Dolls that Appall: An Analysis of “Black Canadiana Memorabilia” through “Mammy” and “Topsy” Stereotypes in Twentieth Century Canadian Dolls

Written by Emily Draicchio

Edited by Ellie Finkelstein and Alicia Wilson

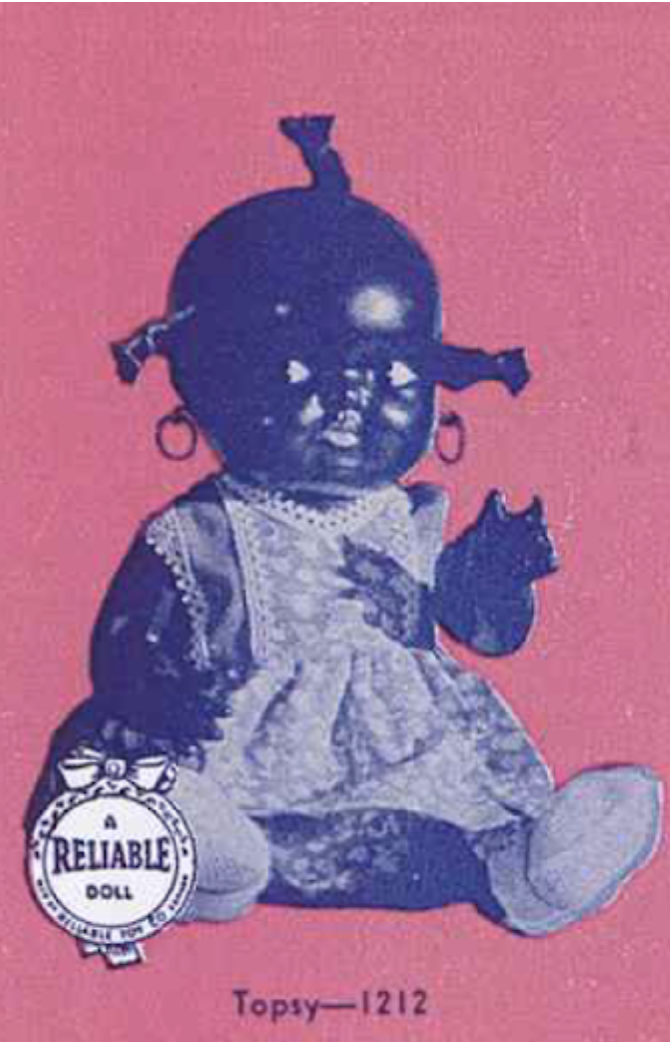

Dolls, like other artifacts of material culture, can be studied to reveal different cultural attitudes and values in society depending on the time and place in which they were generated. This is most telling in mass-produced toys that intentionally try to appeal to dominant attitudes, In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this usually entailed catering to white values.1 As a result, grossly caricatured dolls were produced for white people who felt threatened by the abolition of slavery.2 Specifically, anti-black dolls, or “contemptible collectibles,” birthed in the American context as “Black Americana memorabilia” that perpetuated several types of caricatures associated with black people.3 However, “black Canadiana memorabilia” also exists for similar anti-black dolls have been manufactured and collected in Canadian toy factories and museums. These include Topsy-1212 [Fig. 1 & 2] and Black Female Doll holding White Child [Fig.5] that both date to the early twentieth century.

Fig. 1: Reliable Dolls, Topsy-1212 (c.1930-1940), Composition, Various sizes available from 10 inches to 20 inches, Canadian Museum of History, Quebec, Canada. In Reliable Dolls 1940 Catalogue.

As such, the lack of acknowledgement that contemptible collectibles exist, and were produced in Canada, attests to the myth of Canada as tolerant, inclusive and racism-free. This ignores the nation’s brutal colonial history of conquest and cultural genocide and4 follows the trope that slavery, blackface and segregation were racist institutions brought into Canada from America.5 Through an analysis of Topsy-1212 and Black Female Doll holding White Child, we will see that twentieth century Canadian dolls perpetuate the “pickaninny” and “mammy” stereotypes respectively, and are inextricably linked to Canada’s history of slavery, segregation and minstrelsy. In doing so, this paper will serve to challenge the myth of Canada as a racism-free nation.6

The objective of this paper is threefold; first it will display the presence of contemptible collectibles in a Canadian context through caricatured black “pickaninny” and “mammy” dolls. Second, the re-contextualization and analysis of the socio-cultural meanings of Topsy-1212 and Black Female Doll holding White Child will attest to Canada’s involvement in slavery, minstrelsy and segregation.7 Lastly, by tracing the impacts and evolution of racism in Canadian history through stereotyped dolls, the myth that Canada is a victim of racism that originates elsewhere will be further problematized.8

The term contemptible collectible was coined by Patricia A. Turner , professor in World Arts and Cultures and African-American Studies at UCLA, as an alternative framework for “Black Americana memorabilia,” an umbrella term once used to describe both the production of images by blacks and images of blacks.9 Instead, contemptible collectibles are images of black people made by white people. They are artifacts that display insidious iconography related to racism and anti-black stereotypes.10 Anti-black products were both handmade and mass produced and are still made and purchased today.11 Due to their mass-production, contemptible collectibles have not yet received adequate scholarly attention as they are considered “low art”.12

Contemptible collectibles reinforce derogatory images of black people to a “limited range of social and political possibilities.”13 This is reflected in exaggerated physical characteristics and clothing that emphasize a narrow array of different statuses and occupational roles deemed acceptable for a black person. Importantly, these items are everyday objects, which, both consciously and unconsciously, perpetuate stereotypes that become normalised and accepted by society.14 The caricatured depictions of black subjects in material culture has in turn (re)produced several stereotypes, including the brute, coon, pickaninny, Uncle Tom, Aunt Jemima, mammy, Sapphire, Jezebel, golliwog, tragic mulatto, and so on.15 These stereotypes were produced during the institution of slavery and after the period of abolition as a symbolic way to continue the purchasing and selling of “the souls of black folk.” 16This further reinforced new racist ideologies, that according to Turner, were practiced primarily by Americans.17

The production of such items was not contained to North America. In fact, these dolls were “produced in the United Sates, Europe, and Asia from the 1880s-1950s.” 18 According to Kenneth W. Goings, professor of African American and African Studies at Ohio State University, antiblack dolls were developed, produced and manufactured by white Americans after the Reconstruction era due to an increase in consumerism and subsequently advertisements.19 As such, contemptible collectibles were “created” by manufacturers who drew inspiration from pre-existing dominant public sentiments towards black Americans.20 This history of contemptible collectibles in America can also be extended to Canada. Therefore, although Turner and Goings’ research only discusses contemptible collectibles in an American context, I suggest that there also exists “Black Canadian memorabilia” that perpetuates the same stereotypes previously listed . Two popular stereotypes that will be discussed below in the form of Canadian dolls include the “pickaninny” as Topsy and “mammy”.

Fig. 2: Reliable Dolls, Topsy-1212 (c.1930-1940), Composition not original clothing[?], 17 inches, Private Collection, Toronto, Canada.

The word “pickaninny” derives from the Portuguese word “pequenino,” which refers to a tiny person.21 During the period of slavery, the term “pequenino” was vulgarised to “pickaninny,” which is a racial slur used to denote a child of African descent who was perceived as malnourished and underdeveloped.22 The “pickaninny” stereotype emerged from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s character of Topsy in her well-known book Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852).23 Topsy was depicted as a dishonest enslaved black girl with a slovenly appearance living in Kentucky.24 Topsy was described as a young child, about eight years old, with kinky hair in several pigtails that point in all directions, filthy and torn clothes. She was very mischievous, with no education nor moral instruction.25 Stowe’s Topsy was “one of the blackest of her race; and her round, shining eyes, glittering as glass beads, moved with quick and restless glances over everything in the room.”26 Topsy is further juxtaposed in Uncle Tom’s Cabin with Eva, the archetypal angelic little white girl, who tries to help Topsy.27 Although Stowe’s abolitionist intention was to have her audience sympathize with Topsy by underscoring the neglect children experience under the institution of slavery, Topsy’s character was adopted by minstrel shows and became the archetypal humorous "pickaninny" stereotype which implied that all black children were impoverished.28

The same pickaninny stereotype was perpetuated through dolls of Topsy.29 The most infamous Topsy doll was called “Topsy/Turvy” or “Topsy/Eva.”30 Topsy/Turvy dolls featured two dolls on one body; one side was a well dressed blond-haired white doll meant to be Eva. When flipped upside down, however, the doll would transform into a “grotesque, thick-lipped, wide-eyed, sloppily dressed black doll” meant to be Topsy.31 Topsy dolls were often made of fabric with her skin coloring ranging from medium brown to dark black.32 Overall, contemptible collectibles that appropriate the pickaninny stereotype “rarely depict a clean, well-dressed black child.”33

Fig. 3: Reliable Dolls, Topsy-1316 (c.1930-1940), Composition, Various sizes available from 10 inches to 20 inches, Canadian Museum of History, Quebec, Canada. In Reliable Dolls 1940 Catalogue.

The description of Topsy as the pinnacle pickaninny stereotype further “implicates all blacks.”34 Children are not held responsible for educating and keeping themselves clean; rather this was the responsibilities of their parents.35 Therefore, it was the fault of black parents, both enslaved and free, that their children were uneducated, immoral and dirty.36 The pickaninny stereotype primarily implicates black mothers who are too busy caring for the white children of their masters/employers to care for their own children; this is reflected in the mammy stereotype. 37This enabled white people to justify slavery and treat free blacks as “second-class citizens.”38 However, this “justification” does not address the white-induced economic factors that inhibit black social mobility and contribute to the lack of education and slovenly appearance of black children.39

The mammy stereotype is one of the most popular amongst contemptible collectibles, especially those relegated to the kitchen.40 The mammy caricature was created in the imagination of pro-slavery defenders and gained popularity during the Jim Crow period in America with the emergence of the most known commercial expression of mammy, Aunt Jemima.41 Generally, the mammy caricature posits that black women gain a genuine fulfillment from not raising their own children.42 The mammy is often associated with the kitchen since she cooks for her white family. She poses “no sexual threat to their white mistresses” for she is usually inscribed with masculinized features.43 She is often depicted as overweight, with a big smile and large breasts.44

The mammy of the “Big House” is a stereotype that first emerged to justify slavery by suggesting that black women were content with their enslavement.45 The mammy stereotype also posits that black women are only fit for domestic labour This rationalises the economic discrimination they experienced as both enslaved and free blacks during and after the period of slavery in America and, as I suggest, Canada.46 As such, the occupational stereotypes portrayed through antiblack dolls relates to the largely segregated job-market in American and Canada, as well as reflects the perceptions of white people towards black people after slavery was abolished.47

Fig. 4: Reliable Dolls, Topsy-1316 (c.1930-1940), Composition not original clothing[?], 12 inches, Private Collection, Toronto, Canada.

The mammy stereotype was also adopted in minstrel shows, like Topsy, where white men would transgress race and gender boundaries to entertain their audiences as black women “super mothers”.48 Like Topsy, the mammy stereotype was also used in Stowe’s book through the figure of Aunt Chloe. Aunt Chloe has a “round, black, shiny face [that is] so glossy” and “her whole plump countenance beams with satisfaction and contentment from under a well-starched checked turban” used to hide her “nappy” hair.49 Although she had three children herself, Aunt Chloe does not have time to care for them as much her slaveowner’s children. As such, Aunt Chloe perpetuates the mammy caricature for she “never put her or her family’s needs ahead of those of her white charges,” nor did she want to be free from her position as a surrogate mother to white children.50 In short, mammies are caricatured by running white households as “smiling, self-assured, overweight, born-to-nurture black women.” This deflects from the true relationship between enslaved and free black women and their owners/employers that was largely abusive on several fronts.51

Although the enslavement of black people ended in America with the civil war in 1865 and in Canada in 1833, contemptible collectibles with mammy and pickaninny stereotypes continued to be mass-produced and sold.52 Implicit in each rendition was the notion that mammies were both happy and honored to work for their white employers.53 The stereotype of black mammies as selfless and Topsy as dirty persisted strongly with the creation of both mass-produced and handmade dolls in Canada.

Before analysing the Topsy and Mammy stereotype in Canadian dolls, it is important to contextualize them in relation to Canada’s colonial history. Canada is often celebrated as being a Country without a colonial history that merely helped slaves escape America though the Underground Railroad.54 However, Canada also participated in the Transatlantic Slave trade.55 In fact, Canada had of a slave minority population that functioned under the laws of chattel slavery. Enslaved black men and women were considered movable property; they were commodities to be purchased, sold and inherited.56 Under Le Code Noir, slaveowners could practice corporal punishment and there were specific regulations that prohibited “miscegenation,” which suggests the policing of enslaved women’s sexuality since slavery was a matrilineal institution.57 Ultimately enslaved people had no legal autonomy. Furthermore, since the climate in New France could not sustain plantation slavery, most enslaved people were forced to work as domestic labourers.58 It has been suggested that by 1759 there were 3,604 slaves in New France and at least 1,132 were classified as black, of which only 192 were field labourers.59 Most were owned by the merchant classes since black enslaved people were considered rare and luxury objects.60 Enslaved black women, especially, were considered “particularly fashionable and noteworthy possessions” since there were reportedly more black men then women in Canada.61

Although slavery was abolished in Canada in 1833 under the British Empire, racist attitudes towards free black people continued in the form of minstrelsy and segregation. Blackface minstrel shows were performed in Canada as early as the 1840s by American minstrel companies.62 Localized minstrelsy also emerged in Canada and were popularized from the 1860s to the 1910s, yet there were shows as late as the 1930s in Toronto. Tellingly, this aligns with the date of production of Topsy-1212 by the Reliable Toy Company, also based in Toronto. In fact, one of the most successful minstrel performers was Canadian-born colin burgess, from Toronto..63 Additionally, Hugh Hamall from Montreal founded the La Rue Minstrels in 1867 whose caricatures featured both a mammy and pickaninny sometimes called Topsy.64 The mammy character was “imbued with a “natural” ability to please and serve whites” while Topsy was a “wild, stupid and unkept woolly-headed pickaninny.”65

Just as Canada’s history with blackface and slavery is often erased, so too is evidence of segregation. While Canada may not have Jim Crow laws, segregation did exist and it emerged out of slavery at the same time as minstrel shows. For instance, in Montreal, the Loew’s Windsor Theatre publicly announced in 1919 that black customers would have segregated seating in what they called a “Monkey cage” in the upper balcony of the opera house.66 Canadian school were also segregated and the last segregated school in Ontario was only closed in 1965.67 Additionally, during the 1930s in Ontario, there was a rise in Ku Klux Klan activities since there were no laws prohibiting discrimination anywhere in Canada.68 This also speaks to the structural racism present in occupational structures in twentieth century Ontario. Specifically, there was an over-representation of blacks in low-skill blue-collar occupations from 1881 to 1901 who were being paid less than their white counterparts.69 This discrepancy in wages attests to the boundaries black Canadians faced to attain more skilled jobs.70 Within the same time frame of the early to mid-1900s when minstrelsy and segregation were preformed and practiced, racist attitudes were also present in Canadian dolls through pickaninny and mammy stereotypes.

The pickaninny stereotype was perpetuated through dolls that were mass-produced by the Reliable Toy Company, founded in 1920 in Toronto by two Jewish brothers; Solomon and Alex Samuels.71 In 1935, they became “the largest doll manufacturing organization in Canada and the British Empire,” They described that their dolls are “more beautiful, more lifelike and a better money’s worth each year”.72 The Reliable Toy Company is most known for their plastic technology and production of indigenous and Mountie dolls.73 However, they also produced several types of “Topsy” dolls from the 1940s to the 1960s.74

Fig. 5: Anonymous, Black Female Doll holding White Child (c.1935), Fibre: cotton, velvet, skin: leather, Synthetic: plaster, glass, metal, 34 x 17.2 cm, McCord Museum, Montreal, Canada.

In the 1940 catalogue, Topsy-1212 [fig.1] and Topsy-1316 [fig.3] are both labelled as a “popular negro doll,” likely the age of a baby or toddlers, who wear little dresses and shoes similar to those of the white dolls in the same catalogue [fig,6].75 Though both are named “Topsy,” Topsy-1212 more accurately perpetuates the “pickaninny” stereotype. For example, Topsy-1212 exhibits a very deep, almost black, complexion with the stereotypical pickaninny pigtails pointing in all directs and exaggerated red lips recalling minstrel performances. Additionally, Topsy-1212 has “side-glancing” eyes common in other early twentieth century “Topsy” dolls that is supposed to speak to the mischievous behaviour of “pickaninnies”.76

While the catalogue Topsy-1212 is pictured wearing a neat cotton dress, the Topsy-1212 [fig.2] from the private collector is pictured in a short poorly knitted dress with a comically large button at the center and no shoes. Although the knit dress was likely not the original clothing that Topsy-1212 was sold with, it follows the trope of the “pickaninny” as both unkept and poor.77 Topsy-1212 is also made with gold hoop earrings, a feature that is not present in any of the white dolls from the 1940 catalogue.78 As such, by having Topsy-1212, a doll the age of a toddler, wear jewelry more typically found on dolls of women, the Reliable Toy Company perpetuated the sexualization of black girls. Specifically, oversized hoop earrings on black women were tropes used to present black female bodies as alluring, exotic and overdressed, which are commonly found in Sapphire caricatures.79 Pickaninny stereotypes are steppingstones that allow for the evolution of types; from Topsy to Sapphire. Therefore, like in the period of slavery when girls were sexualized and aged to carry children, so too was Topsy-1212.80

Lastly, it is important to note that although the Reliable Toy Company had hair stations where white dolls had their synthetic hair styled, as seen in the 1940 catalogue, Topsy-1212’s hair was made of plastic. Similarly, Topsy-1316’s hair is covered by a bonnet. This speaks to both the refusal of white manufactures to bother reproducing black hair and the lack of knowledge they had of black hair texture.81 As a solution, they instead covered Topsy-1316’s hair and made Topsy-1212’s pigtails out of plastic. Though Topsy-1316 is of a lighter completion and still pictured in a neat cotton dress by a private collector, she nonetheless has the stereotypical side-glance, red lips and lack of styled hair like Topsy-1212.

The Black Female Doll holding a White Child [fig.5] follows similar tropes but perpetuates the mammy and “Happy Darky” stereotype that is related to black female domesticity during and after the period slavery in Canada.82 The Black Female Doll holding a White Child was gifted to the McCord Museum by Mrs. Samuel T. Adams and was likely handmade in c.1935.83 Samuel T. Adams (1921-1978), a white man, was the Chairman of the McGill Ophthalmology Department in 1971 and a primary donor to the McCord museum.84 He was married to Doreen Muriel Brown (1919-2018), also known as Mrs. Samuel T. Adams, and together they had two daughters, Judi and Jorie.85 Brown also gave the McCord museum three other antiblack dolls that each portray the mammy stereotype; two from c. 1935 and one from the late 19th century.86

Fig. 6: Reliable Dolls, Chuckles-11166 (c.1930-1940), Composition, Various sizes available from 14 inches to 20 inches, Canadian Museum of History, Quebec, Canada. In Reliable Dolls 1940 Catalogue.

The Black Female Doll holding a White Child exhibits “inky” and extremely dark skin, made of leather,87 and wide almost googly-eyes that evoke distasteful characterises used to caricature black people in minstrel shows. This serves to “emphasize the assumed beauty of the white baby” that she is holding.88 The use of leather skin speaks to the common equation of black people with animals and further exhibits the “shinny” and “glossy” face used to describe Aunt Chloe. As such, the use of blackface characteristics and leather skin arguably was done deliberately by the maker to distort and degrade black women.89 Additionally, the black woman wears a long loosely fitted blue dress, made of cotton and velvet, with a white apron to reference her occupation as a domestic labourer. The loose dress presents the doll with large breasts that further perpetuates the overweight mammy stereotype discussed above. Similarly, the inclusion of the white baby wrapped in a lace blanket underscores that “black women continued to raise white children and care for white adults well after the end of slavery.”90 As such, Black Female Doll holding a White Child assumes the role of the mammy caricature, which implied that black women were only fit to be domestic workers and were content caring for their owner’s/employer’s white children.91

The Black Female Doll holding a White Child thus reinforces the racist ideology of “white ownership, surveillance, regulation and control over black (female) bodies” that emerged from the period of slavery and continues to exist.92 The notion of white ownership is also perpetuated through these dolls since they were likely used by white children, likely Brown’s daughter’s Judi and Jorie.93 As such, dolls of this nature likely circulated between white Canadian homes, assuming different and complex meanings in their social lives, before ending up in the McCord Museum.

The Black Female Doll holding a White Child is also wearing a multicolored headwrap that, like Topsy-1316, covers any evidence of her hair. However, the headwrap also speaks to the processes of creolization that occurred in Canada during the period of slavery.94 It is pertinent to note that creolization, the coming together of European, Indigenous and African cultures and traditions, always happens under duress for enslaved black people and affects clothing, language and religion.95 Headwrapping survived the Middle Passage and entailed a mixing of aesthetic traditions in both imperial states and their colonies.96 It served utilitarian functions, like protection from sun, keeping hair clean, hiding unkept hair, helping preserve braids, or concealing scars and country marks. Additionally, headwrapping was an alternative means of self-adornment and aesthetic display, since enslaved men and women did not always have time and tools to do their hair.97 Besides being a source of resistance and self-fashioning since cultural preservation was hard work, headwrapping was a communal practice that functioned as a language to tell details about class, marital status, labor, ethnicity, and occupation.98 Therefore, the orange, purple and cream-colored headwrap that the doll is wearing becomes “a proud source of beautification, identification, cultural continuity and communication” of an African heritage in Canada where there was a slave minority population. 99 However, this meaning was likely overlooked by white manufactures who, like with Topsy-1316, strategically used headwraps to cover the doll’s hair. This was another sign of ignorance towards black hair and the refusal of white manufacturer to the produce dolls with black hair styles and textures.

Lastly, like Topsy-1212, Black Female Doll holding a White Child is also featured with jewelry. Specifically, the Black Female Doll holding a White Child is wearing silver hoop earrings and a turquoise beaded necklace. Within the context of Topsy-1212, the use of jewelry was suggested to sexualize black girls. The relation between jewelry and the sexualization of black children can be further extended to address sexual exploitation with regards to black women in Black Female Doll holding a White Child.100 Therefore, the jewelry worn by this mammy stereotyped doll, who likely did not have the means to purchase it herself as a domestic servant, may have been a form of payment for sexual favors by their white owners/employers.101 Overall, both Topsy-1212 and Black Female Doll holding White Child are “othered” against the ideal white body to conform to “the hierarchal and marginalizing trajectories of colonization”.102

Considering that these dolls were sold for $1.56 to $2.56 in the 1940s and that black Canadian’s were paid significantly less than their white counterparts, it is most probably that they were marketed towards white people not black people. 103 Likewise, black parents likely did not purchase or make antiblack minstrel type dolls for their children, which would serve to rationalize their oppression.104 Furthermore, a study in 1939 America shows that children, regardless of their own race, overwhelmingly selected white dolls over black dolls.105 The selection of the white doll over the black doll by black children suggests the unsettling practice of “racial self-loathing” since dolls operate as devices for identify formation. Likewise, it anticipates the likely prospect of black girls’ futures as caregiver to white children; the same can be said for black children playing Black Female Doll holding a White Child.106 Furthermore, the deliberate naming of the black female dolls by the Reliable Toy Company as “Topsy” purposefully reinforces and sustains negative perceptions of black females through child play.107 Therefore, by giving physical reality to racist ideologies in the form of dolls that emphasize the “otherness” of black females, Canadian doll makers justify segregation. Dolls thus serve as “cultural indoctrination instruments” in racial stereotyping.108

The analysis of “mammy” and “Topsy” stereotypes in twentieth century Canadian dolls, exposes the legacy of the exoticization of the black female body as racial “other.”109 Specifically, the representation of black females in the form of different caricatured dolls made by white Canadians, reveals the obsessive need to systematically create typologies for black bodies; such as “pickaninnies” and “mammies.”110 However, the stereotypes reflected in black female dolls are imagined by Canadians who “deposited their desires and fears” against black people.111 By studying Topsy-1212 and Black Female Doll holding White Child, I was able to establish connections between distorted depictions of black Canadian females, the treatment they received during and after slavery, and the complexity of race relations in Canada during the period of minstrelsy and segregation. In conclusion, we have seen that Topsy-1212 and Black Female Doll holding White Child appropriated pickaninny and mammy stereotypes, which in turn destabilize Canada’s collective identity as tolerant and inclusive. Just as slavery, minstrelsy and segregation existed in Canada, so too does “black Canadiana memorabilia” that speaks to the nation’s racist past.

Endnotes

1. “Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia,” Ferries State University, (date of last access 1 December 2019) https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/caricature/homepage.htm

2. “Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia,” (date of last access 1 December 2019)

3. Patricia A. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies: Black Images and Their Influence on Culture, (New York: Anchor Books, 1994), p. 11.

4. Camille A. Nelson, and Charmaine A. Nelson eds., “Introduction,” Racism Eh?: A Critical Inter-Disciplinary Anthology of Race and Racism in Canada (Concord, Ontario: Captus Press/Captus University Publications, 2004), pp. 2-3. And Eva Mackey, “Introduction: Unsettling Differences: Origins, Methods, Frameworks,” The House of Difference: Cultural Politics and National Identity in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002), pp. 1-2.

5. Nelson and Nelson, “Introduction,” p. 3.

6. Nelson and Nelson, “Introduction,” p. 3.

7. Alexandra Kelebay “ ‘History Could be Taught by Means of Dolls…,’:Race, Doll-Play, and the History of Black Female Slavery in Canada,” Towards an African Canadian Art History: Art, Memory, and Resistance, eds. Charmain Nelson (Concord, Ontario: Captus Press, October 2018), p. 94.

8. Nelson and Nelson, “Introduction,” p.3.

9. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.5.

10. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, pp.7 & 11.

11. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.12.

12. Some examples include cookie jars, slat and pepper shakers, postcards, lawn posts, dolls, masks and other toys. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.7.

13. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.7.

14. Kenneth W. Goings, Mammy and Uncle Mose: Black Collectibles and American Stereotyping, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), p. xii.

15. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.7. And Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia,” , (date of last access 1 December 2019)

16. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.11.

17. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.11.

18. Goings, Mammy and Uncle Mose, pp. xii, xix, & 1.

19. See for example the advertisement by Fairbank's Soaps that uses images of two “Gold Dust Twins”. This coincided with and implementation of Jim Crow segregation practices in America. Erica Morassutti, “Scrubbing Doubles: The Gold Dust Twins and Racial Tropes in Nineteenth-Century American Soap Ads,” Chrysalis, vol.1 no. 7 (2019), pp. 27-38. And Goings, Mammy and Uncle Mose, pp. xii, xix, & 1.

20. Goings, Mammy and Uncle Mose, p. 27.

21. Liz Conor, “The ‘piccaninny’: Racialized Childhood, Disinheritance, Acquisition and Child Beauty,” Postcolonial Studies vol. 15, no. 1 (March 2012), p. 47.

22. Though the term pickaninny was also used to describe indigenous children. Conor, “The ‘piccaninny,’” p.47.

23. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.13.

24. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.13.

25. David Pilgrim, and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Understanding Jim Crow: Using Racist Memorabilia to Teach Tolerance and Promote Social Justice, (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2015), pp. 90-3.

26. Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom's Cabin (London: J. Cassell, 1852), p. 243.

27. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.13.

28. In minstrel shows, Topsy was reinvented as a source of humor through her broken English, devilish habits and poor appearance. Pilgrim, Understanding Jim Crow, p.93.

29. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.14.

30. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.14.

31. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.14.

32. The pickaninny stereotype was further present in other artifacts such as in advertisements, like the Topsy Chocolate Honey Dairy Drink, on postcards eating watermelon or being attacked by alligators, and even on decorative plates. Similarly, some pickaninny caricatures are also presented as naked as a sign of both neglect, abuse and sexualization. Pilgrim, Understanding Jim Crow, p.93.

33. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.15.

34. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.16.

35. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.16.

36. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.16.

37. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.16.

38. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.16.

39. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.16.

40. Most notably in the form of cookie jars.

41. Pilgrim, Understanding Jim Crow, p.70.

42. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.25.

43. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.25. And Goings, Mammy and Uncle Mose, p. xxi.

44. Goings, Mammy and Uncle Mose, p.43. And Pilgrim, Understanding Jim Crow, p.61.

45. Goings, Mammy and Uncle Mose, p.43. And Pilgrim, Understanding Jim Crow, p.61.

46. Pilgrim, Understanding Jim Crow, p.64.

47. Pilgrim, Understanding Jim Crow, p.64.

48. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, pp.44-5.

49. Stowe, Uncle Tom's Cabin, p.31.

50. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.47. And Pilgrim, Understanding Jim Crow, p.67.

51. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.47.

52. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.51.

53. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.51. And Pilgrim, Understanding Jim Crow, p.61.

54. Nelson and Nelson, “Introduction,” p. 3.

55. Nelson and Nelson, “Introduction,” p. 3.

56. This form of isolation from other enslaved people in Canada is also a source of trauma. Charmaine A. Nelson, “Slavery, Portraiture, and the Colonial Limits of Canadian Art History,” Representing the Black Female Subject in Western Art (New York: Routledge, 2010), p. 68.

57. To what extent was this regulation practiced is contradictory due to the presence of many mixed-race enslaved people in Canada. Nelson, “Slavery, Portraiture, and the Colonial Limits,” pp. 68-9.

58. Nelson, “Slavery, Portraiture, and the Colonial Limits,” pp. 68-9.

59. This likely justifies the life expectancy of black slaves in Canada at 25.2 whereas indigenous slaves lived until 17.7 likely due to harsh field labour. Nelson, “Slavery, Portraiture, and the Colonial Limits,” pp. 69-70.

60. For example, a black enslaved person would be sold for 900 livres whereas an indigenous enslaved person would be sold for 400 livres. Nelson, “Slavery, Portraiture, and the Colonial Limits,” p.70.

61. Nelson, “Slavery, Portraiture, and the Colonial Limits,” p.70.

62. Evidence suggests that there was substantial resistance by black Torontonians to American minstrel shows in 1840 though they were not successful in banning them. Cheryl Thompson, “ ‘Come One, Come All,’: Blackface Minstrelsy as a Canadian Tradition and Early Form of Popular Culture” Towards an African Canadian Art History: Art, Memory, and Resistance, eds. Charmain Nelson (Concord, Ontario: Captus Press, October 2018), pp.98-9.

63. Thompson, “Blackface Minstrelsy,” p.101.

64. Thompson, “Blackface Minstrelsy,” p.101.

65. Thompson, “Blackface Minstrelsy,” p.108.

66. Natasha L. Henry, "Racial Segregation of Black People in Canada,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, (date of last access 5 November 2019) https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/racial-segregation-of-black-people-in-canada.

67. James Walker, “Racial Discrimination in Canada: The Black Experience.” Historical Booklet / Canadian Historical Association, (Ottawa: Canadian Historical Association, 1985), p.14.

68. Constance Backhouse, Colour-Coded: A Legal History of Racism in Canada, 1900-1950 (Toronto: Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History by University of Toronto Press, 1999), p. 197.

69. Colin McFarquhar, “The Black Occupational Structure in Late-Nineteenth-Century Ontario,” Racism Eh?: A Critical Inter-Disciplinary Anthology of Race and Racism in Canada, eds. Camille A. Nelson and Charmaine A. Nelson (Concord, Ontario: Captus Press/Captus University Publications, 2004), pp. 50-60.

70. McFarquhar, “The Black Occupational Structure,”, p.60. And Charmaine A. Nelson, “Racing Childhood Representations of Black Girls in Canadian Art,” Representing the Black Female Subject in Western Art (New York: Routledge, 2010), p. 52.

71. At the beginning, the Reliable Toy Company depended on imported doll parts from Germany and America, but from 1922 until their closing in 1995, they began to produce their own doll parts. “Reliable Toy Company,” Canadian Museum of History, (date of last access 1 December 2019) https://www.historymuseum.ca/canadaplay/manufacturers/reliable-toys.php

72. “Reliable Toy Company,” Canadian Museum of History, (date of last access 1 December 2019)

73. “Reliable Toy Company,” Canadian Museum of History, (date of last access 1 December 2019)

74. “Reliable Dolls made in Canada Catalogue (1940), Canadian Museum of History, Quebec (date of last access 1 December 2019) https://www.historymuseum.ca/canadaplay/introduction/catalogues.php

75. In later1950 renditions, Topsy type dolls made by the Reliable Toy Company are described as “a lovable pickaninny,” “little chocolate colored cutie” and “a brown bundle of fun”. Reliable Dolls made in Canada Catalogue (1940), Canadian Museum of History, Quebec (date of last access 1 December 2019)

76. See examples of other side-glancing Topsy dolls in Debbie Behan Garrett, Black Dolls: A Comprehensive Guide to Celebrating, Collecting, and Experiencing the Passion, (Dallas, TX: Debbie Behan Garrett, 2008), pp. 32-70.

77. The lack of shoes suggests that Topsy’s parents were too poor to purchase any. Blair McFadden, “The ‘Piccaninny Type’: Reproducing Colonial Discourse, Black Children as Subjects in Canadian Painting,” Chrysalis, vol.1 no. 1 (2014), p.45.

78. Reliable Dolls made in Canada Catalogue (1940), Canadian Museum of History, Quebec (date of last access 1 December 2019)

79. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, p.47. And “Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia” Ferries State University, (date of last access 1 December 2019) https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/caricature/homepage.htm

80. McFadden, “The ‘Piccaninny Type’,” p.48.

81. Shane White and Graham White, “Slave Hair and African American Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” The Journal of Southern History, vol. 61, no. 1 (February 1995), p.69.

82. Kelebay “Race, Doll-Play,” p. 90. And Goings, Mammy and Uncle Mose, p. 66.

83. “The Museum System – CAD Fact Sheet,” McCord Museum, November 12, 2019. Email.

84. Sean B Murphy, Portraits of Ophthalmology at McGill University, 1876-1990. Montreal: n.p. 201?.

85. Brown also went to McGill University. “Marriage: Adams-Browns” Le Canada Français (Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu), issue 74, Thursday, 12 August, 1943, p. 16. And “Doreen Adams Obituary,” (2018) Montreal Gazette (date of last access 1 December 2019) https://montrealgazette.remembering.ca/obituary/doreen-adams-1070644794

86. “The Museum System – CAD Fact Sheet,” McCord Museum, November 12, 2019. Email.

87. Kelebay “Race, Doll-Play,” p. 90.

88. Kelebay “Race, Doll-Play,” p. 90.

89. Turner, Ceramic Uncles & Celluloid Mammies, 14. And Kelebay “Race, Doll-Play,” p. 90.

90. Evidence that black women continued to raise white children and care for white adults well after the end of slavery in Canada is found through photographs like Wm. Notman and Son, Baby Paikert and Nurse, Montreal, QC, 1901.

91. Laura Green, “Stereotypes: Negative Racial Stereotypes and Their Effect on Attitudes Toward African-Americans,” Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, (date of last access 1 December 2019) https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/links/essays/vcu.htm

92. Kelebay “Race, Doll-Play,” p. 83.

93. Kelebay “Race, Doll-Play” p. 90.

94. Kelebay “Race, Doll-Play,” pp. 90-2.

95. White and White, “Slave Hair and African American Culture,” p. 71.

96. White and White, “Slave Hair and African American Culture,” p. 71.

97. Their only day of rest would have been on Sundays, which was likely a day used to practice self-care. White and White, “Slave Hair and African American Culture,” p. 71.

98. White and White, “Slave Hair and African American Culture,” p. 71.

99. It is also important to think about who would help enslaved women wrap their heads in Canada since there was a slave minority population. Similarly, it is important to note how memory and resistance intersect since enslaved people lost the why in the oppressive system of slavery and only know how to preform these practices. Kelebay “Race, Doll-Play,” 90-2.

100. Kelebay “Race, Doll-Play” p. 91.

101. However, it is possible that black domestic servants did purchase their own jewelry. Kelebay “Race, Doll-Play” p. 91.

102. McFadden, “The ‘Piccaninny Type’,” p.48.

103. Today, Topsy dolls made by the Reliable Dolls Company are sold for $50-$100. Reliable Dolls made in Canada Catalogue (1940), Canadian Museum of History, Quebec (date of last access 1 December 2019). And “Canada Inflation Calculator,” CPI Inflation Calculator, (date of last access 1 December 2019) https://www.in2013dollars.com/1960-CAD-in-1940?amount=2.98

104. Kelebay “Race, Doll-Play” p. 90.

105. Maggie MacNevin, and Rachel Berman, "The Black Baby Doll Doesn’t Fit the Disconnect between Early Childhood Diversity Policy, Early Childhood Educator Practice, and Children’s Play,” Early Child Development and Care, vol. 187, no. 5-6 (2017), p. 832. An example of a visual representation of a black girl playing with a white doll is found in Dorothy Stevens, Amy (c. 1930).

106. McFadden, “The ‘Piccaninny Type’,” p.45. And Nelson, “Racing Childhood,” p. 58.

107. Doris Y. Wilkinson, “The Doll Exhibit: A Psycho-Cultural Analysis of Black Female Role Stereotypes,” The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 21, no. 2 (Fall 1987), p. 25.

108. Wilkinson, “The Doll Exhibit,” p. 26. And McFadden, “The ‘Piccaninny Type’,” p.45. Goings, Mammy and Uncle Mose, p.43

109. Nelson, ed., “Introduction,” p. 5.

110. McFadden, “The ‘Piccaninny Type’,” p.50.

111. Carolyn Dean, “Boys and Girls and “Boys”: Popular Depictions of African‐American Children and Childlike Adults in the United States, 1850–1930,” Journal of American & Comparative Cultures, vol. 23, (2000) p.31.

![Fig. 2: Reliable Dolls, Topsy-1212 (c.1930-1940), Composition not original clothing[?], 17 inches, Private Collection, Toronto, Canada. ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e37a526bbe3b87b370bb999/1582126935910-CESGXJGW76M7HN42BVKO/dolls_2)

![Fig. 4: Reliable Dolls, Topsy-1316 (c.1930-1940), Composition not original clothing[?], 12 inches, Private Collection, Toronto, Canada. ](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e37a526bbe3b87b370bb999/1582127092257-JWOVT0C7AU0R5MNJAPDX/dolls_4)