Influential Liminality: Eunuch Participation in Northern Song Dynasty Artistic Production and Collecting Practices

Written by Davin Luce

Edited by Will Schumer

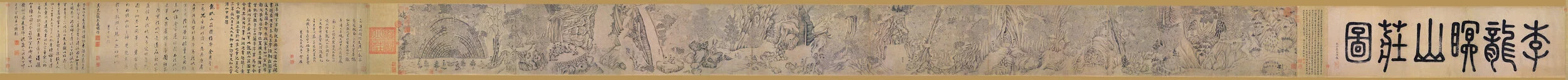

Figure 1: Qiao Zhongchang, Illustration to the Second Prose Poem on the Red Cliff, Northern Son dynasty. Handscroll, ink on paper, 30.48 x 1224.28 cm. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri.

The Northern Song dynasty (960-1127) is often characterised as a period in which artistic production flourished. The final emperor of the Northern Song, Huizong (r. 1100-1126), is not only known for his own artistic practice, but also his accumulation of artworks. During his reign, Huizong prompted a survey of his collection and the compilation of the Xuanhe huapu (Xuanhe Catalogue of Paintings), hereafter Xuanhe Catalogue [1]. In Accumulating Culture, cultural and gender historian Patricia Buckley Ebrey suggests that the practice of collecting is “fundamental to the ways knowledge is created, transmitted, and contested,”[2]. Historians tend to emphasize Huizong as the active force behind the imperial collection and catalogue. Art historian Amy McNair notes, however, that in the Xuanhe Catalogue the emperor is only present as a trace. In the catalogue’s entirety there are only three instances where the emperor is present, but he “never utters direct speech,”[3]. Considering McNair’s observation and Ebrey’s claim, individuals who participated in the compilation and those who contributed works to the Xuanhe Catalogue must also be considered. My intention is not to disregard Huizong’s role as collector, but rather add nuance to the subject through proposing another potential actor in this construction of knowledge: the imperial court eunuch.

What follows will act as an incubator for identifying the possibilities of how eunuchs may have affected the production and collection of artworks during the reign of Emperor Huizong. I will begin by locating the court eunuchs within the contemporaneous Chinese sociopolitical milieu and define them as liminal figures to demonstrate how their unique position provided them access to power and influence. Case studies of eunuchs will be considered throughout this essay in two capacities; firstly, eunuchs as patrons, collectors and donors featuring court eunuchs Liang Shicheng and Liu Yuan. These two case studies will demonstrate how eunuchs participated in the shift of stylistic interests of the period. The second category, eunuchs as painters, will feature Liu Yuan and Feng Jin to demonstrate how eunuchs were able to participate in contemporaneous political ideological debates through artistic production. While the categories I have proposed are not mutually exclusive, this loose framework will help to illuminate potential ways in which eunuch officials influenced the visual culture of the Northern Song dynasty.

Eunuchs are defined as “a castrated person[s] of the male sex,”[4] and have been in the employ of the rulers of China since the Shang dynasty (1600-1046 BCE). During certain historical periods, such as the Tang (618-907 CE) and the Ming (1368-1644 CE) dynasties, eunuchs were able to gain considerable political power and cultural influence. Located between these two dynasties, the Northern Song period marks an important transitional moment through which we can gain insight into the understanding of eunuchism’s sociopolitical and cultural significance. During the Northern Song, a eunuch’s ability to gain such power was severely limited in comparison to earlier and later eras. Historian Jennifer W. Jay points out that “living in an age so closely after the Tang, where eunuchs enthroned and dethroned emperors at will and dominated political and military arenas,”[5] eunuchs were regarded with fear and anxiety by imperial bureaucratic officials. This fear inspired by eunuchs was further elaborated in Xin Wudaishi (Historical Record of the Five Dynasties [907-960]) by Northern Song scholar-official Ouyang Xiu (1007-1072) [6]. Ouyang wrote that “[f]rom antiquity eunuchs have created havoc to the state; the source (of their threat) is more entrenched than that of the clamity [sic] of women. As for women, that is merely lust. The harm caused by eunuchs is not confined to merely one area,”[7]. The ostensible harm was, in part, due to eunuchs’ close proximity to imperial figures. Jay suggests that this close proximity was a source of anxiety because it bolstered their ability to gain the emperors trust and thus potentially “usurp the imperial prerogatives,”[8]. To theorize the unique social position of eunuchs in the Northern Song, I will now turn to the concept of liminality.

Liminality

The reasons for the anxieties discussed above reflects a eunuch’s unique position and identity within the imperial court. I argue that this unique situation was because eunuchs were liminal figures. Furthermore, I will argue that eunuchs were not simply liminal, but perpetually liminal social actors. The concept of liminality was first developed by French ethnographer Arnold van Gennep in The Rites of Passage (1909). Van Gennep conceptualized a tripartite classification of rites of passage in ritual: rites of separation (pre-liminal), rites of transition (liminal), and rites of incorporation (post-liminal) [9]. For van Gennep, the liminal phase occurred after crossing a threshold and was irreversible. This process is most apparent in his section on initiation rites, and more specifically puberty rites. Van Gennep suggests that rites of a sexual nature move an individual from an asexual world and incorporate them into a sexual one which is separated into groups by sex [10]. Rather than experiencing an initiation rite, I argue that eunuchs experienced a rite of expulsion. After castration, the eunuch was not reincorporated into society-at-large; instead, they were stuck in the liminal zone between the asexual and sexual worlds. Eunuchs were expelled from the larger social framework and yet were initiated into their own kind of community. As discussed above, however, this community’s standing in society was tainted by anxiety and fear.

Cultural anthropologist Victor Turner further developed liminality in The Ritual Process (1969). Turner defined liminal entities or people as “necessarily ambiguous…neither here nor there; they are betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremonial,”[11]. Jennifer W. Jay suggests even though eunuchs were castrati, their gender identity “remained unquestionably male,”[12]. The removal of the genitals, however, especially when voluntary, “contradicted the basis of Confucian society,” filial piety, “which held that the greatest crimes were to leave no heir and to harm the body given by parents,”[13]. As such, I suggest that even if eunuchs did not necessarily self-identify as liminal beings they remained betwixt and between Chinese customs and social conventions. Without the possibility of reincorporation into the larger social framework, the eunuch occupied a liminal social zone.

In their article ‘Transitional and Perpetual Liminality: An Identity Practice Perspective,’ published in Anthropology Southern Africa (2011), social anthropologists Sierk Ybema, Nie Beech, and Nick Ellis define ‘perpetually liminal’ as “manifesting when social actors occupy social positions which they experience as persistently ambiguous or ‘in-between,’”[14]. As eunuchs were unable to reincorporate (van Gennep’s post-liminal phase), (to borrow from van Gennep), their position is indeed persistent and permanent. Ybema, Beech and Ellis further elaborate on their theory stating that this perpetual position “entails being ‘drawn into extended circles of loyalty’ and ‘dwelling’ in liminal spaces,” and existing ‘“at the limits of existing structures,’”[15]. As I will argue below, eunuchs imagined and created extended circles of loyalty and existed at the limit of China’s existing social and political structures. As such, I propose that eunuchs in Imperial China were such perpetually liminal social actors. This unique social position was one of the defining factors which provided space for their participation in the production of art and collection building.

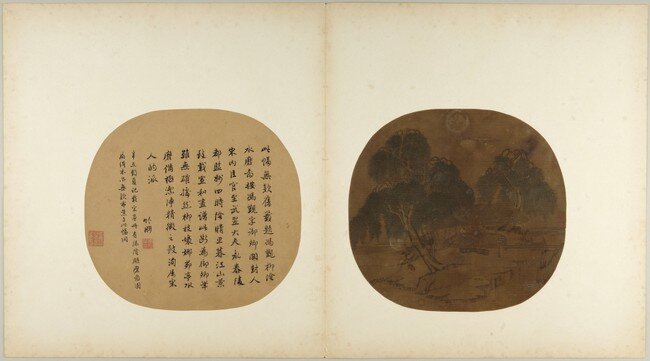

Figure 4: Li Gonglin, Mountain Villa, Northern Song dynasty. Handscroll, ink on paper, 28.9 x 364.6 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

Political climate of the Northern Song Dynasty

Having established eunuchs as perpetually liminal social actors, I will now undertake a brief political history of the Northern Song to illuminate discourses surrounding emperor-literati relations. Literati, or scholar-officials, were members of the imperial bureaucracy who acted as advisors to the emperor and headed various government offices and posts. During the Northern Song, literati were beginning to gain more political influence. As advisors to the throne, their lack of support for policy could cause frustration to the emperor and other literati. Patricia Ebrey notes that scholar-officials could “exert pressure on emperors by prolonged resistance to appointments and policies,” so while China was an autocracy “Song emperors were often frustrated by their inability to get their officials to comply with their wishes,”[16]. The relations between emperor-literati have important implications on the ways in which eunuchs participated in the imperial system, but also impacted how art was conceived and perceived in the Northern Song dynasty.

Figure 5: Detail from Mountain Villa by Li Gonglin.

The first century of the Northern Song dynasty is characterized by the promotion of scholarly pursuits. After Emperor Taizu (r. 960-976) seized the throne from the Zhou dynasty (951-960), he placed non-military men into governmental posts, thus beginning the shift from wu (military power) to wen (culture)[17]. The following two emperors continued the trend of expanding educational opportunities which led to the rise of the scholar-official class [18]. Historian and sinologist Peter Bol suggests that the early emperors of the Northern Song favoured scholar-officials over the military men because they “were willing subordinates, without independent power, who depended on a superior authority for their political position, and who brought to their duties a commitment to the civil culture invaluable to the institutionalization of central authority,”[19]. For Bol, the rise of scholar-officials reflects an “imperial desire to use men with ability but without a power base,” [20]. The final emperor of the first century of the Northern Song, Renzong (r. 1022-1063) [21], was a notable patron of Confucian education [22] who also nurtured a system of government criticism known as the Censorate. Ebrey points out that the “old office of the Censorate and the Bureau of Policy Criticism became under Renzong major organs through which literati could challenge and ultimately alter government policies and personnel,” [23].

Following the first century of the dynasty, an era of reforms began under Emperor Shenzong (r. 1067-1085). These reforms led to factional politics which persisted through the remainder of the period. It was within this factional political milieu that the powerful court eunuch Liang Shicheng (ca. 1063–1126) was able to gain substantial political and cultural influence at the court of Huizong. Liang began as an assistant in the Calligraphy Bureau and after the death of his superior, he was given charge of the imperial document storehouse. This position made him responsible for documents destined for the emperor and those leaving the emperor’s quarters. As Patricia Ebrey notes “Liang Shicheng so impressed Huizong that he awarded him a jinshi degree in the civil service examinations in 1109,”[24]. Liang would later be appointed the supervisor of the Palace Library, a position of significant prestige [25]. From about 1113 or 1114, Liang even performed tasks which had traditionally been reserved for chief ministers [26]. Liang’s rise to prominence in the imperial court system thus arose from his close contact with the emperor.

Figure 6: Detail, Li Gonglin after Gu Kaizhi, Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies, Northern Song dynasty. Handscroll, ink on paper, 27.9 × 600.5 cm. National Palace Museum, Beijing.

Figure 7: Detail, after Gu Kaizhi, Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies, Tang dynasty. Handscroll, ink and colours on silk, 24.37 x 343.75 cm. ©Trustees of the British Museum.

Liang’s lengthy period of imperial favor was rooted in reforms instigated by Shenzong between 1069-1073 known as the New Policies. These policies were “a program of fiscal, agricultural, educational, civil, and military policy initiatives promulgated by Wang Anshi [1021-1086],”[27]. Many conservative scholar-officials, such as Su Shi (1036-1101), vehemently opposed Wang Anshi’s New Policies. They saw these policies as benefitting the state while ignoring public welfare. As art historian and curator Leong Ping Foong points out, prior to the New Policies the emperor received much of his power from his role of “arbiter between dissenting camps of scholar officials,”[28]. Shenzong’s removal of the “principle of policy consensus system, wherein top officials were appointed based on their concurring positions” essentially eliminated the system of “checks and balances achieved through dissenting views in the central government,”[29]. Shenzong also divested the Censorate of its function and as a result “dissenting members were accused of obstructionism and dismissed,”[30]. The system set out by Shenzong continued into Huizong’s reign and is largely responsible for Liang’s rise to prominence; he was the imperial favorite who garnered unshakable trust from Emperor Huizong.

The New Policies led to several imperial-sanctioned and self-imposed exiles. One literatus who experienced both forms of exile in his lifetime was Su Shi. The life and literature of Su Shi would have a lasting effect on Liang Shicheng and by extension the visual and literary cultural of the Northern Song. Su was an anti-reformist scholar-official who was appointed a member of the Censorate when Shenzong was introducing the New Policies. As a member of the Censorate, Su wrote many criticisms of imperial policy. Unhappy with the Emperor’s repeated lack of response to his criticisms, Su asked for reassignment to the provinces in 1070. Later in the 1070s, Su Shi was arrested for slanderous poems against the imperial regime and was forbade to “speak out on government matters,”[31]. Rather than dampening Su Shi’s already prominent reputation, [32] this event bolstered Su’s fame.

When Huizong ascended the throne, he inherited a deeply divided political landscape. His policies tended towards supporting the reforms set out by Shenzong and Wang Anshi, [33] but he had attempted to reconcile the two factions during the first year of his reign. Eventually Huizong failed and sided with the reformist faction. In 1101, the emperor issued demotions to high-ranking conservative officials associated with the Yuanyou period (1086-1093)[34]. These demotions were both posthumous and imposed on those still living, such as Su Shi [35]. After a second series of demotion which again included Su Shi in 1102 [36], imperial orders were given in 1103 to destroy woodblock prints of Su Shi’s collected works [37]. It is within this divided political system that Liang Shicheng commissioned a handscroll painting of one of Su Shi’s most celebrated works.

The Eunuch as Patron, Collector and Donor

The following section will consider Liang Shicheng’s participation in the creation of Illustrations to the Second Prose Poem on the Red Cliff (Hou chibifu tu) (fig. 1) by Qiao Zhongchang (active 1120’s) which was the earliest illustration of Su Shi’s poem of the same name [38]. I will argue that it is due to his perpetual liminal position, which allowed him unprecedented access to Emperor Huizong, that Liang was able to navigate the very political circumstances which surrounded Su Shi. By utilizing art historian Lei Xue’s article “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial: The Nelson-Atkin’s Red Cliff Handscroll Revisited,” I will demonstrate that Liang Shicheng was likely the patron of the painting and that he was influential in the loosening of the restriction on Su Shi’s literary work.

The Red Cliff scroll was created in the monochrome baimiao style (‘plainline drawing’) of the painter Li Gonglin (1049-1106) but utilizes a more calligraphic and animated sensibility that much of Li’s oeuvre [39]. Li Gonglin is an interesting artistic model for the handscroll due to his politically liminal position; Li was close friends the political rivals Su Shi and Wang Anshi [40]. Perhaps Li’s political liminality resonated with Liang Shicheng, making Li an influential model for Liang’s self-fashioning. Li Gonglin was also one of the originators of the literati style of painting. Literati painting can be loosely defined as an amateur field of painting which was calligraphic in nature, most often used monochrome ink, featured unmodulated lines, had a sparse composition and was done in a more spontaneous manner. Rather than seeking verisimilitude or “virtuosic execution,” [41] associated with court-style painting, literati painting instead turned “toward the intellectual integrity of the piece,”[42]. Members of the literati favored the merit of the “executor, perhaps untrained in picture making but distinguished as a gentleman…his virtue, they argued, would be manifest in his spontaneous brushwork and its formal qualities,”[43]. In addition, literati works often included poetic or literary references. While many scholars point out that any stark definition or conceptual divide between literati and court aesthetic is not as distinct as originally thought [44], discourses surrounding the subtle distinction did exist at the time.

As Lei Xue points out, it was not just the style of the painting which the artist of the Red Cliff handscroll referenced. Qiao also referenced Li Gonglin’s narrative structure and formal qualities of the “hierarchically scaled figures and formulized drawing of houses,” which “Li often employed to distinguish his works from the realism of contemporary court paintings,”[45]. A section of Qiao’s handscroll (Fig. 2 and 3) demonstrates these methods. As Xue argues, however, this illustration “differs greatly from Li Gonglin’s literary illustrations,”[46]. Rather than following Li Gonglin’s “poetic intent,” [47] which was highly appreciated by literati painters [48], this work was a memorial painting [49]. Whereas typical literati landscapes tend to depict a generic or imagined landscape and the individuals who inhabit them as ‘types,’ Qiao’s painting depicts the Lin’gao Pavilion where “Su Shi spent the most meaningful years of his career,”[50]. The reference to a specific place and person in Qiao’s Red Cliff painting points to the memorial nature of the work [51].

An avid collector of art and antiquities, Liang Shicheng accumulated a collection which included many works by both Li Gonglin and Su Shi. As previously mentioned, at this time Su Shi’s literary works were supressed by the imperial court. The colophon attached to Qiao’s painting was completed only one month after a second imperial edict to destroy the printing blocks of Su Shi’s collected works [52]. The ability to patronize an artwork so closely related to Su Shi at this period in history is extraordinary. As I will suggest below, it was Liang’s close relationship with the Emperor which allowed him to be so bold; a relationship which was afforded to Liang through his perpetually liminal position in the imperial court. Another important point to note is Liang’s official biography in the Song shi (History of the Song). It states that Liang was Su Shi’s ‘expelled son’ who complained to the Emperor about the suppression of Su’s work. According to the Song shi, after this occurrence Su’s writings “gradually came out,” [53] emphasizing Liang’s influence at court. In a conversation featuring Liang which was reproduced in the Song shi as part of his biography, Liang also refers to Su as ‘late minister’ (xianchen). As Lei Xue suggests, this indicates that Su Shi was Liang’s late father. Furthermore, ‘late minister’ coupled with the phrase ‘expelled son’ denotes that Liang was an illegitimate son of Su Shi [54].

Another important factor in attributing the commission of this work to Liang is the placement of his seals. As Xue notes, the placement of Liang’s seals is consistent; they are all found on the joins of the sheets of paper [55]. This, combined with the absence of earlier seals [56], suggests that the process was carefully planned and executed [57]. The placement of the seals and the paintings memorial nature (a memorial painting was often not considered a commodity to be circulated) indicates that this work was likely commissioned by Liang Shicheng in person [58]. Liang’s choice of the artist Qiao Zhongchang, who quoted from the politically liminal Li Gonglin, combined with Liang’s insistence on a familial connection to the highly politicized Su Shi is highly suggestive. I postulate that Liang closely related his identity to figures who found themselves in ambiguous positions, caught betwixt and between. Furthermore, I argue that the fact that Emperor Huizong awarded Liang with a jinshi degree suggests that Liang made a concerted effort to self-fashion as a highly educated member of the literati class. As suggested by Ybema, Beech and Ellis’, perpetually liminal figures are often drawn into extended circles of loyalty. Perhaps due to Liang Shicheng’s liminality, he felt the need to create an imagined extended circle by connecting himself to Su Shi and the greater literati class.

Lei Xue ultimately argues that Liang Shicheng “played an important role in mediating, if not determining, the adoption of literati art, namely that of Li Gonglin, into court painting production,” [59]. Liang not only commissioned works in the style of Li Gonglin, he also coveted the originals. Quoting from the now lost epitaph of Li Gonglin, Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279) scholar-official Zhou Bida (1126-1204) wrote that the “‘official version’ of a Mountain Villa picture in the imperial collection was stolen by the eunuch official Liang Shicheng,’”[60]. Liang may have also acquired works by Li Gonglin for the imperial collection. While there are no contemporary records of this, a Southern Song writer wrote that Li’s Mountain Villa (Fig. 4 & 5) which was “the model for the Red Cliff painting, was ‘acquired by the eunuch Liang Shicheng,’”[61]. As Xue notes, Mountain Villa is included in the Xuanhe Catalogue, which could suggest “Liang’s direct participation in accumulating Li Gonglin works at court,”[62]. So, as Xue postulates, the role of eunuchs in the shift to a scholar-official sensibility in Chinese art production “might have been as important as that of emperor, and painters in the late Northern Song court,”[63].

Like Liang Shicheng, other eunuchs also collected important artworks, some of which were donated to the imperial collection and included in the Xuanhe Catalogue. As Amy McNair points out, eunuch official Liu Yuan (act. before 1093-d. after 1112) may have donated three famous antique works to Huizong’s collection: Gu Kaizhi’s Admonitions of the Court Instructress, Lu Hong’s Thatched Cottage, and The Night Outing of Lady Guoguo by Zhang Xuan. Yuan’s adoptive father, eunuch official Liu Youfang (act. Ca. 1067-1077), had “served as an advisor on art matters to Emperor Shenzong,” and was a renowned collector [64]. Youfang was known to have owned these three paintings, but their placement in the Xuanhe Catalogue suggests that they were added to the collection after 1100. As such, McNair postulates they were likely donated by Yuan, or his adoptive eunuch son [65]. The donation of these important works not only functioned to preserve cultural heritage, but also made them available for copying by court painters.

Figure 8: Attributed to Li Cheng, Tall Pines in a Level View, Five Dynasties or Early Northern Song. Hanging scroll, ink on silk, 126.1 x 205.6 cm, Chokaido Museum, Mie, Japan.

Figure 9: Anonymous (Song dynasty), in the style of Li Cheng, A Small Wintry Grove, Northern Song Dynasty. Hanging scroll, ink and light colors on silk 42.2 x 49.2 cam. National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

Figure 10: Guo Xi, Early Spring, 1072. Hanging scroll, ink and light colors on silk, 158.3 x 108.1 cm, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

The notion of copying artworks in the Chinese context does not carry the same negative connotations as it does in the modern western imagination. While the act of copying famous works has created problems for modern art historians, copying work was contemporaneously viewed as a positive and educational act [66]. In addition, as Patricia Ebrey notes, these copies were often highly collectible [67]. If the copyist was a prominent or famous individual, their copies could become as coveted as the originals. Of the three paintings donated by Liu Yuan, Emperor Huizong himself copied Zhang Xuan’s Lady Guoguo. Additionally, Li Gonglin is known to have copied of Lu Hong’s Thatched Roof, but the exact date when he completed the copy is unknown [68]. Ebrey also notes that Palace Library official, Dong You (fl. 1100-1130), referred to copies being made by court painters and library staff on several occasions [69]. Amy McNair hypothesizes that Li Gonglin, a scholar-official at court, could have created copies of famous antique works owned by the palace during his tenure at the imperial court by request to the emperor [70]. This suggests that while special permission may have been required to access the palace collection, it may have been available to more than just court painters for creating copies.

Li Gonglin is also known for his copy of Gu Kaizhi’s Admonitions (fig. 6) now at the Palace Museum in Beijing [71]. The oldest surviving copy of Admonitions (fig. 7) from the Tang period, now at the British Museum, bears a colophon by Emperor Huizong which suggests it was the version in the palace collection and the Xuanhe Catalogue. Comparing the two works, it is clear that Li Gonglin reinterpreted the Tang copy in a modern, literati mode. Copies done by well-known artist were often also copied by others, such as Li Gonglin’s version of Thatched Roof which was later copied by Lin Yanxiang (act. 1131-1162) [72]. As the instigator of the donation of these important works, the Liu Yuan not only contributed to the preservation of important cultural heritage, but also, by extension, facilitated the ‘modern’ interpretation of ancient works which impacted the visual culture of the Northern Song dynasty.

Eunuch as Painter

Having established that eunuchs were implicated in the patronage and donation of art, I will now turn to eunuchs as painters. Of the 231 painters included in the Xuanhe Catalogue, fourteen were eunuch officials [73]. Most of the paintings by palace eunuchs have been lost through history, but textual evidence from the Xuanhe Catalogue combined with a close reading of one extant painting will provide a productive lens through which to consider eunuchs as painters. The donor Liu Yuan, discussed above, was also a painter. His biography in the Xuanhe Catalogue states that Liu worked in the landscape genre in an untrammeled manner [74]. Untrammeled denotes a sense of freedom, non-restriction and spontaneity; all qualities greatly appreciated and practiced by the literati class [75]. Of the nine works listed in his entry in the catalogue, I will consider the first: ‘After Li Cheng’s Small Wintry Forest.’ The connection to Li Cheng presents an interesting paradox which will be discussed in further detail below.

Figure 11: Attributed to Feng Jin, Watermill Under the Willows, Song Dynasty. Round fan mounted as album leaf, ink and color on silk, 24 x 25.8 cm. The Arthur M. Sackler Collection, Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, New Jersey.

Tenth-century painter Li Cheng (919-967) painted landscape and tree-and-rock paintings. As Leong Ping Foong notes, “for scholars, ink landscapes and the tree-and-rock subjects were vehicles for expressing eremitic sentiments," which since at least the Han dynasty (206 BCE-226 CE) denoted a “resolute refusal to take public office and serve a corrupt government,” [76]. Even with these connotations, however, the imperial court eventually adopted Li Cheng’s style for their own purposes [77]. Many of Li Cheng’s one hundred fifty-nine paintings in the Xuanhe Catalogue reference a wintry forest scene [78]. A work attributed to Li Cheng entitled Tall Pines in a Level View (fig. 8) is representative of Li’s “primary subject matter – a level distance with ‘wintry trees’ – one that Li Cheng invented,”[79]. An anonymous painting in the style of Li Cheng entitled A Small Wintry Grove (fig. 9) also depicts a similar subject matter. While neither of these specific titles appear in the Xuanhe Catalogue, several similarly titled works do [80]. I postulate that works such as Tall Pines and Small Wintry Grove may have acted as models for Liu Yuan’s painting. As Tall Pines is attributed to Li Cheng and not an anonymous painting in his style, I will utilize it in the consideration of Liu Yuan’s painting.

Tall Pines is rendered in layered ink washes and depicts a rather barren landscape with two large pines in the left foreground. Between two rocky outcroppings in the foreground we see another distant pine tree in the center. The background depicts a rolling mountainous landscape with no sign of human habitation. The visual qualities of the work suggest the eremitic sentiment addressed above. This style, however, would become a favoured court aesthetic. The imperial court appropriated Li’s style to portray imperial power and authority through its ability to act “as visual representations of right to rule and good government,”[81]. As Foong puts it, Li Cheng was the “progenitor of a courtly artistic legacy to which Guo Xi [after 1000-ca.1090] was the natural heir,”[82]. The favored painter of Emperor Shenzong, Guo Xi, saw landscape paintings as analogous to cosmic power, imperial power, and benevolent governance,”[83]. Guo’s painting Early Spring (fig. 10), similar to Li Cheng’s Tall Pines, utilizes the symbol of the pine and mountainous landscape. In Guo’s depiction, however, the mountain (representative of the emperor’s authority) takes precedent while the pines (representative of Confucian scholars) are dwarfed [84]. In this reading of the image, the power of the emperor clearly overrules that of the Confucian scholar.

Figure 12: Detail of Feng Jin’s Watermill Under the Willows

As briefly mentioned above, considering Liu Yuan within this discourse presents an interesting paradox: A eunuch official who painted in an untrammeled manner to represent a subject which originally represented scholarly eremitism. The style, however, had by this point been appropriated to represent imperial authority and benevolence. If tall pines came to represent Confucian scholars, then Li Cheng’s painting emphasizes their prominence and hardiness. For a eunuch to place so much focus on wintry pines is noteworthy. As a liminal figure, the eunuch painter Liu Yuan depicted a sort of liminal representation which could have dualistic connotations. I suggest it was Liu Yuan’s perpetually liminal identity which informed this representation. Like Liang Shicheng, Liu identifies with scholar-officials through his manner of painting and his choice of subject matter. Due to his liminal position, however, Liu’s painting avoids negative reception and repercussion. This is evident through the paintings inclusion in the Xuanhe Catalogue. Had the painting not been well received, I postulate it would not have been included in the catalogue. Liu’s close proximity to the emperor and imperial court, provided through his liminal status, perhaps allowed him to explore potentially transgressive subject matter.

To further explore this avenue, I will now turn to the eunuch painter Feng Jin (dates unknown). In the Xuanhe Catalogue, Feng is described as being skillful at “lookouts in forest groves,” and able to provoke auditory experiences through his paintings, especially in Myriad Pipings of the Autumn Wind [85]. Describing this work, the author(s) of the catalogue wrote “[t]he imagination shown in this picture is profound, almost comparable to ‘Rhapsody on the Sounds of Autumn,’”[86] a poem by the scholar-official Ouyang Xiu [87]. This comparison is interesting considering Ouyang’s statement in Xin Wudaishi, discussed above, where he suggests the that the havoc and “harm caused by eunuchs is not confined to merely one area,”[88]. Ouyang Xiu was a prominent scholar-official whose works would likely have been known to Feng Jin. With the current available scholarship, it is impossible to prove that Feng Jin based his painting on Ouyang Xiu’s poem. I would postulate, however, that due to the very similar subject manner and the overt comparison by the author(s) of the Xuanhe Catalogue, it is possible Feng Jin painted Myriad Pipings of the Autumn Wind with the poem in mind. By referencing a prominent scholar-official, even one vehemently against eunuchs, Feng Jin may have been asserting his status as a cultured and learned individual. Through asserting this status, Feng Jin could have been equating his identity with that of the literati and creating imagined extended circles of loyalty like Liang Shicheng.

An extant painting attributed to Feng Jin entitled Watermill Under the Willows (fig. 11 & 12) is now at the Princeton University Art Museum. While this work is not listed in the Xuanhe Catalogue, it will provide an interesting comparison to another notable and roughly contemporaneous watermill painting now at the Shanghai Museum entitled The Water Mill previously attributed to Wei Xian. Feng Jin’s Watermill depicts a rather rudimentary watermill system in a forest grove with one individual and ox. The painting is rendered in a court-style sensibility with layered ink washes, colours and sense of planned execution. Art historian Heping Liu suggests that Shanghai Museum handscroll depicts a state-run watermill which is rendered in a style assigned to architectural subject matter known as jiehua style [89]. A section of the handscroll (fig. 13) shows the highly detailed, intricate and large watermill. The contrast between the size and context of these watermills requires further consideration. While watermills had been in use for over a thousand years by the Northern Song dynasty, Heping Liu points out that they had previously been private enterprises [90]. This contrast between Feng Jin’s painting and the Shanghai Museum painting thus had potential political implications.

Figure 13: Unknown artist, Section of The Water Mill, ca. 970s. Handscroll, ink and color on silk, 53.3 X 119.2 cm. Shanghai Museum

The interest in watermills began with Emperor Taizu, who established watermill agencies as state institutions for economic purposes. As Liu points out, these agencies were intended to “operate commercial watermills; to exhibit the imperial patronage of science and technology; and to exert bureaucratic control over the growing and profitable industry,”[91]. State interference in this previously private industry led to tension between the state and individuals. As Liu suggests the “water mill came to personify the ideal Confucian government of efficiency and benevolence as a consequence” of this tension [92]. Part of the reformist agenda in the New Policies was intended to restore the governments hold on industry after the loosening of the states hold between Taizu and Shenzong’s reigns. Conservative scholar-official and brother of Su Shi, Su Zhe (1039-1112), “fought for a more limited government, opposing the state’s active economic involvement at the cost of private interest,”[93]. So, another tension between the conservative faction of scholar-officials and the emperor is brought to light. I argue this tension is at play in Feng Jin’s depiction of a private watermill.

Conservative scholar-officials not only attempted to oppose these government policies; they also wrote poetry about the plight of the common watermill owner. The prominent scholar-official and good friend of Su Shi, Wen Tong (1018-1079), wrote a poem of this nature. An excerpt of ‘The Water Mill (Shuiwei).’ demonstrates the effects of state interference on the individual:

Despite toil and risk, the owner earns only a thin profit,

For generations his family made its living by the

riverbank;

Now the Sovereign is sending his men to supervise

Water conservancy.

Alas, what will the fate of these horizontal and vertical

water wheels be? [94].

The devaluation of the individual in the state-run economy mirrors the fate of conservative scholar-officials whose influence waned between Shenzong to Huizong’s reign. This poem demonstrates that the conservative faction’s clear interest in private industry and opposition to state intervention was a method to counter the autocratic power of the emperor. Considering the earlier conversation regarding the self-fashioning of eunuch officials as literati, I argue that Feng Jin’s painting has potential to be read as an institutional critique on the part of a eunuch painter. The connection to the circle of Su Shi and Ouyang Xiu demonstrates the notion of expanding one’s imagined circle of loyalty while residing on the edge of existing social and political structures. Feng’s watermill painting acts as a sort of double image that simultaneously belongs to the state through its stylistic mode, but echoes literati economic and social ideologies. In this way, Feng Jin’s Watermill is a liminal image produced by a perpetually liminal figure.

Conclusion

The goal of the current study has been to determine to what extent the eunuch affected the visual culture of the Northern Song dynasty. In this paper I have demonstrated that court eunuchs, in large part due to their perpetually liminal identity, do demonstrate potential influence on and contribution to Northern Song collecting practices and art production. I began by locating the eunuch within the larger sociopolitical context of the period, namely the expansion of the bureaucratic civil examination system led to an increased scholar-official class. Subsequently, factional political groups emerged later in the dynasty. I argued that this factional political milieu had implications on eunuchs participation in the visual culture but also on the art produced in the era. I suggested that eunuchs were able to gain cultural capital and influence during the Northern Song period largely due to their liminal position and that this position affected ways in which they self-fashioned.

The case study of Liang Shicheng demonstrated that eunuch patrons and collectors aided the adoption of a literati sensibility not only in art but also in literature. I suggested that the commission of Illustration to the Second Prose Poem on the Red Cliff by Qiao Zhongchang, who used the politically liminal Li Gonglin as a reference, and Liang’s insistence on his familial connection to Su Shi not only reflected an attempt to self-fashion as a member of the literati; it also mirrored the marginalization Su Shi and Liang Shicheng shared. By doing so, I argued that Liang Shicheng created an imagined extended circle of loyalty while existing on the edge of social structures. Liu Yuan, as collector and donor, not only participated in the preservation cultural heritage, but also facilitated modern interpretations of antique paintings which were highly collectible objects in their own right.

The case studies of eunuch painters, while not exhaustive, put forth the idea that eunuch painters moved more fluidly between literati and court sensibilities in their works. By citing Li Cheng, Liu Yuan not only referenced an originally literati mode, but he also referenced the contemporary imperial ideology. The mixture of these two modes is suggestive of a distinct ability to avoid criticism from the court which I argued was afforded by his liminal identity, but also pointed to his self-fashioning as a member of the literati. In addition, the mixture of styles points to the liminal status of the image itself. In the case study of eunuch painter Feng Jin, I postulated that the comparison between Feng Jin’s painting and Ouyang Xiu’s poem in the Xuanhe Catalogue is suggestive that Feng Jin had Ouyang’s poem in mind when creating his painting Myriad Pipings of the Autumn Wind. By doing so, Feng Jin, like Liang Shicheng and Liu Yuan, self-identified as a kind of literatus. The comparison between Feng’s painting Watermill Under the Willows and the Shanghai Museum’s painting The Water Mill acted to assert that Feng Jin was potentially participating in the debate surrounding state intervention on industry and the economy. By extension, I argued that Feng was making an institutional critique and expanding his imagined circles of loyalty while existing on the edge of social structures.

As discussed in the introduction, Patricia Ebrey noted that collecting participates in the construction of knowledge. With each of these case studies I have attempted to show how the eunuch did just that. Through their participation in constructing the imperial collection, they impacted the outcome. These case studies point to a common theme. Each of the eunuchs discussed seemed to be attempting to diminish the lacuna between their liminal identity and broader society by positing themselves as cultured and educated. Their perpetually liminal identity acted in two common ways. Firstly, their access to important individuals allowed them to take part in processes of collecting due to their ability to move around the palace freely. This aided their participation especially in commissioning works and acting as connoisseurs. Secondly, their liminal identity gave them a unique position from which they could explore motifs and themes which could have put them at risk for imperial backlash. Yet, they did so without such backlash. Thus, their liminal identity played a sort of doubled role, multiplying the potential for participation in and influence on collecting practices and art production of the Northern Song dynasty.

Endnotes

1. The catalogue was completed in 1120. See Amy McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue of Paintings: An Annotated Translation with Introduction (Ithaca, New York: East Asia Program, Cornell University, 2019), 1.

2. Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Accumulating Culture: The Collections of Emperor Huizong (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008), 3.

3. McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue, 4.

4. Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed (1989), s.v. “eunuch.”

5. Jennifer W. Jay, “Song Confucian Views on Eunuchs,” Chinese Culture: A Quarterly Review 35, no. 3 (1994): 46.

6. The Five Dynasties was a period of disunion between the Tang and Northern Song.

7. Ouyang Xiu, Xin Wudaishi (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1974), 38.406 quoted in Jay, “Song Confucian Views on Eunuchs,” 48.

8. Jay, “Song Confucian Views on Eunuchs,” 48.

9. Arnold van Gennep, The Rites of Passage (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960), 11.

10. van Gennep, The Rites of Passage, 67.

11. Victor W, Turner, The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1977), 95.

12. Jennifer W. Jay, “Another Side of Chinese Eunuch History: Castration, Marriage, Adoption, and Burial,” Canadian Journal of History/Annales Canadiennes d’Histoire 28, no. 3 (1993): 465.

13. Jay, “Another Side of Chinese Eunuch History,” 466.

14. Sierk Ybema, Nie Beech, and Nick Ellis, “Transitional and Perpetual Liminality: An Identity Practice Perspective,” Anthropology Southern Africa 34, no. 1–2 (2011): 24.

15. Ybema, Beech, and Ellis, “Transitional and Perpetual Liminality,” 24.

16. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 42.

17. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 23.

18. Taizong (r. 976-997) expanded the civil examination system, passing more individuals in one exam than Taizu had done in his whole reign. Zhenzong (r. 997-1022) favoured officials with literary talent and drew many scholars into the examination system from the south of China. See Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 22-29.

19. Peter Kees Bol, "This Culture of Ours": Intellectual Transitions in Tʼang and Sung China (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1992), 52.

20. Bol, "This Culture of Ours," 52.

21. Renzong was a child when he ascended the throne. His reign-proper began in 1033. See Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 27-29.

22. In 1043, he opened a school which admitted students regardless of the status of their father. See Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 29.

23. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 30.

24. Ebrey, Emperor Huizong (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2014), 338.

25. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 132.

26. Ebrey, Emperor Huizong, 341.

27. Leong Ping Foong, The Efficacious Landscape: On the Authorities of Painting at the Northern Song Court (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2015), 58.

28. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 59.

29. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 59.

30. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 59.

31. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 51. Su Shi was banished to Huangzhou.

32. Su Shi had received fame for passing the decree examination for “direct speech and full admonition” in 1061. He had received the highest score of the dynasty. See Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 50.

33. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 52-53.

34. The Yuanyou period (1086-1093) began when Empress Dowager Gao (1032–1093) seized the throne and promoted the conservative values of anti-reformist officials such as Sima Guang and Su Shi.

35. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 58.

36. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 60.

37. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 63.

38. Lei Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial: The Nelson-Atkins’s Red Cliff Handscroll Revisited” Archives of Asian Art 66, no.1 (2016): 25.

39. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 25.

40. An-yi Pan and 潘安儀, “Painting and Friendship, Political and Private Life: The Case of Li Gonglin,” Journal of Song-Yuan Studies, no. 30 (2000): 97–98.

41. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 4.

42. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 4.

43. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 4.

44. Art historian Jerome Silbergeld argues this simplistic binary is far more complex. Painting practice and scholarly values during the Song dynasty varied greatly, creating a near impossibility of considering a singular ‘literati style’ or ‘literati theory.’ Silbergeld writes “Song court and scholar-painters shared interests and stimulated each other with their creative innovations.” see Jerome Silbergeld, “On the Origins of Literati Painting in the Song Dynasty” in A Companion to Chinese Art, eds. Martin J. Powers and Katherine R. Tsiang (Chicester: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2015), 491. Patricia Ebrey also notes that any attempt to create a clear distinction between literati and court painting “was entirely on the literati side; the court and its painters valued versatility and were open to adopting new styles. The court took to collecting paintings by literati, as it long had collected their calligraphy.” See Patricia Ebrey, “Court Painting,” in A Companion to Chinese Art, eds. Martin J. Powers and Katherine R. Tsiang (Chicester: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2015), 32.

45. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 25.

46. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 26.

47. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 25.

48. Art historian Alfreda Murck suggests that “[w]hen a scholar-official communicated through the mute medium of landscape painting, he relied on a shared experience and knowledge of literature. The function, metaphors, and conventions of poetry informed and influenced the art of painting.” See Alfreda Murck, Poetry and Painting in Song China: The Subtle Art of Dissent (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center for the Harvard-Yenching Institute, 2000), 51.

49. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 26.

50. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 31.

51. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 32.

52. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 26. See also Ebrey, Emperor Huizong, 118 where Ebrey notes that “In the seventh month of 1123, one source reports, an edict ordered the destruction of the printing blocks for the collected works of Su Shi and Sima Guang, which someone in Fujian had had the audacity to have carved.”

53. Song shi (History of the Song), juan 468, 13663 quoted in Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 34. Jennifer W. Jay also points this out. She writes “In fact when Su Shi was disgraced, the eunuch Laing Shicheng defended him and reversed the official proscription of his writings.” See Jay, “Song Confucian Views on Eunuchs,” 47.

54. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 35.

55. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 33.

56. Seals were often impressed on paintings as a marker of ownership used by collectors. As works change hands, they accumulate seals by each owner.

57. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 36.

58. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 36.

59. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 37.

60. McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue, 186.

61. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 37.

62. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 37.

63. Xue, “The Literati, the Eunuch, and a Memorial,” 39.

64. McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue, 22.

65. McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue, 22.

66. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 273-274.

67. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 273.

68. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 273.

69. Ebrey, Accumulating Culture, 272.

70. McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue, 20.

71. Ankeney Weitz, Zhou Mi’s Record of Clouds and Mist Passing before One’s Eyes: An Annotated Translation (Leiden: Brill, 2002), 224.

72. Weitz, Zhou Mi’s Record of Clouds, 156.

73. McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue, 4. It is important to note that Ebrey suggests only nine eunuch painters. See Ebrey Accumulating Culture, 301. McNair’s monograph is the first full translation into English which she spent the last fourteen years translating. As such I will follow McNair’s count.

74. McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue, 278.

75. Chu-Tsing Li, “Trends in Modern Chinese Painting: (The C.A. Drenowatz Collection).” Artibus Asiae. Supplementum 36 (1979): 4.

76. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 21.

77. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 23.

78. McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue, 244.

79. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 120.

80. McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue, 245-246.

81. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 6.

82. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 113.

83. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 5.

84. Foong, The Efficacious Landscape, 9.

85. McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue, 281.

86. McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue, 281.

87. McNair, Xuanhe Catalogue, 281 n49.

88. Ouyang Xiu, Xin Wudaishi (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1974), 38.406 quoted in Jay, “Song Confucian Views,” 48.

89. Heping Liu, “‘The Water Mill’ and Northern Song Imperial Patronage of Art, Commerce, and Science,” The Art Bulletin 84, no. 4 (2002): 566.

90. Liu, “‘The Water Mill,’” 573.

91. Liu, “‘The Water Mill,’” 574.

92. Liu, “‘The Water Mill,’” 576.

93. Liu, “‘The Water Mill,’” 576.

94. Liu, “‘The Water Mill,’” 577.