Aldo Rossi: Echoing Life in the Architecture of Death

Written by Liliane Bamdadian

Edited by Madeleine Mitchell

Preface: The Modena Cemetery of San Cataldo and a Perfectly Timed Collision

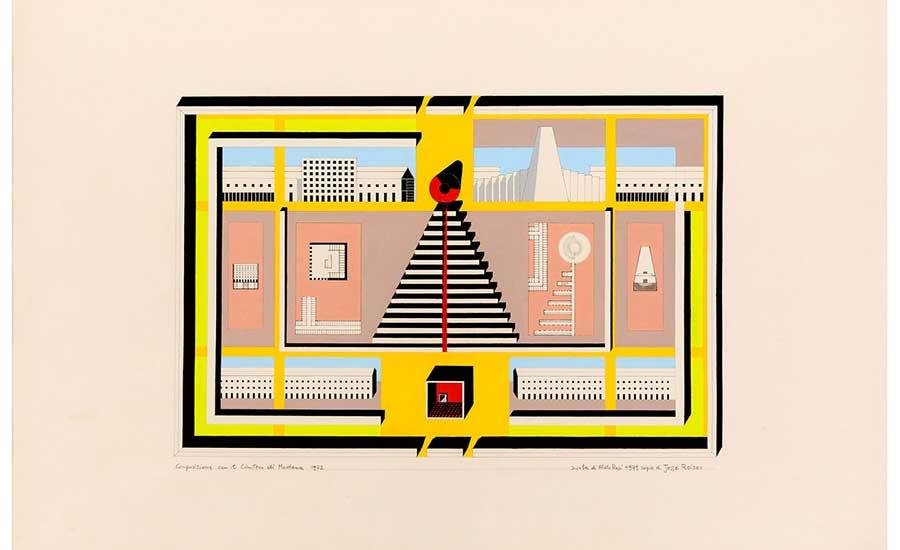

In 1979, Jesse Reiser, a third-year architecture student at Cooper Union met Italian architect Aldo Rossi. Rossi was in New York at the time in aims to establish his own school of architecture, and visited Cooper Union to teach there temporarily (1). Reiser was captivated by World War II airplane models and had himself produced miniature versions of the aircrafts, carefully painted to a machined precision (2). As Rossi entered the third-years’ studio, he was astonished by the models laying on the Reiser’s desk, showcasing the talent behind the punctiliously applied colors on the metal (3). Impressed by Reiser’s meticulous painting technique, Rossi decided to bring the student along with him to Italy to make one of his greatest works transcend the national barrier (4). He commissioned Reiser to reproduce one of his drawings of the Modena Cemetery in San Cataldo, Italy, using carefully selected gouache tones reminiscent of pop art, which contrasted with the architect’s conventional palette that ranged in terracotta-like colours (5). Despite Reiser’s skepticism towards Rossi’s verdict, in regards to the intentions of the architect, the reproduced drawing had a successful rendition (Fig. 1) and introduced an Americanised Rossi to the architectural world, transporting his renowned project past the borders of Italy (6,7).

Figure 1: Painting of Modena Cemetery in Plan. Medium: Gouache. Signed “School of Aldo Rossi, drawn by Jesse Reiser”.

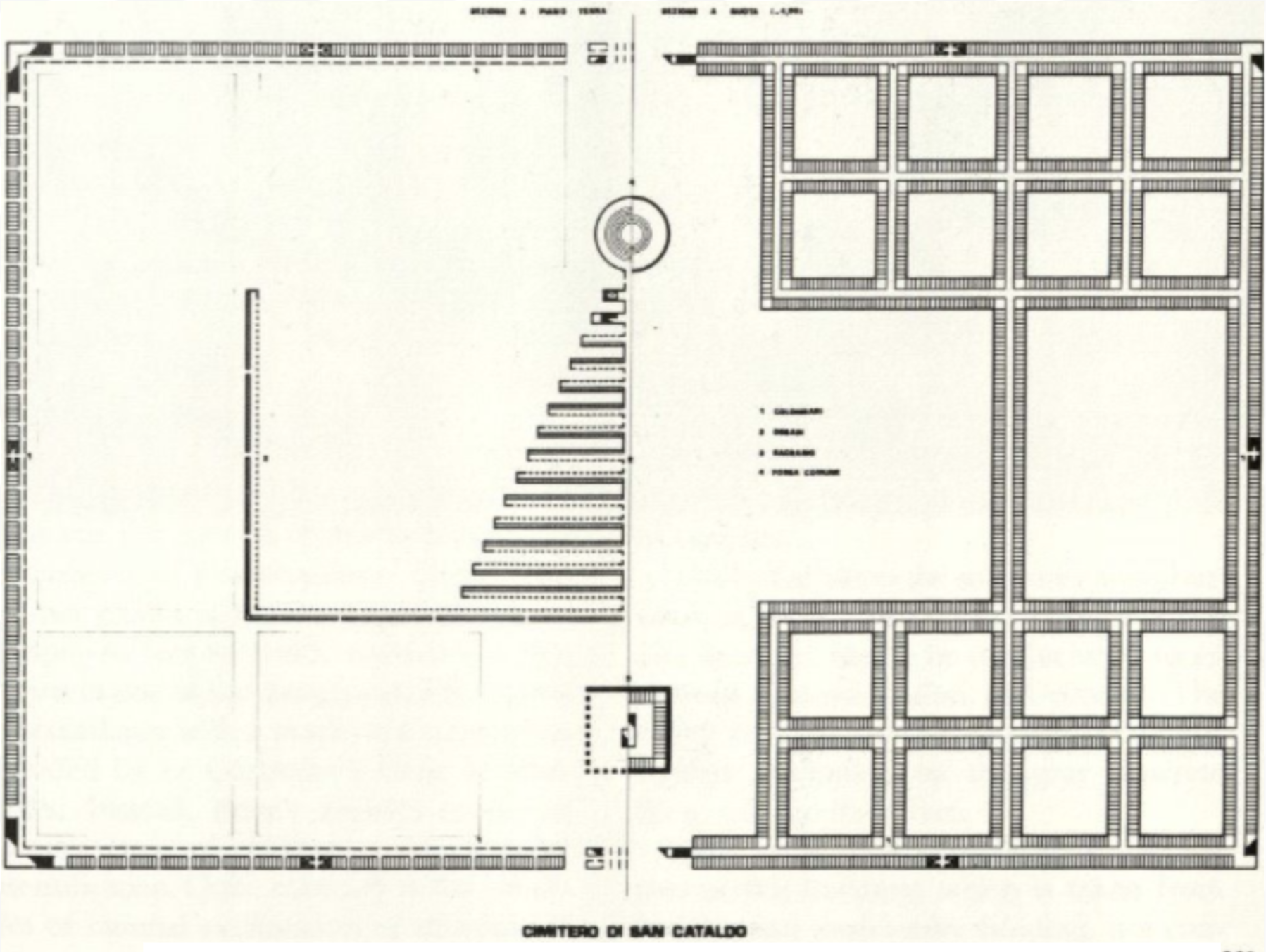

Despite the pop art tones in Reiser’s version of the plan, the Modena Cemetery features blue steel and deep red terracotta (Fig.2), which would be utterly rejected by orthodox modernism’s preference for less flamboyant colour (8). In fact, the cemetery is classified as postmodern for its choice of eccentric colour, bold form and historical allusions (9). Also, the cemetery is not entirely designed by Rossi. A national competition was announced in 1971 and Rossi’s contribution was an addition to the already-existing neoclassical cemetery by Cesare Costa and the Jewish cemetery (10). It appears visually uncomplicated, a typical characteristic of Rossi’s works. From a young age, Rossi drew domestic objects regularly (Fig. 3) and since developed the skill of visualizing buildings as independent forms, much like objects (11). This ability served as the foundation of his instinctive simplicity in design which can be described as an “abstraction in pure forms” (12). In other words, his works are not rich in visual detail, but in meaning and content. Needless to say, his Modena Cemetery design is highly reflective of this philosophy. First, the cemetery is built on a terrain in the shape of two adjacent squares (Fig.4), where their contacting edge forms a path and serves as an axis for the plan (13, 14). On each end of this axis stands a straightforward geometric shape: a cube is erected at the base while a truncated cone stands at the tip of a triangular arrangement of horizontal rows of tombs, where the height of the triangle is voided for the path (15). The last horizontal row, at the base, is extended to enclose the rows of burial chambers, forming a triangle in plan but also in section (Fig.5) (16,17).

Figure 2: Modena Cemetery, San Cataldo, Italy.

Figure 3: Archittetura domestica, Aldo Rossi. Ink, ballpoint and felt pen, varnished.

Figure 4: Floor plan of the whole, divided in two

Figure 5: Perspective and section displaying the perimeter wall, the ossuary, the truncated cone and the rows of tombs.

Moreover, the old perimeter wall was extended to allow the connection between the old cemetery and Rossi’s addition (18). Inside and beneath the cone is a mass grave. The colossal hollow cube serves as an ossuary, a room dedicated to storing the bones of the dead, and memorial to the war dead (19). By merely looking, one might protest that Rossi’s architecture is unsatisfyingly elementary, like an assortment of simple toys on a flat surface, but the most captivating quality of his work is masked within the layers of its meaning. As the Pritzker Prize jury described, it is “ at once bold and ordinary, original without being novel, refreshingly simple in appearance but extremely complex in content and meaning” (20). Thus, his art is read, not only with eyes, but with thought, knowledge and reflection.

Intro: The Architecture of Death

It is instinctive to associate architecture with daily life, for it is an environment that is physically occupied everyday, and so architecture is attributed meanings that enable comfort such as safety, familiarity, intimacy, etc. Architecture also accommodates human forms in the after life, through cemeteries and so its aim is not only to design spaces for living, but also spaces for the dead. This dimension of architecture may seem unobvious, mainly because one does not think of the experience of a corpse inside a tomb. Since experience is associated with living, and living with experience, why imagine oneself in a position where architecture cannot even be experienced, if one cannot imagine not living? Living is commonly understood as an action, but, although there may be a lapse between one’s last breathings and the final instant of life, “dying” is not an action, really, at least not a constant one when compared to living, which is an important distinction in rhythm. It is as if life were a song made of unceasing series of notes in a particular rhythm, and then death is an abrupt rest. If more notes follow, that can only be answered by faith. Many questions may arise from this reflection. For instance, what knowledge allows a living human to design architecture for the non-living? Is the architecture of cemeteries based on the experience of the living visiting the dead? Indeed, much reflection is brought to mind, which highlights only a foretaste of the challenges that architects who design such spaces confront. The Modena Cemetery, for instance, is renowned as one of Rossi’s greatest works, as it acknowledges many requirements that he,, deemed worthy of meeting (21). Considering the obvious fact that, in order to design, one must have knowledge, and cemeteries are thus designed based on accumulated wisdom, then cemeteries are inevitably related to life. Italian funerary architecture, specifically Rossi’s cemetery, is a well-suited example of this claim. Thus, one can assert that Rossi’s Modena Cemetery is a reflection of the living. In fact, many of Rossi’s considerations for its design rely on the knowledge of the living: memory, hierarchy, etc. He himself referred to his creation as “The City of the Dead”, where “city” evidently relates to life once more, because without the living, cities could not physically exist: they would look abandoned, like ruins (22). Thus, the city has a soul created through the energy brought by its citizens.

Figure 6: Example of upper-class tombstone in Stone Mountain Cemetery during the industrial period.

Architecture of Death Mirroring Social Status and Urban Living

Following the secularization of funerary traditions and the era of hierarchical demarcation under modernist values, Western, as well as Italian cemeteries began to adopt egalitarian morals, especially under postmodernism’s influence (23). Instead of ostentatious tombstones that communicate power and superiority through scale, material and spatial arrangement (Fig. 6) , the philosophy of equality regardless of social class, gender, religion, etc., became the guiding awareness that led to a funeral architecture of equality (24, 25). In Italy, Modena was the first to apply these egalitarian principles in funerary practices, where the Cemetery of the Three Hundred and Sixty-Six Graves by Ferdinando Fuga was entirely devoted to house the corpses of the poor (26). Similarly, Rossi’s Modena Cemetery also displays egalitarianism in its architecture. In the spatial arrangement of the ossuary, for example, any distinction between class is prevented by organising corpses into a massive cube, where openings punctuating the simple structure, similar to warehouse storage, serve as spaces for the dead, which negates hierarchy through an objective approach (Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10). His design thus utterly rejects the modernist dogma enacted by Louis Sullivan “form follows function”, as the function of the cemetery is completely unrelated to its industrial, factory-like visual impression (27, 28, 29, 30). In fact, Rossi was opposed to modernist architecture for its monotony, and association with the recent trauma of fascism Instead, he adopts a historicist approach by grounding the function of his design on nostalgia: he aims to evoke the feeling one has in the urban fabric of Modena through an abstract reduction of forms to forge a city for the dead inspired by urban space for the living (31, 32, 33).

Figure 7: Close up view of the square openings in the ossuary.

Figure 8: Display of the storage area of a warehouse, similar to that of the ossuary (fig.7).

Figure 9: View of the ossuary as a grand open space.

Figure 10: Display of the storage area of a warehouse, similar to that of the ossuary (Fig. 9).

In Aldo Rossi and the Spirit of Architecture, Diane Ghirardo explains how the cemetery’s design is founded on urban life in Modena, but also how it is reformed to be implemented as a memory in the funerary architecture:

Crowds throng the piazzas and public buildings of an Italian city such as Modena most of the day, crisscrossing the city in cars, buses, motorcycles, and bicycles. They are noisy, bustling, chaotic and full of life. Rossi’s Modena Cemetery is everything that the city is not: hushed, it has no crowds, there are no vehicles of any sort…The cemetery buildings may resemble others found in the city, but only on the level of form, dignified, even grand. Absence, then, is the most salient characteristic of Rossi’s cemetery. (172)

As the above quote substantiates, absence relates to the aforementioned metaphor, concerning rhythm and silence, where the abrupt rest, or emptiness rather, subsequent to a lively rhythm, the city, symbolizes death. Thus, the use of the features that characterize the memory of an empty space designed for living, the city, as an inspiration to an architecture designated for the dead establishes a feeling of nostalgia and evidences the association of the living, and the architecture of the living, with Rossi’s funerary architecture. Likewise, the eradication of hierarchy privileging the dead through egalitarian architecture reinforces the assertion of cemeteries influenced by the living, as their transitioning ideologies consequently shaped Rossi’s housing of the dead.

Anthropomorphic Poetry in Rossian Design

Interestingly, the renowned Modena Cemetery by Rossi is a metaphor of the human itself. The language in the shapes of the structures erected in the “City of the Dead” exhales a lexicon related to the human bone structure: spine, ribs, bare bones, etc. But why bones? Perhaps because after death, what remains in the living world are one’s bones. Analogously, after the experience of reality, what remains of what was experienced through the senses is the memory of it. Hence, bones symbolize the memory of the reality prior to death, that is, life. Ironically, at the time when Rossi was designing the Modena Cemetery, he was in a hospital bed in Croatia with fatal injuries following a car accident and visualized the cemetery through his body’s wounds (34). In other words, he was near death while inventing an architecture for the dead, and thus sought inspiration from himself. Despite the pain, Rossi seemed to oddly, but creatively, benefit from the experience: “I saw the skeletal structure of the body as a series of fractured parts to be reassembled” (35). This statement suits the description of his cemetery in plan, which consists of simple solids, or fragments, that are distanced on the same central axis, intersected by paths and courtyards perpendicularly, in the same way bones are axes arranged around a central spine. Another interesting study of the cemetery’s plan is portrayed in a sketch by Rossi (Fig.11), where the design is claimed to be reminiscent of a fish skeleton (36, 37). Rossi also pictured the human body, as a whole in his creation, saying that his design resembled “an inert body sprawled on the ground, like the Deposition of Christ from the cross”. As the distinction between human and architecture lessened, the meaning of architecture increased (38). Hence, his ideas radiate an appreciation of the function of the architecture, but the function is expressed in the meaning and not the form, which confirms the prior assertion on his rejection of modernism’s function-derived strategy in architectural design. Lastly, the ossuary stands as a metaphorical house with no floor or ceiling, thus a house on its bare bones, the walls, since they are the only structural element still holding the house as a piece (39). The “City of the Dead” is again portrayed using a skeletal language in its meaning to connect the architecture with its function. In spite of the factory-looking architecture, the analysis of the structures he designed prove that his ideas emerged from an anthropomorphic perspective, as he was himself an inspiration to his imaginative mind. Thus, Rossi envisioned an architecture of the dead through bones, the physical element that is everlastingly shared between both dead and living which also recall the theme of memory, not only of the urban life, but also of the anatomy of the living: Rossi’s architecture of the dead is once more interrelated with the living.

Figure 11: Sketch of the plan juxtaposed with skeleton of a fish.

Conclusion

To conclude, Rossi’s funerary architecture mirrors the living in many ways, namely by disallowing the discrimination of the dead in funerary architecture based on their living social status, which substantiates a denial of the modernist approach and an acceptance of the postmodern ideals which prevailed at the time. Thus, his architecture for the dead is conscious of the fluctuation of social values established by the living. Also, by rooting his intention for the design of the cemetery in the memories of the experience of Modena’s urban fabric, Rossi reminds the living of their own city, but implements a feeling of emptiness and cessation to create nostalgia. Unoccupied courtyards and large inhabited spaces imitating the Italian city’s shapes embody a deserted city in which an end has already been reached: a metaphor of death itself. Finally, Rossi also expresses the human anatomy and its bone structure in significant architectural shapes to enhance the very meaning of his architecture for the dead. By imaging the sensations of his fractured body in the plan of the cemetery and reducing all forms to the simplest constituents, the “bare bones”, he communicates the life and death. The connections he establishes between his architecture for the dead and the living are not discernible if one does not take the time to analyze it in depth. Like poetry, Rossi’s architecture is crowded with allusions and rhythm. If one only reads the words and not the meaning, then it becomes a one-dimensional, distant and opaque conception. Once consciousness and wisdom penetrate the layers of his creation, the beauty within it will bloom.

Bibliography

CCAchannel. YouTube. January 17, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MopecAeYSXc.

Collier, C. D. Abby. "Tradition, Modernity, and Postmodernity in Symbolism of Death." The Sociological Quarterly 44, no. 4 (2003): 735. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2003.tb00533.x.

Ferlenga, Alberto. Aldo Rossi, Architecture, 1959-1987. Milan: Electa Moniteur, 1988

Ferlenga, Alberto, and Aldo Rossi. Aldo Rossi: The Life and Works of an Architect. Cologne: Könemann, 2001.

Ghirardo, Diane. Aldo Rossi and the Spirit of Architecture Yale University Press, 2019

Goldberger, Paul. "Architecture View; Aldo Rossi: Sentiment For The Unsentimental." New York Times, Apr 22, 1990, Late Edition (East Coast). https://proxy.library.mcgill.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/427614553?accountid=12339.

Lopez, T. M. (2017). The future city. Southwest Review, 102(1), 101,151. Retrieved from https://proxy.library.mcgill.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1890523429?accountid=12339

Mairs, Jessica. "Postmodernism in Architecture: San Cataldo Cemetery by Aldo Rossi." Dezeen. August 10, 2015. https://www.dezeen.com/2015/07/30/san-cataldo-cemetery-modena-italy-aldo-rossi-postmodernism/.

Malone, Hannah. Architecture, Death And Nationhood: Monumental Cemeteries of Nineteenth-century Italy. (Routledge, 2018), 14.

Reiser, Jesse. "The Story Behind a Drawing: Jesse Reiser on Aldo Rossi." Architectural Record RSS. February 26, 2019.https://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/13936-the-story-behind-a-drawing-jesse-reiser-on-aldo-rossi.

"San Cataldo Cemetery in Modena, Italy." Act of Traveling. https://www.actoftraveling.com/portfolio/san-cataldo-cemetery-modena-italy/.

Storeganizer. "Solutions for Warehouse Storage." Storeganizer. https://www.storeganizer.com/us/solutions/.

"Warehousing & Storage." Warehousing and Storage | Crown International Pack and Move. http://crownintpackers.com/warehousing-storage.html.

Endnotes

1. CCAchannel.YouTube. January 17, 2019. Accessed March 25, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MopecAeYSXc.

2. CCAchannel.

3. CCAchannel.

4. CCAchannel.

5. CCAchannel.

6. Reiser, Jesse. "The Story Behind a Drawing: Jesse Reiser on Aldo Rossi." Architectural Record RSS. February 26, 2019. Accessed March 26, 2019. https://www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/13936-the-story-behind-a-drawing-jesse-reiser-on-aldo-rossi.

7. Reiser, Jesse. "The Story Behind a Drawing”

8. Ferlenga, Alberto, and Aldo Rossi. Aldo Rossi: The Life and Works of an Architect. Cologne: Könemann, 2001.

9. Mairs, Jessica. “Postmodernism in Architecture: San Cataldo Cemetery by Aldo Rossi.” Dezeen. Dezeen, August 10, 2015. https://www.dezeen.com/2015/07/30/san-cataldo-cemetery-modena-italy-aldo-rossi-postmodernism/.

10. Ghirardo, Diane. Aldo Rossi and the Spirit of Architecture (Yale University Press, 2019), 170.

11. Klotz, Heinrich. Postmodern Visions: Drawings, Paintings, and Models by Contemporary Architects. (New York: Abbeville Press, 1985), 233.

12. Klotz, 9.

13. Klotz, 234.

14. Klotz, 234.

15. Klotz, 234.

16. Ferlenga, Alberto. Aldo Rossi, Architecture, 1959-1987. (Milan: Electa Moniteur, 1988), 60.

17. Klotz, 234.

18. Klotz, 234.

19. Klotz, 234.

20. Goldberger, Paul. "Architecture View; Aldo Rossi: Sentiment For The Unsentimental." New York Times, Apr 22, 1990, Late Edition (East Coast).

21. Lopez, T. M. (2017). The future city. Southwest Review, 102(1), 101,151. Retrieved from https://proxy.library.mcgill.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1890523429?accountid=12339

22. Mairs, Jessica.

23. Malone, Hannah. Architecture, Death And Nationhood: Monumental Cemeteries of Nineteenth-century Italy. (Routledge, 2018), 14.

24. Collier, C. D. Abby. "Tradition, Modernity, and Postmodernity in Symbolism of Death." The Sociological Quarterly 44, no. 4 (2003): 735. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2003.tb00533.x.

25. Collier, C. D. Abby. "Tradition, Modernity, and Postmodernity in Symbolism of Death." The Sociological Quarterly 44, no. 4 (2003): 738. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2003.tb00533.x.

26. Malone, Architecture, Death And Nationhood, 15.

27. "San Cataldo Cemetery in Modena, Italy." Act of Traveling. Accessed March 30, 2019. https://www.actoftraveling.com/portfolio/san-cataldo-cemetery-modena-italy/.

28. Storeganizer. "Solutions for Warehouse Storage." Storeganizer. Accessed March 30, 2019. https://www.storeganizer.com/us/solutions/.

29. "San Cataldo Cemetery in Modena, Italy." Act of Traveling. Accessed March 30, 2019. https://www.actoftraveling.com/portfolio/san-cataldo-cemetery-modena-italy/.

30. "Warehousing & Storage." Warehousing and Storage | Crown International Pack and Move. Accessed March 30, 2019. http://crownintpackers.com/warehousing-storage.html.

31. Ghirardo, Diane. Aldo Rossi and the Spirit of Architecture. (Yale University Press, 2019), 4.

32. Malone, Hannah. "Legacies of Fascism: Architecture, Heritage and Memory in Contemporary Italy." Modern Italy22, no. 04 (2017): 448. doi:10.1017/mit.2017.51.

33. Ghirardo, 172.

34. Lopez, T. M. (2017). The future city. Southwest Review, 102(1), 101,151. Retrieved from https://proxy.library.mcgill.ca/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/1890523429?accountid=12339

35. Lopez, 101.

36. Klotz, , 236.

37. Klotz, Heinrich. Postmodern Visions: Drawings, Paintings, and Models by Contemporary Architects. (New York: Abbeville Press, 1985), 234.

38. Ghirardo, Aldo Rossi and the Spirit, 170.

39. Klotz, Postmodern Visions, 234.