare it to Filo magazine, which remained underground from 1986 to 1990. It was important in queer life, as its content was triggered by Operation Hyacinth: “especially because the operation was illegal, even according to the communist law then in power [...], I realized we [homosexuals] needed more information; not just pornography but information” (18). Kisiel’s interest in Western culture recalls the influence of voguing in Angel Ulyanov’s Let’s Stir Things Up. The magazine was produced on a typewriter and photocopied by Kisiel at a copy shop, to then be published in Poland and abroad (19). It was self-financed, but was eventually commercialized in the second half of 1990. During the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, it provided regional and international statistics and information on medical developments and safer sex. This content provided Kisiel with a legal protection against possible statist restrictions (20). This copy of Filo is particularly interesting because it is one of the last underground editions of Filo before it was published in colour. Kisiel’s work prefigures what Radziszewski will do with the DIK Fagazine, but without the irony of the latter’s AIDS wallpaper. The Western influence is present in both magazines, but here it seems the focus is more on trying to make the LGBTQ+ community visible, making it reminiscent of an active gay and lesbian community after the fall of communism in Poland in 1989, a year in which the first Polish LGBTQ+ association was legalized. Radziszewski’s magazine is rather focused on the new contemporary strategy of commenting on the impossibility of this visibility.

Figure 4: Kisiel, Ryszard. Filo zin no. 1. Front Page, 1990, magazine, unknown dimensions, https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/_/fAE0i68TE1R8Pg.

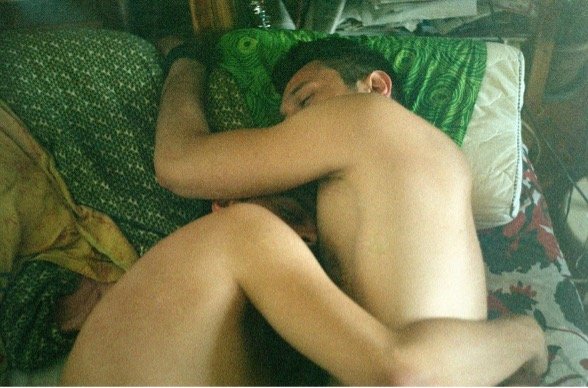

Lastly, like Guyvik, Polish artist Krystian Lipiec captures a peaceful moment of queer love (fig. 5). Here, the artist elects not to comment on any stereotype or conservative view of what constitutes Polishness. Lipiec instead invites the viewer into a private space, a place where queer people living in the post-Soviet world are expected to stay. However, the intimacy in this photograph is profoundly subversive; it asks the question: why shouldn’t this be public? Naked, the two men are free from any stereotype. They are not associated with disease, communism, masculinity, femininity, or even culture: they simply are. Is this what you want to see? The conservative Polish citizen will answer “no,” but this photograph is neither “too visible” nor “invisible.” It is only once artists like those previously mentioned reclaim queer stereotypes and desensitize the viewer that this picture will appear as nothing more than love to the post-Soviet eye. Ultimately, as the artist puts it, “being young, Polish, and queer doesn’t mean much…” (21).

Figure 5: Lipiec, Krystian. Untitled, Between Us Series, 2012, photograph, unknown dimensions, https://i-d.vice.com/en_us/article/xwmdmz/photos-that-celebrate-what-it-means-to-be-polish-and-queer.

In sum, this essay prompts important questions in the context of queer activism. By showing that post-Soviet culture and queerness are not mutually exclusive, and by playing with the idea of a queer Western ideology, artists have exposed the contradictions surrounding the invisibility-visibility dichotomy imposed by the state. Krystian Lipiec’s tender photograph, freed from stereotypes, culture, and ideology altogether, reminds the viewer to let go of their heteronormative gaze and accept to see queerness as unthreatening, loving, and free.

Endnotes

Richard C.M. Mole, “Constructing Soviet and post-Soviet sexualities,” in Soviet and Post-Soviet Sexualities, ed. Richard C.M. Mole (London, Routledge, 2019), 10.

Elzbieta Korolczuk, “The fight against ‘gender’ and ‘LGBT ideology’: new developments in Poland,” European Journal of Politics and Gender 3, no. 1 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1332/251510819X15744244471843.

Brian James Baer, “Now You See It: Gay (In)Visibility and the Performance of Post-Soviet Identity,” in Queer Visibility in Post-Socialist Cultures, ed. Nárcisz Fejes and Andrea P. Balogh (Bristol, Intellect Books Ltd, 2013), 39.

Baer, “Now You See It,” 38.

Baer, 40.

Mole, “Constructing Soviet and post-Soviet sexualities,” 10.

Mole, 7.

Baer, “Now You See it,” 50.

Baer, 41.

Baer, 41.

Lukasz Szulc, Transnational homosexuals in Poland: Cross-Border Flows in Gay and Lesbian Magazines (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 190, Springer Complete eBooks.

“In the face of official censure, Russia’s LGBTQ artists prove that their country has always been queer,” The Calvert Journal, Anastasiia Fedorava, 2 June 2019, https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/11300/in-the-face-of- official-censure-russias-lgbtq-artists-prove-that-their-country-has-always-been-queer.

Mole, “Constructing Soviet and post-Soviet sexualities,” 5.

Szulc, Transnational homosexuals in Poland, 144.

“This installation celebrates the faces of the Russian queer underground,” Dazed, Emily Dinsdale, 31 August 2020, https://www.dazeddigital.com/art-photography/article/50240/1/russian-queer-revolution-celebrates-lgbtq- underground-installation-vfd-gallery.

“This installation celebrates the faces of the Russian queer underground,” Dazed.

“Queer zines: making art from eastern Europe’s secret LGBTQ archives,” The Calvert Journal, Hannah Zafiropoulos, 24 January 2018, https://www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/9560/being-lgbtq-queer-archives- institute-karol-radziszewski.

Lukasz Szulc, Transnational homosexuals in Poland, 144.

Szulc, 146.

Szulc, 146.

“Candid photos that celebrate what it means to be young, polish, and queer,” i-D, Ryan White, 22 May 2018, https://i- d.vice.com/en_us/article/xwmdmz/photos-that-celebrate-what-it-means-to-be-polish-and-queer.