The Fuller Brooch as an Anglo-Saxon Object

Written by Florence Plathan

Edited by Emily Vescio

In 2019, the International Society of Anglo-Saxonists changed their name to the International Society for the Study of Early Medieval England. This was following literary historian Mary Rambaran-Olm’s resignation as second vice-president of the organization, and her critique of the term “Anglo-Saxon.”1 In her article, “A Wrinkle in Medieval Time: Ironing Out the Problems of Periodization, Gatekeeping, and ‘Others’ in Early English Studies,” Rambaran-Olm argues not only that the term is anachronistic, as no one in pre-Norman England would have referred to themselves as “Anglo-Saxon”, but that it has been historically used to construct a myth of English racial unity and purity.2 Key historical figures in the Anglosphere such as Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Disraeli used this idea in comparing Germanic migration to the British Isles with the English colonization of North America, and in perpetuating a romanticized and racialized myth of medieval England to gain support of nationalist and imperialist policies respectively.3

Figure 1. Fuller Brooch (silver and niello, mid-to-late 9th century: British Museum, London).

Ultimately, the idea of an “Anglo-Saxon” England has primarily existed as a tool to propagate and reinforce English ethnonationalism and imperialism. Central to this idea is that the British Isles existed within a vacuum before the Norman conquest, that, as Rambaran-Olm states, “the early English period is viewed in absolutes: as formative, static, wholly white, and superior to something “other,” whatever “other” may be in the English historical narrative.”4 Therefore, the key to undermining this invented absolute “Englishness,” is in demonstrating England’s history of cultural hybridity. In the case of the Fuller Brooch (fig. 1), a ninth-century silver brooch which is often defined as quintessentially “Anglo-Saxon,” its roots to continental Europe are essential to this process. Though these connections stay largely within Europe, and by extension, whiteness, they destabilize “Englishness” as a category and aid in furthering an understanding of early medieval England, not as an insular, sealed world, but as one deeply connected with its neighbors.

In applying this framework to the Fuller Brooch, it is important to first understand it as an “Anglo-Saxon” object and investigate the ways in which its Englishness has been constructed, particularly in relation to the court of Alfred the Great. The brooch, made of silver and inlaid with niello, consists of an outer and inner ring. The outer ring contains sixteen circles, which are then separated in groups of four by scored lines at the cardinal points. Within these groups of four, each circle contains either a human figure, a circular vegetal design, and two intricate animals, one a quadruped and the other more birdlike. In terms of iconography, the order of images reflects along the vertical line of the brooch (with some deviance, note the southeast section where the human and vegetal sandwich on the animal, unlike the alternating pattern on the rest of the brooch). The inner ring divides into five sections, again separated by scored lines. The central section is a curved cross, with the remaining sections as lozenges, each containing one the five senses. Sight takes the central cross and dominates the composition. They are front facing with large bulging eyes, identifying themselves as Sight, and holds two cornucopias which later develop into arrow motifs on the right and left corners of the curved cross shape. Furthermore, this arrow motif is replicated both above Sight’s head, there as three arrows on top of each other, and on either side of their head in an interlocking triangle pattern. In many ways, Sight echoes the human figures in the outer ring. Though, without Sight’s bulging eyes, much of the facial features of the figures (namely their middle-parted hair, drooping ears, and connected mouth and lips) are similar to Sight’s, and the vegetal motifs on either side of their heads echo the cornucopias in Sight's hands. This strengthens the brooch’s sense of formal unity and aesthetic harmony.

Both of these elements are furthered in the inner lozenges, as the interlocking triangle and arrow patterns surround the smaller sense figures. Each of the figures are upward facing and in side profile. Clockwise, the first figure is that of Smell. Being the most difficult to display in action and rather than displaying an enlarged version of the organ in question (as was done with Sight), Smell hides their hands to emphasize their face’s proximity to the arrow motif, which is connected to a vegetal motif beneath their feet (in turn, echoing Sight’s cornucopias). Moving then to Touch, who identifies themselves through action. Though far more obvious than the ambiguous action of smelling, in clasping their hands together, Touch is cemented as both a sense and an action, a theme that is replicated throughout the inner lozenges. Hearing, for example, is either running or dancing, being the only one of the figures with bent legs and holding their left hand up to their ears.5 The last of the figures, Taste, continues this emphasis on action as they shove their hand into their mouth. United in both similar vegetal decorative elements and by identifying themselves through action, these figures, and by extension Sight and the outer ring, create a sense of internal rhythm in the piece.6

Beyond aesthetic unity, the many elements of the brooch share an iconographic programme. Under the court of Alfred the Great, Wessex saw a revitalized interest in intellectual production, largely spearheaded by Alfred himself. A major element of this was the rise of a cult of spiritual wisdom and emphasis upon the role of the “mind’s eye” in contacting and receiving heavenly wisdom.7 Sight was understood as key to this process, and in the Fuller Brooch, it takes primacy over the other senses. To gain heavenly wisdom, men were to move beyond the limited perceptions of the senses and realize the eternal gifts of their soul through “proper exercise” of his mental virtues or cræftas via his mind’s eye.8 Some have argued that the hierarchical distinctions between the senses are not as firm as originally believed, owing mainly to the role of Hearing in the way the rhythms of the brooch’s dense composition is initially perceived in auditory terms.9 However, even if the distinctions between the senses are not definitive, it is clear, in both the centrality and comparative size of Sight, that it is intended to be the main focus of the work. This is furthered through the similarities between Sight and the human figures in the outer ring. In fact, all of the figures in the outer ring are intended to represent the diversity of Creation10 and in the human figures’ similarity to Sight, suggests God’s role in granting humanity the senses while recognizing the separation between his eternal, spiritual qualities from his quotidian existence.11 Thus, Sight and the conception of a “mind’s eye” is reinforced as the central meaning of the work.

This complex iconographic program is, in some ways, at odds with the apparent levity of the work. In the Trewhiddle style that dominated English metalwork in the 9th century, it is hard to ignore not only the intricate rhythms of the brooch’s composition, but its eccentric representation of the five senses. The bulging eyes of Sight and Taste’s hand shoved in its own mouth indicate a certain degree of whimsy to the piece, which could have been ignored for a didactic representation of spiritual wisdom and the “mind’s eye.” Thus, there is on one level a combination of the secular and the sacred, in the use of ostensibly secular imagery to demonstrate the intellectual pursuit of spiritual and divine wisdom. On another level, there is a dichotomy between its subject matter and the way its subject matter is represented. It both displays ideas of serious intellectual thought, deeply connected to Alfred’s own court, and a sense of rhythm, joy, and wonder.

Figure 2. Alfred Jewel (gold, rock crystal, enamel, c. 871-99: Ashmolean Museum, Oxford).

This sense of eccentricity can be connected to its role in Alfred’s court more broadly. Unfortunately, nothing is known of the production or provenance of the brooch, as it was not known widely until 1910 when it was published in The Antiquary12 after its purchase from, what Sir Charles Robinson described as “a London bric-a-brac dealer.”13 That being said, the brooch has been connected to a political culture of royal gift-giving in ninth-century Wessex. Alfred and his predecessors monopolized gift-giving in their kingdom, using it as a tool to inspire fealty in their subjects.14 Another object identified as an Alfredian gift is the Alfred Jewel (fig. 2), a gold encased rock crystal with cloisonné enamel depicting a male figure. The jewel is more readily identifiable as an Alfredian object than the brooch, as its inscription on the side states “ÆLFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN” or “Alfred commanded me to be made.”15 The jewel is believed to have been the end of an æstel, essentially a pointer for reading manuscripts (like the brooch, leading the owner back to the word of God as interpreted by Alfred),16 and as the enamel figure in the jewel is commonly identified as Sight,17 connects to Alfred’s intellectual program and its interest in the “mind’s eye.” However, it is important to note how both of these works functioned as objects in their quotidian existence. The close inspection granted to us was virtually non-existent for all but the object’s owners. The brooch, for example, as a piece of jewelry, would have been only one element of its wearers dress and therefore, been subsumed by other aspects of its wearer’s appearance.18 As David Pratt states, “Whether worn by a king’s thegn, or on the royal shoulder, the brooch amounted to a central prop within Alfred’s personal theater, demonstrative of royal philosophy.”19 One can then argue that, in their splendor, these objects were not wholly intended to be seen as universal symbols of the owner’s wealth, but rather, to forge a private connection between owner and object, and by extension, subject and king.

Here, the image of the brooch that arises is one that is deeply connected to the court of Alfred the Great in both its iconographic program and social function. Thus, it is difficult to fully separate the brooch from its Alfredian context and the king’s place in English national myth. Alfred, after all, is not simply known as Alfred, but as Alfred the Great. He holds a distinct place in English history in both public memory and historiography. For the Victorians, he was a symbol of English nationalism and its supposed inherent freedoms,20 while in academic literature, he has been stated to have “[laid] the foundations for the creation of an English nation.”21 Furthermore, historical analysis of his reign often relies on sources such as Asser’s Life of King Alfred and the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, which have been accused of being biased or propagandistic.22

Though the work is deeply embedded in Alfred’s court and intellectual program, it can also be understood as material evidence of Alfred’s relationships to continental Europe. First, it is important to note that Alfred did not rule over an united England. In fact, it was during his rule that the lower half of Great Britain was divided into the Danelaw, a Scandinavian territory which was the result of Viking encroachment, and several English kingdoms. Therefore, it is key to understand Alfred’s Wessex as a political and cultural space keenly aware of its neighbors, both as cultural and religious others. It is not difficult to imagine that Christianity and Christian philosophy as represented in the Fuller Brooch could be seen as a stark contrast to Scandinavian paganism. Despite this there are similarities in the zoomorphic motifs of the brooch and those of the Hoven sword hilt, found in modern-day Norway,23 suggesting a more porous than rigid border between the two halves of this region. Second, in terms of his connections to the Carolingian Empire, not only did Alfred draw from Charlemagne’s reforms and share the Carolingian inspiration from Rome, but also visited the continent as a child.24 In 853, his father, Æthelwulf, took him to Rome to visit Pope Leo IV, and on their return, spent a prolonged period in the court of Charles the Bald. There, Æthelwulf married Judith of Flanders, who, briefly exerted a degree of influence over the West Saxon court when they returned to Wessex.25 At a young and highly impressionable age, Alfred had sustained contact with the Carolingian Empire, where he inherited and reacted to ideas of Solomonic kingship26 and dynastic consciousness,27 something which would continue later into his life.

When launching his program of intellectual reform, Alfred contacted Carolingians both on the continent and in his court. For example, his letter to Fulk, Archbishop of Reims remains a key text in understanding the Alfredian court.28 Beyond this, Alfred invited Grimbald of St. Bertin, a Benedictine monk from what is today Northern France, to assist him in his literary pursuits. John the Old Saxon, a West Frankish priest, was involved in the court’s ecclesiastical policy.29 Furthermore, Alfred brought craftsmen “from many races”, including Carolingians, to Wessex.30 Though it is unclear if any of these craftsmen were involved in the production of the Fuller Brooch, it is difficult to ignore that it was created within a context of cultural and intellectual exchange with continental Europe, especially as an object representative of and closely tied to Alfred’s intellectual output, something directly influenced by his Carolingian contacts and interactions with its court.

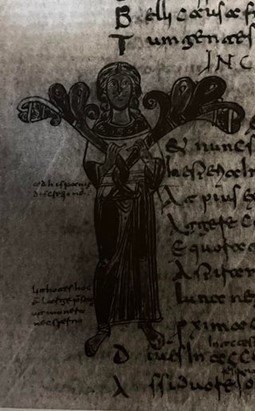

Figure 3. Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale, lat. 6, fol. 111. In Court Culture in the Early Middle Ages: The Proceedings of the First Alcuin Conference, edited by Catherine Cubitt, 219. Turnhout: Brepols, 2003.

However, the Fuller Brooch’s continental connections do not lie purely in its connection to a wider culture of foreign exchange and influence. The central figure of Sight in holding two cornucopias, in fact is quite similar to both the Insular “Osiris pose” and its supposed origin, the rod-holders in Eastern and Mediterranean traditions. In some ways it is comparable to a figure in an early 10th century Beneventan manuscript (fig. 3), with its down-turned ears, center part, and similar pose, replete with lobed plant stems.31 Altogether, this suggests that the brooch is a part of wider cultural traditions which, through centuries-long processes of exchange, migration, and adaptation, brought styles and motifs from the continent and situated themselves within a British context.

This wider cultural tradition is further evidenced by the brooch’s role as a key example of the Trewhiddle style which dominated ninth-century English metalwork. Named after the Trewhiddle Hoard, first found in the late eighteenth century, the style is characterized by its frequent use of silver and niello, with silver being a luxury material being increasingly brought to England through Scandinavia, and its use of intricate zoomorphic and vegetal ornamentation.32 This style, though unique to ninth-century English kingdoms, can be framed as a direct, and at times, even overlapping successor to the Mercian style of the eighth century, displaying similar patterns of ornamentation and motif.33 Both of these styles, though largely confined to the British Isles, must be understood within their genealogy as products of Germanic migration to Britain following the end of Roman rule and Celtic traditions of across the islands. In the brooch itself, this can be seen in its zoomorphic elements, which are themselves apart of a tradition of representing animals which dates back to the fifth century34 during the first waves of Germanic migration, and its vegetal motifs, a legacy of Celtic ornamentation in its curvilinear design and interlocking patterns.35

In this light, the Trewhiddle style is on one hand, largely geographically constrained to England, but on the other, stems from a centuries long process of adaptation, development, and cultural hybridity as a result of Germanic migration. Though proponents of the “Anglo-Saxon” myth have often utilized England’s Germanic history, the style’s connections to the isles’ Celtic populations and its use as a primarily aristocratic style in a court with key connections to the continent, serve to undermine this.36 By stating that styles and motifs which are often understood as uniquely English have within them, deep and traceable connections outside of England, it becomes clear that Englishness does not exist, nor did it develop, within a cultural vacuum.

Therefore, though we can regard the Fuller Brooch as an “Anglo-Saxon” object, this label both obscures the work’s cultural context and continental connections and reinforces a mythic history of Englishness. One could argue that the brooch in itself is not a monumental aspect of the legend of Alfred presented in the nineteenth century, however, this argument, in limiting itself to only direct manipulations, ignores the wider ramifications of ethnonationalism. If the brooch is understood as an object of a particular court, it is essential to then, to scrutinize and critique what is known of said court. Altogether, since its relationship to Alfredian thought and strategies of political kinship are essential to our understanding of the brooch as an object, it is impossible to separate it from Alfred’s court. So, in destabilizing the category of rigid and propagandistic Englishness that is commonly associated with Alfred, the brooch becomes a way to demonstrate the realities of English life in the ninth century, that it was deeply enmeshed with its neighbors, and the recipient of a centuries-long history of cultural hybridity. In this light, the Fuller Brooch is, though still deeply connected to its political and social circumstances, a product of a cultural sphere of exchange and migration in Northwestern Europe.

Endnotes

“Message from the Advisory Board (19 September 2019),” International Society for the Study of Early Medieval England, last modified, September 19, 2019, isasweb.net/AB091919.html.

Mary Rambaran-Olm, “Misnaming the Medieval: Rejecting “Anglo-Saxon” Studies,” History Workshop Online, November 12, 2022, historyworkshop.org.uk/misnaming-the-medieval-rejecting-anglo-saxon studies/?fbclid=IwAR1EndSzaJOhf8mTirqWBx434G-_Ehu9OYOk3eKBUhJOiLBqKCDNifD8p44.

Mary Rambaran-Olm, “A Wrinkle in Medieval Time: Ironing Out the Problems of Periodization, Gatekeeping, and "Others" in Early English Studies,” New Literary History 52, no.1 (2021): 391.

Rambaran-Olm, “A Wrinkle in Medieval Time,” 391.

Martha Bayless, “The Fuller Brooch and Anglo-Saxon Depictions of Dance,” Anglo-Saxon England 47, no. 1 (2016): 211-12. doi.org/10.1017/S0263675100080261.

Melissa Herman, “Sensing Iconography: Ornamentation, Material, and Sensuousness in Early Anglo-Saxon Metalwork,” in Sensory Reflections: Traces of Experience in Medieval Artifacts, ed. Fiona Griffiths and Kathryn Starkey (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2018), 106-7. doi.org/10.1515/9783110563443- 005.

David Pratt, The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 188- 90.

Pratt, The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great, 188.

Herman, “Sensing Iconography,” 103-7.

Pratt, The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great, 187-88.

Pratt, The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great, 188.

Sir Charles Robinson, “An Anglo-Saxon Brooch,” The Antiquary 46, no. 10 (1910): 268-9. archive.org/details/antiquarymagazin46londuoft.

R.L.S. Bruce-Mitford, “Late Saxon Disc-Brooches,” in Dark-Age Britain: Studies presented to E.T. Leeds with a bibliography of his works, ed. D.B. Harden (London: Methuen & Co., 1956), 173.

Pratt, The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great, 38.

Leslie Webster, Anglo-Saxon Art: A New History (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012), 154.

Pratt, The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great, 189.

Egil Bakka, “The Alfred Jewel and Sight,” Antiquaries Journal 46, no. 2 (1966): 277-82. doi.org/10.1017/S0003581500053294.

Alexandra Knox, “Middle Anglo-Saxon Dress Accessories in Life and Death: Expressions of a Worldview,” in Dress and Society: Contributions from Archaeology, ed. Toby F. Martin and Rosie Weetch (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2017), 126-7. ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mcgill/detail.action?docID=4805220.

Pratt, The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great, 189.

Pratt, The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great, 1.

Michelle P. Brown, The Book of Cerne: Prayer, Patronage and Power in Ninth-Century England (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 18.

Pratt, The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great, 2-4.

Bruce-Mitford, “Late Saxon Disc-Brooches,” 182.

Janet Nelson, “Alfred’s Carolingian Contemporaries,” in Alfred the Great: Papers from the Eleventh Centenary Conferences, ed. Timothy Reuter (London: Routledge, 2003), 297. doi.org/10.4324/9781315262932.

Janet Nelson, “Alfred’s Carolingian Contemporaries,” 293-98.

Leslie Webster, “Ædificia Nova: Treasures of Alfred’s Reign,” in Alfred the Great: Papers from the Eleventh Centenary Conferences, ed. Timothy Reuter (London: Routledge, 2003), 101. doi.org/10.4324/9781315262932.

Janet Nelson, “Alfred’s Carolingian Contemporaries,” 303-4.

Janet Nelson, “‘… sicut olm gens Francorum … nunc gens Anglorum’: Fulk’s Letter to Alfred Revisited,” in Ruler and Ruling Families in Early Medieval Europe: Alfred, Charles the Bald, and Others (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 1999), 135-37.

Pratt, The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great, 57-62.

Pratt, The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great, 185.

David Pratt, “Persuasion and Invention at the Court of King Alfred the Great,” in Court Culture in the Early Middle Ages: The Proceedings of the First Alcuin Conference, ed. Catherine Cubitt (Turnhout: Brepols, 2003), 216- 20.

Webster, Anglo-Saxon Art, 146-52.

Rosie Weetch, “Brooches in Late Anglo-Saxon England within a North West European Context: a study of social identities between the eighth and twelfth centuries” (PhD diss., University of Reading, 2014), 190-94.

David Wilson and C.E. Blunt, “The Trewhiddle Hoard,” Archaeologia 98, no.1 (1961): 102. doi.org/10.1017/S0261340900010055.

Bruce-Mitford, “Late Saxon Disc-Brooches,” 180.

Webster, Anglo-Saxon Art, 150-52.

Bibliography

Bakka, Egil. “The Alfred Jewel and Sight.” Antiquaries Journal 46, no. 2 (1966): 277-82. doi.org/10.1017/S0003581500053294.

Bayless, Martha. “The Fuller Brooch and Anglo-Saxon Depictions of Dance.” Anglo-Saxon England 47, no. 1 (2016): 183-212. doi.org/10.1017/S0263675100080261.

Brown, Michelle P. The Book of Cerne: Prayer, Patronage and Power in Ninth-Century England. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996.

Bruce-Mitford, R.L.S. “Late Saxon Disc-Brooches.” In Dark-Age Britain: Studies presented to E.T. Leeds with a bibliography of his works, edited by D.B. Harden, 171-201. London: Methuen & Co., 1956.

Herman, Melissa. “Sensing Iconography: Ornamentation, Material, and Sensuousness in Early Anglo-Saxon Metalwork.” In Sensory Reflections: Traces of Experience in Medieval Artifacts, edited by Fiona Griffiths and Kathryn Starkey, 97-115. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2018. doi.org/10.1515/9783110563443-005.

International Society for the Study of Early Medieval England. “Message from the Advisory Board (19 September 2019)” Last modified, September 19, 2019. isasweb.net/AB091919.html.

Knox, Alexandra. “Middle Anglo-Saxon Dress Accessories in Life and Death: Expressions of a Worldview.” In Dress and Society: Contributions from Archaeology, edited by Toby F. Martin and Rosie Weetch, 112-29. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2017.

Nelson, Janet. “Alfred’s Carolingian Contemporaries.” In Alfred the Great: Papers from the Eleventh Centenary Conferences, edited by Timothy Reuter, 293-310. London: Routledge, 2003. doi.org/10.4324/9781315262932.

Nelson, Janet. “’… sicut olm gens Francorum … nunc gens Anglorum’: Fulk’s Letter to Alfred Revisited.” In Ruler and Ruling Families in Early Medieval Europe: Alfred, Charles the Bald, and Others, 135-44. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 1999.

Pratt, David. “Persuasion and Invention at the Court of King Alfred the Great.” In Court Culture in the Early Middle Ages: The Proceedings of the First Alcuin Conference, edited by Catherine Cubitt, 190-221. Turnhout: Brepols, 2003.

Pratt, David. The Political Thought of King Alfred the Great. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Rambaran-Olm, Mary. “Misnaming the Medieval: Rejecting “Anglo-Saxon” Studies.” History Workshop Online, November 12, 2022. historyworkshop.org.uk/misnaming-the-medieval-rejecting-anglo-saxon-studies/?fbclid=IwAR1EndSzaJOhf8mTirqWBx434G-_Ehu9OYOk3eKBUhJOiLBqKCDNifD8p44.

Rambaran-Olm, Mary. “A Wrinkle in Medieval Time: Ironing Out the Problems of Periodization, Gatekeeping, and "Others" in Early English Studies.” New Literary History 52, no.1 (2021): 385-406.

Robinson, Sir Charles. “An Anglo-Saxon Brooch.” The Antiquary 46, no. 10 (1910): 268-9. archive.org/details/antiquarymagazin46londuoft.

Webster, Leslie. “Ædificia Nova: Treasures of Alfred’s Reign.” In Alfred the Great: Papers from the Eleventh Centenary Conferences, edited by Timothy Reuter, 79-103. London: Routledge, 2003. https://doi-org.proxy3.library.mcgill.ca/10.4324/9781315262932.

Webster, Leslie. Anglo-Saxon Art: A New History. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012.

Weetch, Rosie. “Brooches in Late Anglo-Saxon England within a North West European Context: a study of social identities between the eighth and twelfth centuries.” PhD diss., University of Reading, 2014.

Wilson, David and C.E. Blunt. “The Trewhiddle Hoard.” Archaeologia 98, no.1 (1961): 75-122. doi.org/10.1017/S0261340900010055.